Iraq Premier-Designate Has His Work Cut Out For Him

By Shashank Bengali and Brian Bennett, Tribune Washington Bureau

WASHINGTON — Early in 2007, with Iraq embroiled in sectarian violence, American diplomats in Baghdad tried to persuade a key Shiite Muslim lawmaker to support the easing of a ban on the Sunni Arab-dominated Baath Party.

At a meeting at the U.S. Embassy, the lawmaker, Haider al-Abadi, was noncommittal, saying that changes to the laws forbidding political activity by Saddam Hussein’s old party would be a tough sell with Shiites. But al-Abadi, a British-educated engineer, also expressed hope that the rival sects would find common ground in opposition to Sunni-led al-Qaida extremists.

Sunni lawmakers “are looking for allies,” al-Abadi said, according to a State Department dispatch obtained by the anti-secrecy website WikiLeaks. “We are ready.”

That encounter was quintessential al-Abadi, according to former U.S. officials and analysts who have followed the career of the man who was tapped this week to serve as Iraq’s next prime minister.

Seen as less ideological and more moderate than many leading Shiite politicians — including the man he would replace, divisive two-term Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki — he is at the same time a cautious party man who has rarely broken with the Shiite mainstream on crucial issues such as “de-Baathification” and power sharing.

With the United States now seeking to reverse the momentum of the Islamic State, an al-Qaida breakaway group that has swept across northern and western Iraq, Obama administration officials hope that al-Abadi will make good on previous overtures toward minority Sunni Arabs and Kurds and form a more inclusive, moderate government. As a former businessman and chairman of the parliament’s finance committee, he earned a reputation for pragmatism and support of private enterprise.

“Abadi is known in Iraq as someone who can reach across the party aisle and has earned respect as a skilled negotiator,” said a U.S. official who spoke on condition of anonymity in discussing internal assessments.

Yet even if al-Abadi is able to form a ruling coalition, he may still struggle to win the crucial support of Sunnis, whose disaffection with al-Maliki’s sectarian policies has fueled the rise of the Sunni extremists. Al-Abadi secured the prime ministerial nomination Monday with the backing of a Shiite coalition that includes supporters of former Oil Minister Hussein Shahristani, who has angered Sunni Arabs and Kurds by insisting that all Iraqi oil be controlled by the Shiite-led central government, and the radical cleric Muqtada al-Sadr.

“Neither he nor his coalition are auspicious in terms of expecting a significant change,” said Kirk Sowell, a political analyst who edits the Inside Iraqi Politics newsletter and is based in Jordan.

“There were people around Maliki who were flamethrowers; (Abadi is) not a flamethrower. But at the same time, Abadi has never been known as someone who’s pushing reforms.”

On Wednesday, al-Maliki said in a weekly televised address that he would not give up power until Iraq’s high court rules on his claim to office, but he pledged not to use force to keep his post. With support for al-Maliki evaporating, al-Abadi is moving ahead with forming a new Cabinet under a constitutionally mandated 30-day deadline.

Like al-Maliki, the Baghdad-born al-Abadi is a longtime member of the Islamic Dawa Party, a Shiite opposition group banned during Saddam’s long rule. But the two men took different paths as exiles pushing for the dictator’s overthrow.

In the 1980s, while al-Maliki took part in clandestine efforts from Syria and Iran to destabilize the Baathist-led government, al-Abadi lived in Britain, where he earned a doctorate in engineering from the University of Manchester. According to a biography on his Facebook page, two of his brothers were executed in Iraq in 1982 for being Dawa members.

Al-Abadi remained with his family in Britain and ran a small company that, among other things, helped to modernize London’s transportation system. He returned to Baghdad in 2003 after the U.S.-led invasion that toppled Saddam and became minister of communications in the Coalition Provisional Authority under American civilian administrator L. Paul Bremer III. Al-Abadi was elected to Iraq’s re-formed parliament in 2006.

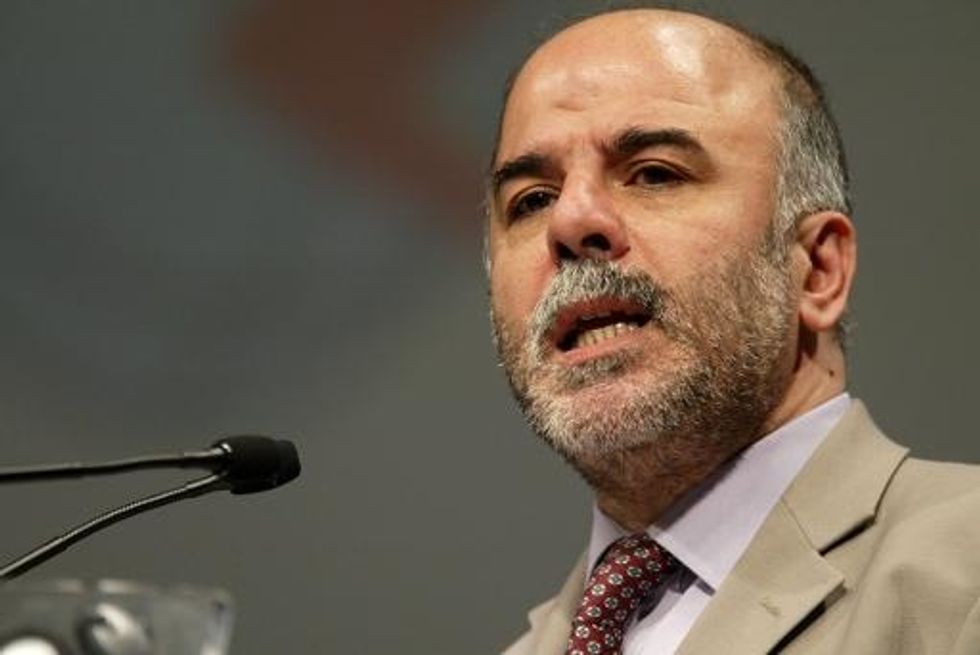

Balding, with a neatly trimmed gray beard, al-Abadi is better known to Iraqis than al-Maliki was when U.S. officials plucked the latter from obscurity and backed him for the premiership. American diplomats who have since worked behind the scenes for al-Maliki’s ouster believe al-Abadi may be more open-minded toward Washington and other Western allies, officials said.

Before the Obama administration launched airstrikes last week against Islamic State militants in northern Iraq, al-Abadi was a vocal proponent of U.S. military intervention. He told the Huffington Post in June that renewed U.S. involvement would mean the Iraqi government would not have to rely solely on military support from Iran.

“There are some reasons to think he is not beholden to or enamored with Iran as Maliki has been,” said David Pollock, a Middle East expert at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy.

In the same interview, al-Abadi acknowledged that Iraqi security forces had committed “excesses” that should be investigated, without elaborating. Under al-Maliki, the security forces were accused of abducting and torturing untold numbers of civilians, most of them Sunnis, who were being held without charges.

But al-Abadi rejected allegations that al-Maliki persecuted or marginalized Sunnis. He has also drawn the ire of Kurds for saying their demands for a greater share of oil revenue from the semiautonomous northern Kurdish region could cause Iraq’s “disintegration.”

Experts say that as prime minister, al-Abadi would have to take swift steps to reform Iraq’s security establishment and share sufficient power with Sunni Arabs and Kurds to build support for fighting the Islamist militants.

“He’s going to face every single challenge that Maliki faced,” said Hayder al-Khoei, an Iraq expert at Chatham House, a British-based think tank. “That has nothing to do with personalities. There are systematic failures having to do with governance, nepotism, corruption that are not going to go away overnight.”

Bengali reported from Mumbai, India, and Bennett from Washington.

AFP Photo/Jean-Philippe Ksiazek

Interested in world news? Sign up for our daily email newsletter!