California’s Darrell Issa Loses Power With House Oversight Committee Post

By Noah Bierman, Tribune Washington Bureau (TNS)

WASHINGTON — For four years, Rep. Darrell Issa presided over one of the highest-profile oversight committees in Congress, becoming a fixture in the national news as he took the Obama administration to task for everything from bank bailouts to corruption in Afghanistan.

Only three months ago, the California congressman unveiled a portrait of himself to hang proudly in the committee hearing room.

“Click LIKE to thank Chairman Issa for his tireless commitment to transparency and for his dedicated service to the American people,” the oversight committee Facebook page suggested as the portrait was hung.

Just days after his successor took over at the helm in January, though, the new painting vanished from the hearing room. It now hangs in a private committee anteroom, beside a coat rack and a television screen.

Its journey echoes the waning influence of the California Republican, whose confrontational style managed to wear not only on Democrats, but on members of his own party.

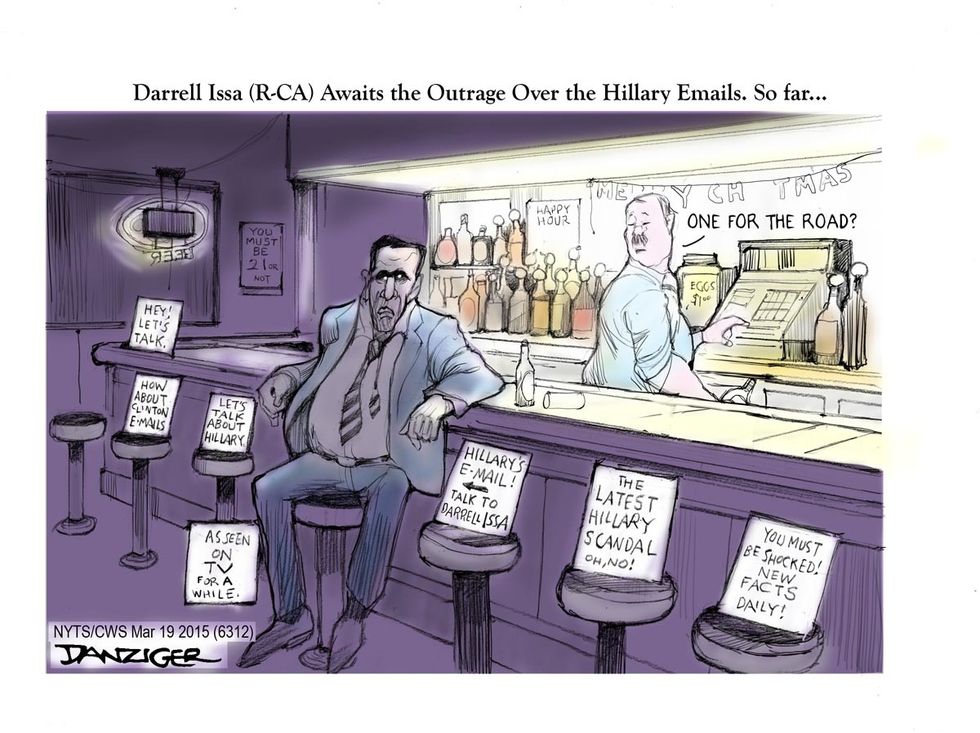

Issa used his position atop the House Oversight and Government Reform Committee to relentlessly poke at President Barack Obama over Benghazi, the Internal Revenue Service, the “Fast and Furious” failed gun sting, and any number of topics that made for high theater and cable cameos. But Issa’s investigations often failed to show direct culpability on the part of the White House or Obama, whom he once called “one of the most corrupt presidents in modern times.”

Issa’s influence began to wane last year, when party leaders diverted attention from his high-drama investigation of the deadly 2012 attack against U.S. personnel in Benghazi, Libya, by establishing a new committee to focus on the incident.

Then they thwarted his attempt to secure a rare exception to the limit on how long he could lead the oversight committee. (He served one term as the committee’s top Republican, when Democrats held the majority, and then a pair of two-year terms as its chairman.)

His successor, fellow Republican Rep. Jason Chaffetz of Utah, campaigned to succeed Issa on a promise to run the committee differently. When he took over in January, Chaffetz replaced many of Issa’s staff members and engineered the move of portraits of Issa and other former chairmen.

“Darrell Issa didn’t do many reports,” Chaffetz told reporters in December, after Republican leaders tapped him, according to Roll Call. “(He) did big press releases.”

“It’s not the ‘Jason Chaffetz Show,'” he said at another point.

Issa, now beginning his eighth term in Congress, finds himself at a crossroads.

Despite a personal fortune that gives him a huge advantage in elections, there was little clamoring among California Republicans for him to reprise a run for the Senate seat that Democrat Barbara Boxer will relinquish after the 2016 election. Issa spent $10 million trying to unseat her in 1998 but failed to win the Republican nomination.

He appears unlikely to follow the path of one of his predecessors in the post, former Rep. Henry A. Waxman of Beverly Hills, a Democrat who left Congress this year after four decades with a legacy as a legislative titan. Two factors get in Issa’s way: The Republican Party imposes term limits on its chairmen, and many members of the party philosophically oppose the type of sweeping legislation championed by Waxman and other liberals.

Issa’s allies say he retains leverage; he is a key ally to Silicon Valley, leading a subcommittee that oversees patents. And Issa has succeeded before in surprising ways, even as he took on a highly partisan role: He worked with Democrats to oppose anti-piracy measures that opponents said would undermine free speech on the Internet.

His new committee assignments — he was also named to the House Foreign Affairs Committee in December — will put him in the middle of compelling issues.

“He’s very much going to be active and robust in policy and intellectual property issues, which is really in his wheelhouse,” said Kurt Bardella, a former aide to Issa who is now a private media consultant. Issa, who made his fortune manufacturing anti-theft devices for cars, has held 37 patents, according to his office.

Issa declined a request to discuss his plans or past performance. When a reporter approached him in a House hallway to request an interview, he refused and said that the result would be a “hit piece.”

Just a few minutes later, the committee Issa used to lead met for the first time since he handed over the gavel to Chaffetz. The top Democrat on the committee, Maryland Rep. Elijah E. Cummings, opened his remarks with a call for a “new beginning.”

“The last four years were filled with acrimony, partisanship and sometimes vulgar displays,” Cummings said. “They were a stain on this committee’s integrity and an embarrassment to the House of Representatives.”

Cummings was a principal figure in one of Issa’s most controversial moves, which occurred during a hearing last year that was devoted to IRS scrutiny given to some conservative groups’ tax-exempt status.

Issa, angry after former IRS Director Lois Lerner pleaded the Fifth Amendment to avoid answering questions, called the meeting adjourned even as Cummings tried to speak. Cummings protested that it was a “one-sided investigation” as Issa shut down the Democrat’s microphone and began to leave.

“I am a member of the Congress of the United States of America. I am tired of this,” Cummings said, his arm shaking and his words echoing through the large chamber even without amplification. The dispute, caught on video, spread widely over social media.

For many, the incident illustrated how decorum had fallen in Congress, as genteel formalities have given way to unvarnished contempt among partisans. But it specifically tarnished Issa and contributed to Republicans’ distancing themselves from him.

In a 348-page report, Issa cited a number of accomplishments from his four years at the helm of the oversight committee. They include 23 laws passed, including the Digital Accountability and Transparency Act, which required federal agencies to put more detailed budget information online for public scrutiny. Issa also pointed to more than 100 subpoenas he issued — a tactic that critics have assailed as excessive — and to nearly 60 reports released.

But some of the highest-profile investigations have failed to live up to the initial hype. For example, his final investigation on the IRS targeting conservative groups failed to show evidence of White House involvement, despite Issa’s statement in 2013 that “this was a targeting of the president’s political enemies” that was discovered only after Obama’s re-election. His statement last year that he suspected former Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton had told former Defense Secretary Leon E. Panetta to “stand down” during the attack on Americans in Benghazi was not substantiated by two separate congressional reports.

Yet even some Democrats say that Issa helped Republicans make significant gains in the November election.

“There’s no question he accomplished part of his mission, which was to do damage to the president,” said Rep. Gerald E. Connolly, a Virginia Democrat who serves on the oversight committee. “The relentless headline-grabbing, breathless subpoenas and hearings, and charges certainly served a purpose, even though there was very little there, it turns out.”

(c)2015 Tribune Co., Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC

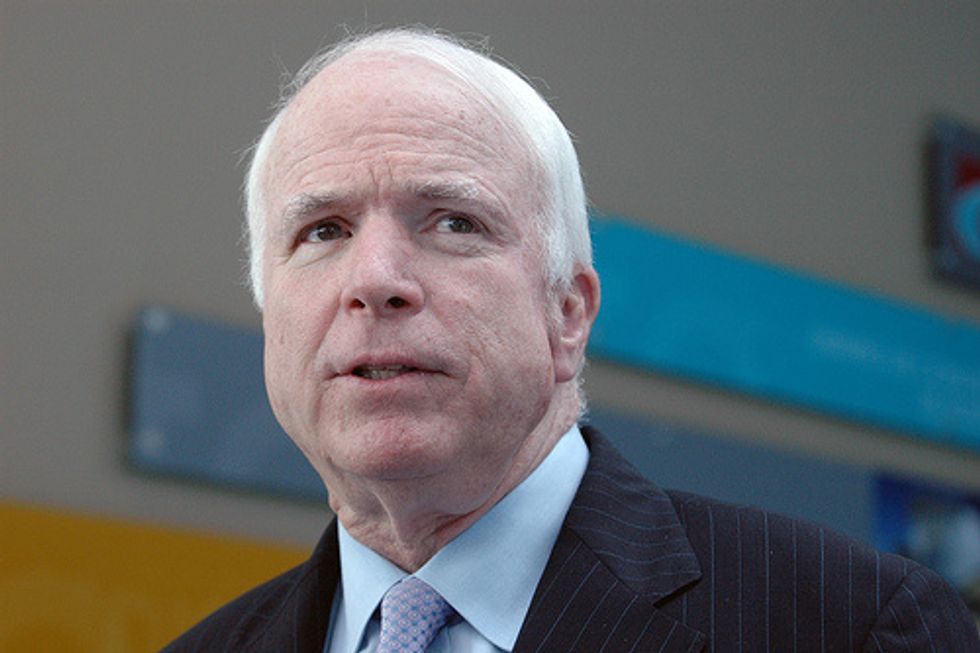

Photo: Stanford Center for Internet and Society via Flickr