The Strange Justice Of A Misidentified Suspect And The Media

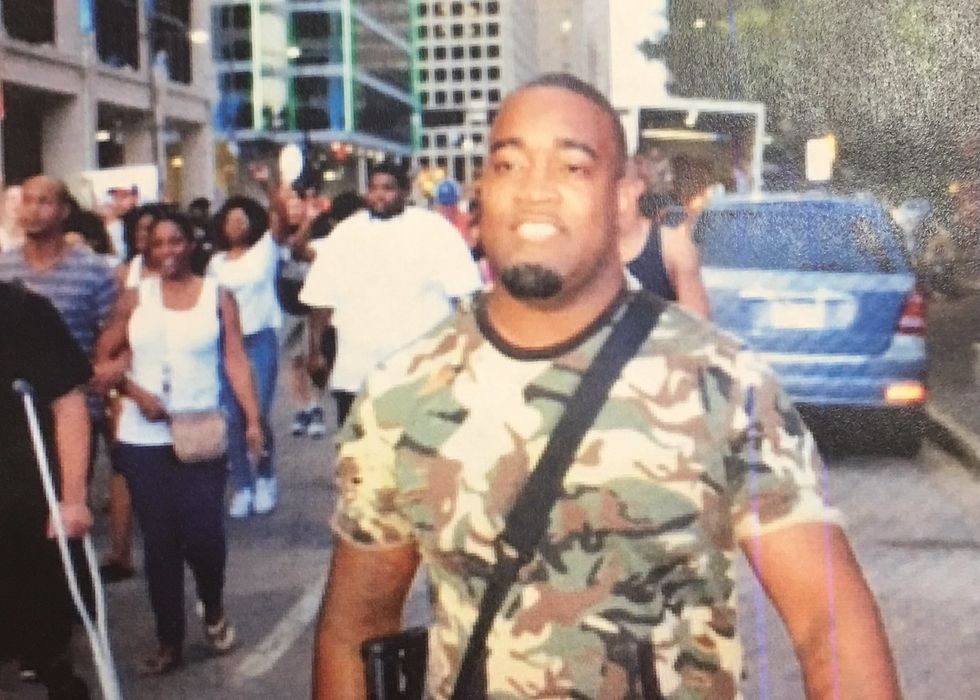

Mark Hughes was innocent. Yet for a while on Thursday night, he became the most notorious criminal in the United States.

Hughes brought along his rifle to a Dallas gathering protesting the police killings of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile. He marched peacefully the entire time, with the legally gun strapped onto his back.

However, once the Dallas Police Department identified Hughes as a suspect in the tragic shooting that occurred later that night, a mass digital witch hunt began.

The DPD posted Hughes’ photo on Twitter, passed out copies to reporters, and described Hughes physically in a press briefing, ordering civilians not to approach him. His face appeared on dozens of national and local television networks. (The photo is still on Twitter as this article goes to press, after over 40,000 retweets.)

https://twitter.com/DallasPD/status/751262719584575488?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw

Justice must be served, and it must be served quickly. But if nothing else, Hughes’ case shows that in hyper-public tragedies like the Dallas shooting, the noble impulse to locate killers in impossibly large public gatherings can shine a spotlight on the wrong people.

It’s a strange kind of justice indeed when seemingly every publication and network accuses an innocent protester of slaughtering five police officers; when the desire to avenge this killing surpasses the need for accuracy.

Of course, a “person of interest” is different than a suspect is different than a criminal. And a man with a gun near a mass shooting is bound to raise questions. But in the age of instant online alerts, an accusation like the one made by Dallas police — and dutifully magnified by a cooperative media — can spread like wildfire. At that point, the court of public opinion rules.

As a handful of publications noted, the false allegations against Hughes bear an eerie parallel to the efforts to identify the Boston marathon bombers.

Reddit and Twitter users speculated in the immediate aftermath of the bombing that its perpetrator was a missing Brown University student, Sunil Tripathi, who was later found dead of unrelated causes. Over a police scanner, someone mentioned the name Mike Mulugeta (who was not a real person). Suddenly, an unclear chain of events and tweets lead journalists from BuzzFeed, Politico, and Newsweek to announce Mulugeta and Tripathi as prime suspects.

The New York Post, meanwhile, published a photo of another two men on its cover, alleging that they were the bombers. How the Post ended up publishing that photo is legally contested, but the paper said in court that Boston police had told them to identify the men.

The Daily Beast also misidentified a suspect at a San Bernardino shooting last December, publishing the photo, employer and property records of the shooter’s brother rather than the shooter himself. A similar circus ensued on social media.

Unlike Hughes, none of these suspects were unequivocally named by police, but, like Hughes, their names and faces soon emerged everywhere. The frantic search for a shooter — any shooter, it seemed — after the attacks began created misinformation on a massive scale.

Hughes turned his gun into police almost immediately, and another suspect was identified. (Perhaps paradoxically, Hughes was helped by another mass media craze: one documenting that he was not, in fact, the shooter.) But did his photo need to be blasted over the airwaves and pasted over Internet to begin with?

Photo from Dallas Police Department Twitter