Oklahoma Report Blames Intravenous-Line Woes For Problematic Execution

By Michael Muskal, Los Angeles Times

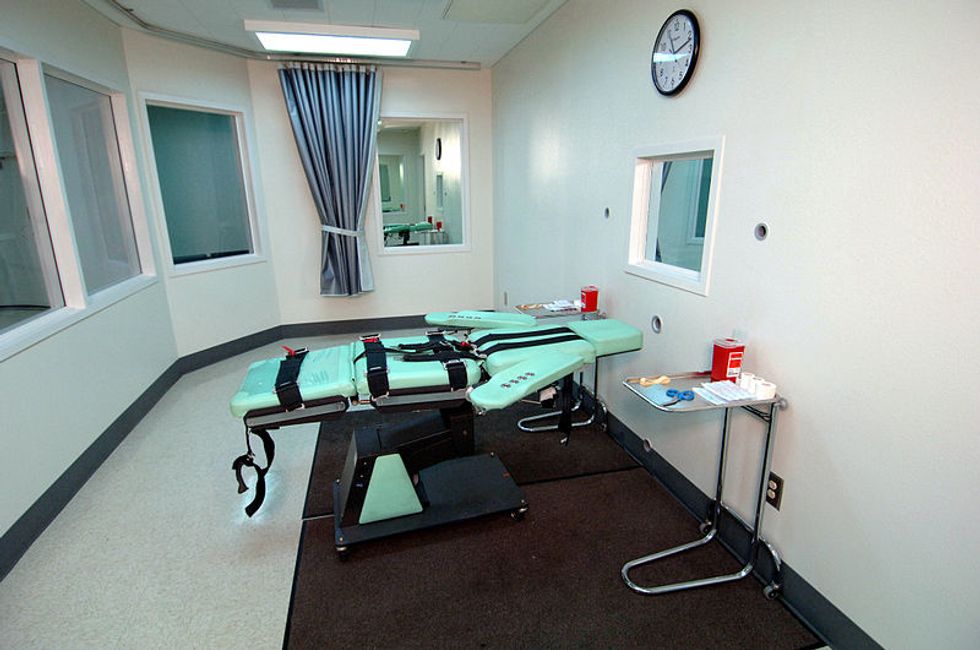

Problems with using and monitoring an intravenous line carrying a deadly cocktail of drugs were responsible for the lengthy execution of Clayton Lockett in Oklahoma, according to a state report that recommended some changes but found that corrections officials had substantially complied with existing protocols for capital punishment.

The report prepared by the Oklahoma Department of Public Safety noted that medical personnel were forced to insert the IV line, carrying the execution drugs, into a vein in Lockett’s groin after failing to find a viable vein in the more usual places such as legs or arms. The IV site was covered with a sheet and not monitored until the physician saw swelling larger than a golf ball, the report released online Thursday said.

“The physician and paramedic made several attempts to start a viable IV access point. They both believed the IV access was the major issue with this execution. This investigation concluded the viability of the IV access point was the single greatest factor that contributed to the difficulty in administering the execution drugs,” according to the report.

The report called for some changes including making the IV site visible to officials throughout an execution, better training for contingencies during an execution, and making additional supplies available during an execution. Overall, however, the report says officials acted properly during the April 29 execution of Lockett even though it took 43 minutes for him to die and he was said by witnesses to be writhing in pain.

“Regarding whether DOC correctly followed their current execution protocols, it was determined there were minor deviations from specific requirements outlined in the protocol in effect on April 29,” according to the report. “Despite those deviations, it was determined the protocol was substantially and correctly complied with throughout the entire process. None of the identified deviations contributed to the complications encountered during this execution.”

The report was the result of an investigation ordered by state officials into Lockett’s execution, one of several executions that raised questions about how states administer the death penalty without violating Constitutional bans against cruel or unusual punishment. Officials have scheduled a news conference for later Thursday to discuss the findings.

State prisons director Robert Patton originally said the cause of death was a heart attack, but autopsy results released last week said he died from the execution drugs: midazolam, vercuronium bromide, and potassium chloride.

Lockett, 38, was convicted of shooting Stephanie Nieman, 19, with a sawed-off shotgun and watching as two accomplices buried her alive in 1999.

AFP Photo/Brendan Smialowski

Interested in national news? Sign up for our daily email newsletter!