Sometimes, Race Is More Distraction Than Explanation

Dear white people:

As you no doubt know, the water crisis in Flint, Mich., returned to the headlines last week with news that the state attorney general is charging three government officials for their alleged roles in the debacle. It makes this a convenient moment to deal with something that has irked me about the way this disaster is framed.

Namely, the fact that people who look like you often get left out of it.

Consider some of the headlines:

The Racist Roots of Flint’s Water Crisis — Huffington Post

How A Racist System Has Poisoned The Water in Flint — The Root

A Question of Environmental Racism — The New York Times

As has been reported repeatedly, Flint is a majority black city with a 41 percent poverty rate, so critics ask if the water would have been so blithely poisoned, and if it would have taken media so long to notice, had the victims been mostly white.

It’s a sensible question, but whenever I hear it, I engage in a little thought experiment. I try to imagine what happened in Flint happening in Bowie, a city in Maryland where blacks outnumber whites, but the median household income is more than $100,000 a year and the poverty rate is about 3 percent. I can’t.

Then I try to imagine it happening in Morgantown, West Virginia, where whites outnumber blacks, the median household income is about $32,000 a year, and the poverty rate approaches 40 percent — and I find that I easily can. It helps that Bowie is a few minutes from Washington, D.C., while Morgantown is more than an hour from the nearest city of any size.

My point is neither that race carries no weight nor that it had no impact on what happened in Flint. No, my point is only that sometimes, race is more distraction than explanation. Indeed, that’s the story of our lives.

To be white in America is to have been sold a bill of goods that there exists between you and people of color a gap of morality, behavior, intelligence and fundamental humanity. Forces of money and power have often used that perceived gap to con people like you into acting against their own self-interest.

In the Civil War, white men too poor to own slaves died in grotesque numbers to protect the “right” of a few plutocrats to continue that despicable practice. In the Industrial Revolution, white workers agitating for a living wage were kept in line by the threat that their jobs would be given to “Negroes.” In the Depression, white families mired in poverty were mollified by signs reading “Whites Only.”

You have to wonder what would happen if white people — particularly, those of modest means — ever saw that gap for the fiction it is? What if they ever realized you don’t need common color to reach common ground? What if all of us were less reflexive in using race as our prism, just because it’s handy?

You see, for as much as Flint is a story about how we treat people of color, it is also — I would say more so — a story about how we treat the poor, the way we render them invisible. That was also the story of Hurricane Katrina. Remember news media’s shock at discovering there were Americans too poor to escape a killer storm?

Granted, there is a discussion to be had about how poverty is constructed in this country; the black poverty rate is higher than any other with the exception of Native Americans, and that’s no coincidence. But it’s equally true that, once you are poor, the array of slights and indignities to which you are subjected is remarkably consistent across that racial gap.

That fact should induce you — and all of us — to reconsider the de facto primacy we assign this arbitrary marker of identity. After all, 37 percent of the people in Flint are white.

But that’s done nothing to make their water clean.

(Leonard Pitts is a columnist for The Miami Herald, 1 Herald Plaza, Miami, Fla., 33132. Readers may contact him via e-mail at lpitts@miamiherald.com.)

(c) 2016 THE MIAMI HERALD DISTRIBUTED BY TRIBUNE CONTENT AGENCY, LLC.

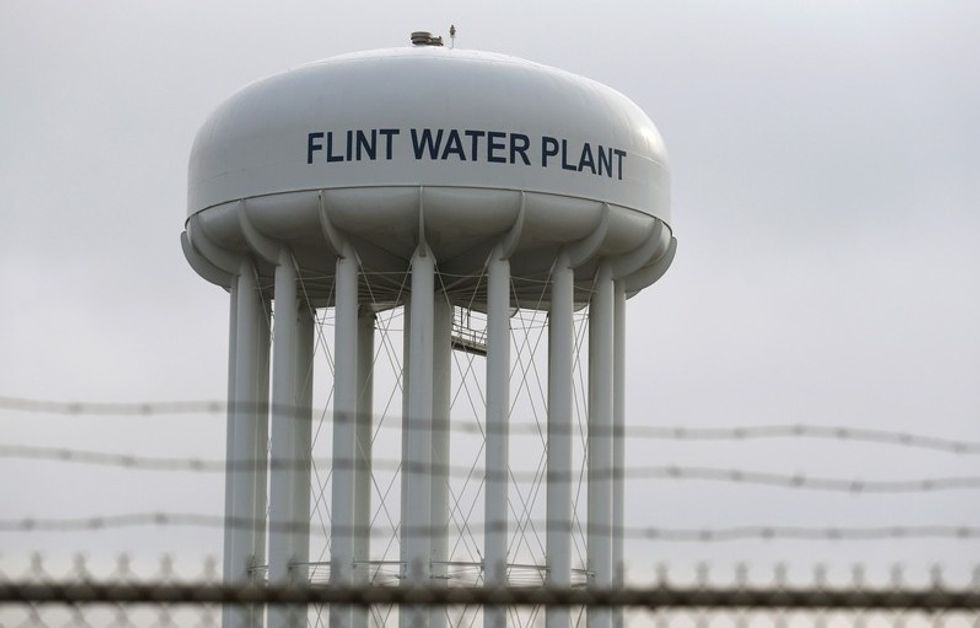

Photo: The top of the Flint Water Plant tower is seen in Flint, Michigan in this February 7, 2016 file photo. REUTERS/Rebecca Cook/Files