By Alan Zarembo, Los Angeles Times (TNS)

As a young psychiatry resident at Ohio’s Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in the 1980s, Dr. George Brown was surprised the first time he saw a transgender patient.

Estimates at the time were that for every 100,000 biological males in the general population, no more than three were transgender.

Brown figured the rate had to be even lower in the all-volunteer military. It made little sense to him that a transgender person would choose to join an institution that by its nature had no tolerance for deviance.

Yet over the next three years, Brown saw 10 more transgender patients — all of them seeking hormone therapy and male-to-female gender reassignment surgery. He began to suspect that the military, despite its ban on allowing transgender people to serve, was somehow attracting them at a disproportionately high rate.

The Pentagon is now weighing whether to lift its ban on transgender service members and is expected to do so next year. As the policy is reviewed, researchers are citing evidence that bears out Brown’s hunch of three decades go.

Transgender people are present in the armed services at a higher rate than in the general population.

The latest analysis, published last year by UCLA researchers, estimated that nearly 150,000 transgender people have served in the military, or about 21 percent of all transgender adults in the U.S. By comparison, 10 percent of the general population has served.

The findings have pumped new life into a theory that Brown developed to explain what he had witnessed. In a 1988 paper, he coined it “flight into hypermasculinity.”

His transgender patients told him that they had signed up for service when they were still in denial about their true selves and were trying to prove they were “real men.”

“I just kept hearing the same story over and over again,” said Brown, 58, now a professor at East Tennessee State University and a specialist in gender identity issues at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Mountain Home, Tenn.

Some patients had deliberately chosen the military’s most dangerous jobs. In one case described in the paper, a 37-year-old patient with a long history of cross-dressing had been a laboratory technician on a base in Germany but gave that up to become a combat helicopter pilot at the height of the Vietnam War, a job with a high death rate.

Colene Simmons, 60, says she is one of Brown’s longtime patients. She started life in rural Georgia as O’Day Simmons. A 185-pound champion wrestler in high school, Simmons protected other students from bullies and had no problem getting girlfriends.

But the tough exterior belied inner fantasies.

Simmons had escaped a physically abusive father and grown up in a Christian group home.

“God doesn’t make mistakes,” the house mother said after discovering Simmons trying on a curtain as if it were a dress.

As the demons grew stronger, Simmons enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps in the hope of fighting them off. “I wanted to prove to myself that I was a man,” she explained.

Stationed at Camp Geiger, N.C., in the late 1970s, Simmons occasionally left the base and drove 80 miles to a thrift store to buy women’s clothes and check into a motel room alone to play dress-up.

Simmons later married and had two children, but that could not erase her feelings any more than spending four years in the military.

She eventually underwent hormone therapy and surgery and legally changed her name. Remarried to another woman, she considers herself a lesbian. They live in rural northeast Tennessee.

“Colene doesn’t talk much about the military,” said Jane Simmons, her wife.

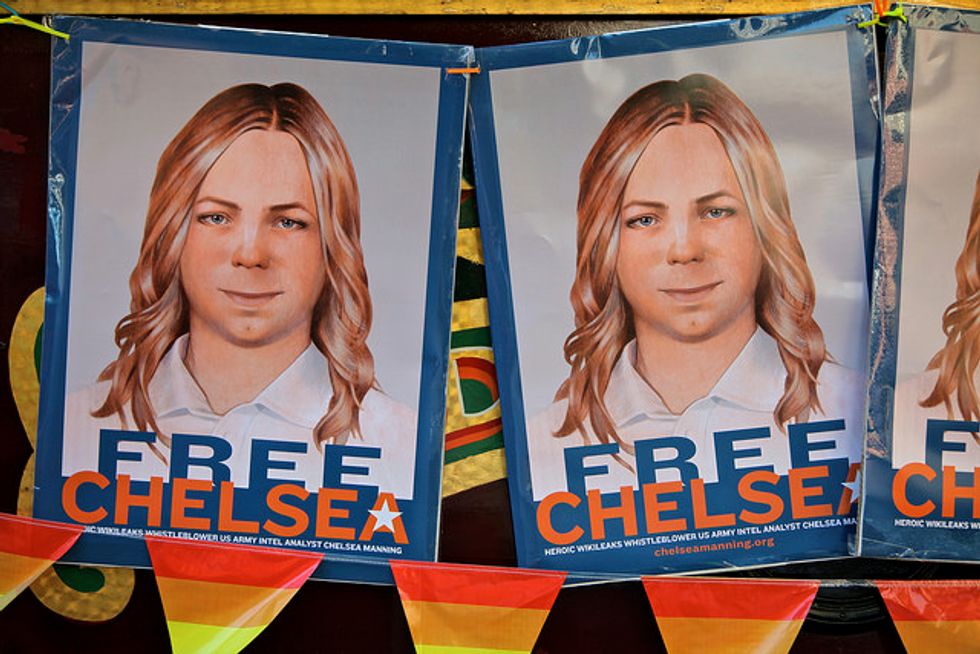

For all the attention gender identity has received recently — including Olympian Bruce Jenner’s transformation to Caitlyn Jenner and Army Pvt. Bradley Manning’s emergence as Chelsea Manning after being convicted of leaking classified documents — even the size of the transgender population is open to wide speculation.

The U.S. Census Bureau does not collect data to determine it, so researchers must extrapolate from other, smaller surveys.

In 2011, Gary Gates, research director at UCLA’s Williams Institute, which is devoted to public policy questions related to gender identity and sexual orientation, estimated that 3 of every 1,000 U.S. adults are transgender — at least 100 times the presumed rate in the 1980s.

Figuring out how many transgender people serve in the military is even harder, because they can be kicked out if they reveal themselves.

“We’re working largely in a vacuum,” Gates said.

His estimates are based on demographic tweaks to the results of a 2008 nationwide survey of more than 6,500 transgender people that was conducted by activist groups.

Among those assigned male at birth, Gates found that 32 percent had served in the military, compared with 20 percent of men in the general population who had served.

For those assigned female at birth, that figure was 5.5 percent, compared with 1.7 percent of all women.

Other measures suggest even bigger differences between transgender people and the rest of the population in terms of military service.

In 2011, nearly 23 out of every 100,000 patients in the VA system had a diagnosis of gender identity disorder, which is used to describe gender identity issues that lead to significant levels of psychological distress and has been associated with high suicide risk.

That’s five times the rate in the general population.

The comparison comes with a caveat. In 2011, the VA began providing hormone therapy and other nonsurgical treatment for transgender patients, a strong motivation for some people to seek a diagnosis.

Though Brown developed his theory around male-to-female transgender service members, the draw of a hypermasculine environment may also help explain why female-to-male transgender people join the military.

The theory has been a topic of debate among activists and researchers. Although most say it has validity, some worry that its simplicity undermines the full humanity of transgender people.

“It dehumanizes the community and reduces it to this narrative,” said Jake Eleazer, a transgender veteran and doctoral student in psychology at the University of Louisville in Kentucky.

He and others point out that there are many reasons transgender people join the military: adventure, money for college, family tradition and other factors that attract all recruits.

They also say it is possible that transgender people are more likely to have certain traits or skills that draw them to service, or that on the whole they are socio-economically disadvantaged, discriminated against or rejected by their families in a way that leaves them fewer other options.

But there is not enough data to test those ideas.

Whatever the reasons that transgender people join, their presence has become one of the government’s most powerful arguments for lifting the ban.

“Transgender men and women in uniform have been there with us, even as they often had to serve in silence alongside their fellow comrades in arms,” Defense Secretary Ashton Carter said in a July statement announcing that the Pentagon would review the ban starting with the premise that it should be rescinded.

Brown predicted that even if the ban is lifted, the military will continue to attract transgender 18- to 20-year-olds who have yet to come to terms with their true selves.

As a place to hide, consciously or subconsciously, the military, with its order and uniformity and prohibitions on self-expression, may be unrivaled.

Jennifer Long, who joined the Army in 1983 as Edward Long, managed to suppress her feminine identity for her first 22 years of duty as a drill sergeant, paratrooper and security official at the detention camp at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba.

“You’re in very gender binary roles,” she said. “It doesn’t leave any room. There’s no gray area.”

Eventually, though, she could no longer run from herself. After a second divorce in 2005, Long attempted suicide.

“You want to make it all go away,” she said. “You can’t be who you want to be.”

Then Long started meeting other transgender people online and dressing as a woman off-duty in the evenings and on the weekends.

After a deployment to Iraq in 2008, she began taking hormones with plans to leave the military and live openly as a woman. A combat duty assignment in Afghanistan delayed her retirement until 2012.

Now 50, Long lives in New Jersey and works as a financial adviser.

“If I could have remained on duty, I would have,” she said.

Photo: Chelsea Manning is one of many male-to-female transgender adults who have served in the military. Many have said they joined the military to be in a hypermasuline environment — but it did not stem their feminine urges. torbakhopper/Flickr