The Shame Of The 'Where's Nancy?' Republicans -- And How To Stop Them

On Wednesday, President Biden argued that “democracy is on the ballot” this year and he’s right. About 300 heads-we-win-tails-you-lose authoritarian Republican candidates pose, in the words of conservative former Judge J. Michael Luttig, “a clear and present danger” to the republic.

Take the Republican candidate for governor of Wisconsin, Tim Michels:

\u201cTim Michels: "Republicans will never lose another election in Wisconsin after I'm elected governor."\n\nHe\u2019s saying the quiet part out loud.\u201d— The Republican Accountability Project (@The Republican Accountability Project) 1667331470

That’s scary enough. What’s less understood is that decency is on the ballot, too, and speaking out against cruel candidates could be a good closing argument for Democrats trying to motivate decent people — many of them independents — who make up their minds about whether to vote at the last minute.

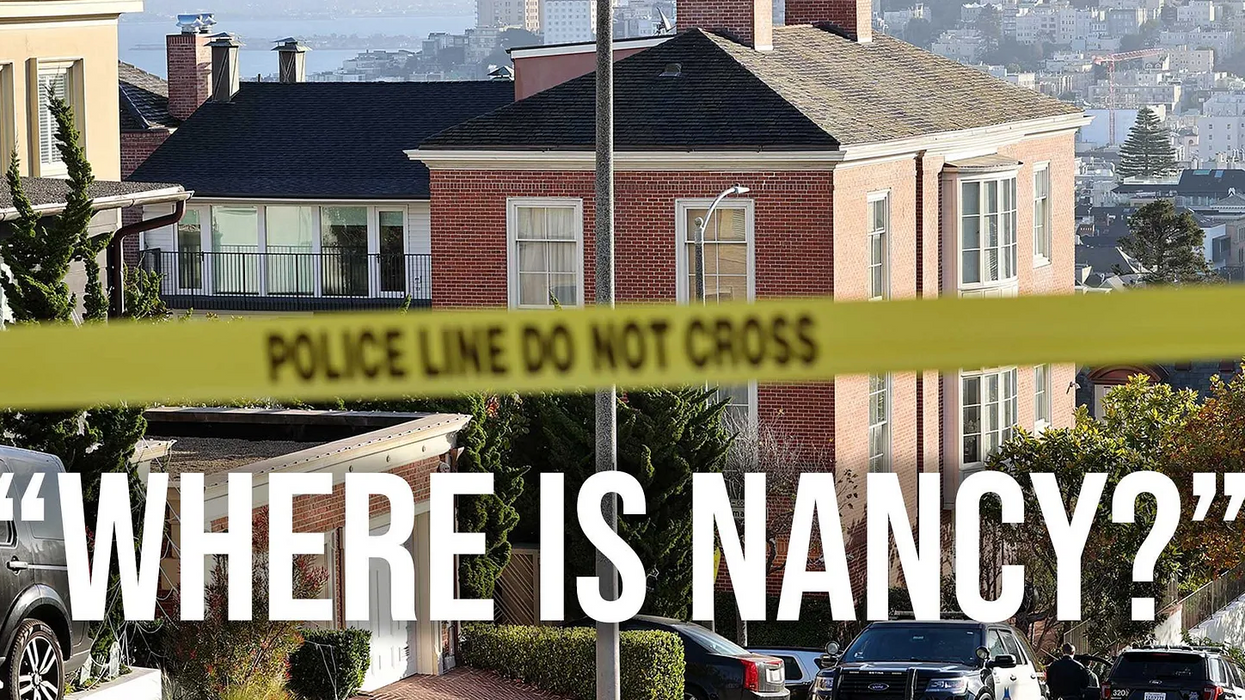

Yes, voters care a lot more about inflation than the way politicians treat each other. And Democratic operatives are concerned that Biden’s speech reinforces the idea that the midterms are a referendum on him, which they don’t want it to be. But the Pelosi story brings Trump’s depravity — a huge motivator in the last two elections — back into the conversation at the right time for Democrats and it helps motivate the hundreds of thousands of volunteers they need for their get-out-the-vote operations by directly connecting January 6 to November 8. As Biden noted, the man who attacked Paul Pelosi used the same words as the insurrectionists: “Where is Nancy?”

But it wasn’t the attack of the nut job that so shook Biden and, arguably, American democracy. It was the reaction to it inside the GOP — the appalling fact that instead of coming together behind common decency, as every Democrat did after the 2018 shooting of GOP Rep. Steve Scalise by a leftwinger at a congressional baseball game, so many Republicans turned the whole thing into a cruel joke. Most important, these “‘Where’s Nancy?’ Republicans” refused to condemn political violence. For them, it’s almost as if they want the whiff of it to be part of their political identity — like support for tax cuts or opposition to mail-in ballots.

The problem is that violence is not just another position or tactic. It’s the gateway to true fascism, which has always had physical menace at its core. When you read accounts of Mussolini’s Black Shirts or Hitler’s Brown Shirts before the dictators took power, the thugs aren’t always beating people up on direct orders. They’re often doing so in the shadows, inspired by propaganda and covered by lies.

Trump peddled a ludicrous lie about the Pelosi attack. Per The New York Times:

“Weird things going on in that household in the last couple of weeks,” Mr. Trump said on the Chris Stigall show, winking at a lie that has flourished in right-wing media and is increasingly being given credence by Republicans. “The glass, it seems, was broken from the inside to the out — so it wasn’t a break-in, it was a break out.

This appeared as a “Political Memo” sidebar on page A14 in the print edition of the Times. In other words, it’s being played as just another “shocked but not surprised” story about Trump and the GOP.

I’ve used the “shocked but not surprised” formulation myself in the past but I now view it as a dangerous evasion of moral responsibility — the equivalent of offering “thoughts and prayers” after a school shooting. Think about all the sins it covers.

Trump, who is heavily favored to be the 2024 Republican nominee for president, is an Orange Alex Jones who peddles sick lies about an 82-year-old man in the ICU and our reaction is: “shocked but not surprised.”

I think we need to redefine major news so that it’s not only what’s new and surprising but also what’s shocking and dangerous to democracy, even if perfectly predictable.

So beyond voting next week, what do we do? Just as America is built on a set of ideas — the rule of law, fair play, the peaceful transfer of power — the road back to decency and democracy begins with ideas that eventually work their way into our thinking. Here’s one to consider, from a formidable public intellectual I always enjoyed interviewing.

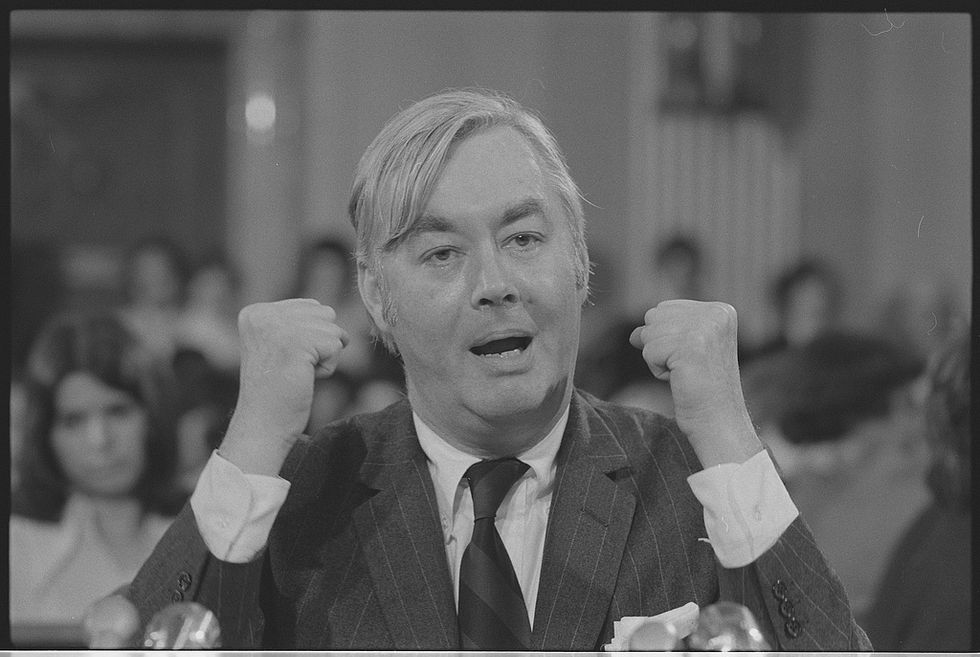

Daniel Patrick Moynihan, who died in 2003, will soon be best-known as a train station — well, actually, as Moynihan Train Hall, the spectacular new $1.6 billion dollar transit hub and concourse that he envisioned and that finally opened in the 100 year-old Farley Post Office Building across Eighth Avenue from Pennsylvania Station in Manhattan.

In the 20th century, Moynihan was famous as a four-term senator from New York and a combative UN ambassador, but he was also a sociologist who wrote 15 books. In a landmark 1993 article in The American Scholar, titledDefining Deviancy Down, Moynihan built on the work of sociologists Emil Durkheim and Kai T. Erikson in explaining that when a society faces rising crime, it responds by “redefining deviancy so as to exempt much conduct previously stigmatized.”

Moynihan wrote just after murders in New York City had peaked in 1990 at 2,245 — an average of more than seven a day. Last year brought 485 murders — between one and two a day — and that’s up 25 percent from a few years ago. What changed, in New York City and across the country? Possible explanations include more cops, new strategies for community policing, rigidly enforced gun control, and declining birth rates (partly attributable to increased abortions), among others. The larger idea that unifies them is that society should stop being numb to the problem — stop defining it down. Crime was still sky-high in 1993, but Moynihan saw reasons for hope:

I was hugely encouraged by an address which [New York City] Police Commissioner Raymond Kelly gave to the FBI's Second Symposium on Addressing Violent Crime Through Community Involvement. His address was entitled "Toward a New Intolerance" In it, he called for an intolerance of violence, an end to what Judge Edwin Torres describes as our "narcoleptic state" of acceptance….

… If our analysis wins general acceptance, if, for example, more of us came to share Judge Torres's genuine alarm at "the trivialization of the lunatic crime rate" in his city (and mine), we might surprise ourselves how well we respond to the manifest decline of the American civic order. Might.

Moynihan’s analysis did win “general acceptance” and — through the efforts of thousands of people in hundreds of cities — crime rates plummeted and stayed low for years.

Now, with crime ticking up, Republicans have found an issue that works for them politically. But their hypocrisy knows no bounds. After January 6, their position on the Capitol Police was: Back the blue— unless it’s a coup. After the attack on Paul Pelosi, their take is: the police are lying about what happened. The intruder was actually a gay hippie prostitute.

The lying, hypocrisy, and rampant election denying add up to a different kind of “decline of the American civic order.” The broad answer to the present crisis is to stop defining political deviancy down — and work like hell to save decency and democracy. We might surprise ourselves how well we respond. Might.

Jonathan Alter is a bestselling author, Emmy-winning documentary filmmaker, and a contributing correspondent and political analyst for NBC News and MSNBC. His Substack newsletter is OLD GOATS: Ruminating with Friends.

Reprinted with permission from OLD GOATS