Speaker Johnson's Strange Manipulation Of His Shadowy 'Black Son'

“Some of my best friends are Black” is a phrase that has become cliché, and deservedly so, since it is essentially a dodge. Folks uttering those words are looking for a free pass, credit for knowing what it means to be Black in America without doing the work.

By now, most people know that proximity does not equal understanding.

Most, but not all.

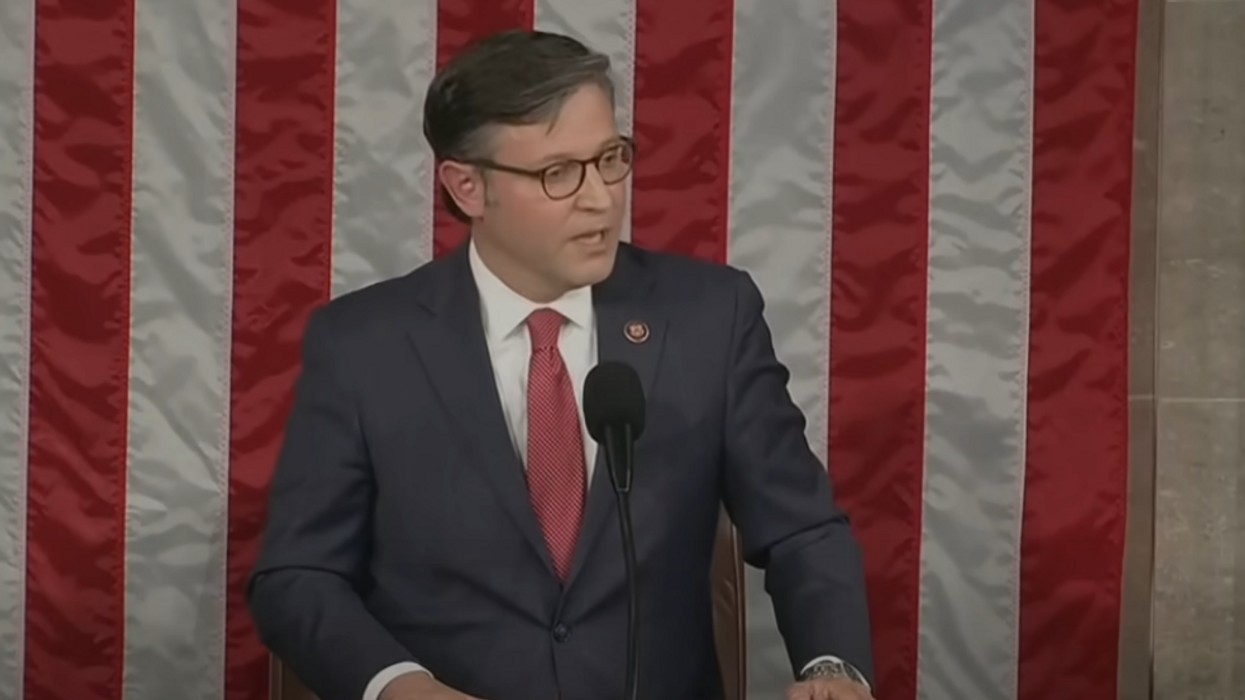

The new speaker of the House, GOP Rep. Mike Johnson of Louisiana, has been known to showcase the Black child in his family’s life over two decades, usually when his empathy on matters of race needs a boost. Johnson controls the narrative. He doesn’t want to infringe on the privacy of a now-grown man with a family, he says, so he won’t go into too much detail.

Just enough, though, to show he gets it.

I have nothing against any person of any race who wants to foster, mentor or teach any young person in need of guidance. I applaud the realization that all parties on both sides of such relationships have opportunities to learn and grow. At the same time, I think it’s fair that reporters question just how formal the relationship between congressman and child has been, and why this child is conspicuously missing from family biographies and photographs.

I also wonder about any story cut from the same cloth as The Blind Side, the simple tale of a wealthy white family “adopting” a deprived Black child, rescuing him from an ignoble fate and smoothing his way to football glory in college and the pros. That “just like a movie” story, which has been cited by Johnson as a template, was far more complicated, as the world has come to learn.

Johnson’s tale seems to be similar in many ways, with one particular problem common to these kinds of inspirational parables. They almost always place the white benefactor front and center, instead of the person who was a person before being molded by a Good Samaritan.

In the case of popular movie The Blind Side, a young Michael Oher was already a gifted, smart and hard-working young man and athlete with admirable Black role models, not the nearly mute cipher portrayed as a vessel for the Tuohy family’s largesse in an Oscar-winning film. Oher, in his own voice, said as much in books and when he took his “family” to court to sever a conservatorship that was never an adoption.

I don’t know much about Johnson’s ward, son, or however he would describe the man, also named Michael, except what I’ve learned when he makes a cameo appearance in a pithy yarn from the new speaker.

Reparations? Johnson is against awarding any kind of compensation to descendants of those discriminated against, locked out of an equal shot at the American dream for generations. He came to the conclusion not after a close examination of American history. No, rather than depending on the facts of the case, attorney-turned-lawmaker Johnson relied on Michael, who, he told a House subcommittee, thought reparations defied an “important tradition of self-reliance.”

Funny, I don’t know what the Johnsons’ four biological children think about reparations, or anything else.

After George Floyd was murdered, Johnson acknowledged the existence of a world that treated his two then 14-year-olds differently. Johnson said on PBS: “Michael being a Black American and Jack being white Caucasian. They have different challenges. My son Jack has an easier path. He just does.”

But that was so 2020. Since his recent promotion, to assuage a MAGA base who believes such talk makes him an “undercover Democrat,” as one conservative activist has put it, Johnson told Fox News’ Sean Hannity it wasn’t race so much as “culture and society,” that was the culprit, “a really troubled background” and “a lot of challenges.”

Seems like Johnson, while shielding the child who’s like a member of his family, doesn’t mind squeezing him into the most stereotypical The Blind Side frame, speaking for and about him.

Pretty much everyone could have seen that coming from a politician with Johnson’s mix of piety, judgment, and ambition.

It’s pretty rich that Johnson downplayed the role of systemic racism as he represented a state that in the past spawned the U.S. Supreme Court disgrace of Plessy v. Ferguson’s “separate but equal” doctrine, and is now in court disputes on congressional districts that give African American voters a fair chance.

Where does Johnson stand on banning books that teach his son or any other child these Louisiana truths? Maybe we’ll soon hear from Johnson that “Michael” disapproves.

If Mike Johnson really wanted to know what African Americans feel, about anything, he could reach out to his constituents in the state’s Fourth District, which is about one-third Black.

In talking with residents of the Shreveport-Bossier area, The Washington Post and The New York Times found stark divides along party and race, which often walk together in the South, though no race is monolithic in opinion. Many white conservatives, including his mom, were quoted as loving Johnson’s agenda, and believing a spiritual hand more than an exhausted Republican House caucus eased his elevation to speaker.

Instead of listening only to that choir and the Black child who, in his telling, whispers in his ear on racial issues, Johnson should consider consulting dissenting constituents who tell him things he may not want to hear. Those citizens have far more experience raising Black children in a state and district with a history of racial discrimination in education, housing, employment, voting rights, criminal justice and so much more.

In showing humility and doing the work he was sent to Washington to do, Johnson might learn something — and finally give Michael that privacy.

Reprinted with permission from Roll Call.