Reprinted with permission from TomDispatch

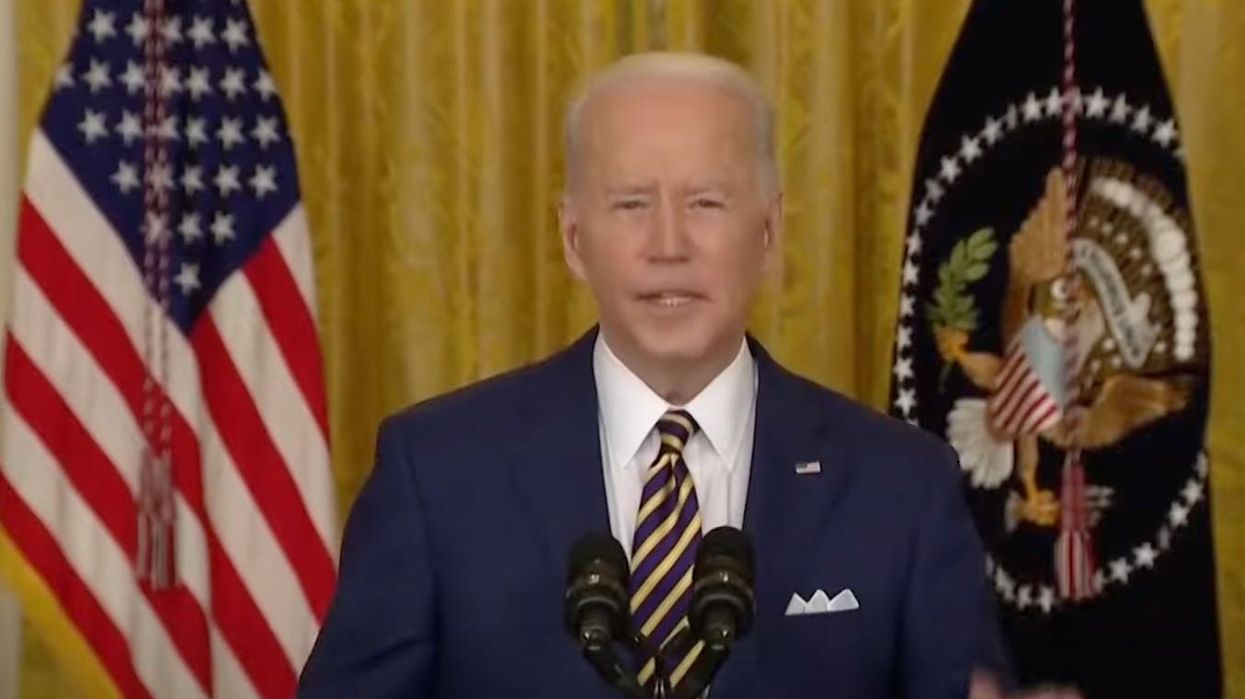

It ended in chaos and disaster. Kabul has fallen and Joe Biden is being blamed (by congressional Republicans in particular) for America's now almost-20-year disaster in Afghanistan. But is the war on terror itself over? Apparently not.

It seems like centuries ago, but do you remember when, in May 2003, President George W. Bush declared "Mission accomplished" as he spoke proudly of his invasion of Iraq? Three months later, Attorney General John Ashcroft proclaimed, "We are winning the war on terror." Despite such declarations and the "corners" endlessly turned as America's military commanders announced impending successes year after year in places like Afghanistan and Iraq, the war on terror, abroad and on the home front, has been never-ending, as the now-codified term "forever wars" suggests.

By 2011, following the death of Osama bin Laden, President Barack Obama admitted that the killing of the head of al-Qaeda would not bring that war to a close. In May 2011, he informed the nation that bin Laden's "death does not mark the end of our effort" as "the cause of securing our country is not complete." As President Biden signals his intention to bring the war on terror as we know it to an end, the question is: What will remain of it both abroad and at home, no matter what he tries to do?

The Pivot Abroad

As the 20th anniversary of the 9/11 attacks looms, the Biden administration is making it crystal clear that it intends to finally bring the most obvious aspects of that war to a close, no matter the consequences. "It is time," Biden, the fourth war-on-terror president, said in April, "to end the Forever War." Although mired in controversy, turmoil, and bloodshed, the withdrawal of American troops from Afghanistan did indeed take place, even if several thousand were then sent back to Kabul Airport to guard the panicky removal of the vast American embassy staff and others from that city. That was, as the administration announced, only a temporary measure as Taliban troops entered the Afghan capital and took over the government there.

Eighteen years after the invasion of Iraq, a shifting definition of the role of the 2,500 or so U.S. troops still stationed there is also underway and should be complete by the end of the year. Instead of more combat missions, the American role will now be logistics and advisory support.

Putting a fine point on both the Afghan withdrawal and the Iraqi change of direction, many in Congress have acknowledged the need to remove the authorizations passed so long ago for those forever wars. In June, the House of Representatives voted to repeal the 2002 Authorization for the Use of Force (AUMF) in Iraq that paved the way for the invasion of that country. And this month, the Senate Foreign Relations Committee followed suit — 18 years after George W. Bush deposed Iraqi autocrat Saddam Hussein and disaster followed.

The removal of that 2002 AUMF remains, of course, painfully overdue. After all, it has been used through these many years to cover this country's disastrous occupation of and attempts at "nation-building" in Iraq. Eventually, during Donald Trump's last year in office, it was even cited to authorize the drone assassination of a top Iranian general at Baghdad International Airport. Like so many war-on-terror policies, once put in place, successive administrations showed no urge to let that AUMF go. In that way, what had once been a regime-change directive (based on a set of lies about weapons of mass destruction in Saddam Hussein's Iraq) morphed into a long-term nation-building scheme, without any new congressional authorizations at all.

Plans are also now on the table for the repeal of the even more impactful 2001AUMF, passed by Congress one week after 9/11. Like the Iraq War authorization, its use has been expanded in ways well beyond its original intent — namely, the rooting out of Osama bin Laden and al-Qaeda in Afghanistan. Under the 2001 AUMF's auspices, in the last nearly two decades, the United States has conducted military operations in ever more countries across the Greater Middle East and Africa. But in Congress, what's now being discussed is not just repealing that act, but replacing it altogether.

Traditionally, when a war ends, there's a resolution, perhaps codified in a treaty or an agreement of some sort acknowledging victory or defeat, and a nod to the peace that will follow. Not so with this war.

However unsuccessful, the war on terror, experts tell us, will instead continue. The only difference: it won't be called a war anymore. Instead, there will be a variety of militarized counterterrorism efforts around the globe. With or without the moniker of "war," the U.S. remains at war in numerous places, only recently, for instance, launching airstrikes on Somalia to counter the terrorist group al-Shabaab.

In Africa, Syria, and Indonesia, experts warn, the continued spread of ISIS, the reinvigoration of al-Qaeda, and the persistence of groups like Jemaah Islamiyah demand a continued American military counterterrorism effort. All of this was, in a strange way, foreseeable in the drafting of the 2001 AUMF in which no enemy was actually named, nor were temporal or geographical limits or conditions laid down for the resolution of the conflict to come. As the war on terror's spread to country after country has demonstrated, once unleashed, such a war paradigm takes on a life of its own.

After 20 years of various kinds of failure in which the goals of the war on terror were never truly attained, the U.S. military, the intelligence community, and the Biden administration are now focused elsewhere. According to the latest government threat assessment issued in April by the Director of National Intelligence (DNI), terrorism is far from the most serious threat the nation faces today. As Emily Harding of the Center for Strategic and International Studies sums it up, reflecting on the DNI's report, the intelligence community's priorities "are shifting… from a focus on counterterrorism to addressing near-peer competitors."

"The United States is transitioning," Harding explains, "from mostly low-tech, low-resourced adversaries (e.g., the Islamic State, al-Qaeda, and their subsidiaries) to a focus on great power competition, in particular with China and Russia, both of whom have invested in sophisticated technical tools and are armed with robust conventional and nuclear forces."

Still, however much the Biden administration may be pivoting to a new cold war with China in particular, just how long such a pivot lasts remains an open question, especially given the recent Afghan disaster. And despite the coming 20th anniversary of 9/11, no matter what Congress does or doesn't rescind when it comes to those AUMFs, the U.S. forever war with terrorism will persist, even if, for a while, the threat of Islamic terrorism takes a back seat to other potential dangers in official Washington.

The Pivot At Home

On the home front, there's a similarly disturbing persistence when it comes to the war on terror. Like that set of conflicts abroad, counterterrorism efforts against Islamist terrorists at home have given way to other issues. Mirroring the reduced importance of international terrorism in the report of the director of national intelligence, for instance, Attorney General Merrick Garland recently highlighted a domestic shift away from Islamic terrorism in a memorandum to Department of Justice (DOJ) personnel.

Outlining the "broad scope" of the department's responsibilities, his priorities couldn't have been clearer. His first commitment, he insisted, was to restoring the integrity of the department, a clear reference to the DOJ's rejection of independence from the White House during the Trump years. Meanwhile, he explained, the Justice Department will focus on its primary mission — protecting Americans "from environmental degradation and the abuse of market power, from fraud and corruption, from violent crime and cyber-crime, and from drug trafficking and child exploitation." Only as a seeming afterthought did he add, "And it must do all of this without ever taking its eye off of the risk of another devastating attack by foreign terrorists."

But his words hid a more subtle reality. Much of the domestic architecture created in the name of the war on terror persists at home as well as abroad. At its height, the counterterrorism movement at home involved an expansive and aggressive use of law enforcement and intelligence tools that readily — often with the assent of Congress and the courts — tossed aside constitutional protections and reinterpreted laws in ways that privileged American security over rights.

Passed in October 2001, the Patriot Act, for example, downgraded Fourth Amendment protections, enabling law enforcement to conduct mass warrantless surveillance on Americans. Muslims as a group — rather than based on individual suspicion — were detained without charge, targeted in stings and terror investigations, and threatened with imprisonment at Guantanamo Bay.

During President Obama's term in office, some of these measures were revised for the better in the Freedom Act. Meant to replace the Patriot Act, while leaving many broad authorities in place, it banned the bulk intelligence collection of American telephone records and Internet metadata. For the most part, however, law enforcement's counterterrorism powers, created to defeat al-Qaeda, have remained robust and are there for use against others.

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS), created in the wake of 9/11, has also turned its attention elsewhere. Almost from its inception, the agency used the powers granted to it in the name of counterterrorism in other ways entirely. It soon turned its attention to dealing with drug crimes, the control of the border, and immigration matters, all outside the realm of post-9/11 terrorist threats.

Under President Trump, in particular, DHS (by then, remarkably enough, the country's largest law enforcement agency) refocused its resources on matters that had little or nothing to do with counterterrorism. During the Black Lives Matter protests in the summer of 2020, for instance, its officials deployed helicopters, drones, and other forms of group surveillance to monitor protests and, in Portland, Oregon, even to quell them with force. In other words, the agency built for counterterrorism had, by then, become whatever a president wanted it to be.

A Call For Review

The future of such powers and policies at home and abroad is now in a strange kind of limbo. Addressing the Trump administration's misuse of the Department of Justice, for instance, Attorney General Garland did indeed signal his intent to limit any use of it for political purposes. In the process, he issued a clear directive against any possible White House politicization of the department. But not a mention has yet been made of authorizing a much-needed thorough review of the powers the DOJ gained in the forever-war years in the name of counterterrorism.

When it comes to the Department of Homeland Security, the path to reform is even less clear as, in its repurposed mission, counterterrorism aimed at foreign groups may be among the least of its tasks. As a recent report from the Center for American Progress points out, "What America needs from DHS today… is different from when it was founded… [W]e need a DHS that prioritizes the rule of law, and one that protects all Americans as well as everyone who comes to live, study, work, travel, and seek safety here."

In fact, in these years, both at home and abroad, counterterrorism agencies and the military were granted vast new powers. While they may now all be pivoting elsewhere in the name of new threats, they are certainly not focused on limiting those powers in any significant way.

And yet such limits couldn't be more important. It would, in fact, be wise for this country to pause, review the uses of the post-9/11 powers granted to such domestic institutions, and revise the policies that allowed for their seemingly endless expansion at home and abroad in the name of the war on terror. It would be no less wise to place more confidence in the country's ability to keep itself safe by embracing its foundational principles. At home, that would mean honoring fairness and restraint in the application of the law, while insisting on limits to the use of force abroad.

If only.

At present, it looks as if those forever wars have created a new form of forever law, forever policy, forever power, and a forever-changed America. And count on one thing: if changes aren't made, we in this country will find ourselves living forever in the shadow of those forever wars.

Karen J. Greenberg, a TomDispatch regular, is the director of the Center on National Security at Fordham Law and author of the newly published Subtle Tools: The Dismantling of Democracy from the War on Terror to Donald Trump (Princeton University Press). Julia Tedesco helped with research for this piece.