By Steven Rea, The Philadelphia Inquirer (TNS)

The protagonists of “Woman in Gold,” starring Helen Mirren, and “Seymour: An Introduction,” a documentary by Ethan Hawke, are both in their 80s, resilient individuals whose strength of spirit works like a lighthouse beam showing the way. In each of those new films, the light shines on a younger protege. In “Woman in Gold,” based on a true story, it’s a hapless lawyer played by Ryan Reynolds. In “Seymour: An Introduction,” it’s the filmmaker — and actor — Hawke, half the age of his subject, composer and teacher Seymour Bernstein.

Here, Mirren and Hawke illuminate:

“Imagine that you are home, with all of your family, all of your things, everything you’ve bought and the things that were passed on to you from your parents and your grandparents,” Helen Mirren says. “And then in walk these people who, first of all, say, ‘We’re having that, we’re taking this, and by the way, you don’t live here anymore.’

“And then they kill your whole family.”

That’s pretty much the scenario that Maria Altmann, daughter of wealthy Viennese Jews, witnessed in 1938, when Nazi Germany annexed Austria. Troops of the Third Reich rolled in, seizing property and businesses from the long-established Jewish community.

In “Woman in Gold,” the Oscar-winning actress of “The Queen” brings the intrepid Altmann back to life. Escaping Austria with her new husband, and settling in the United States, after two years in England, Altmann “had to start absolutely from zero,” Mirren says. “But she was young. She was in her early 20s, so she was active and up for an adventure.”

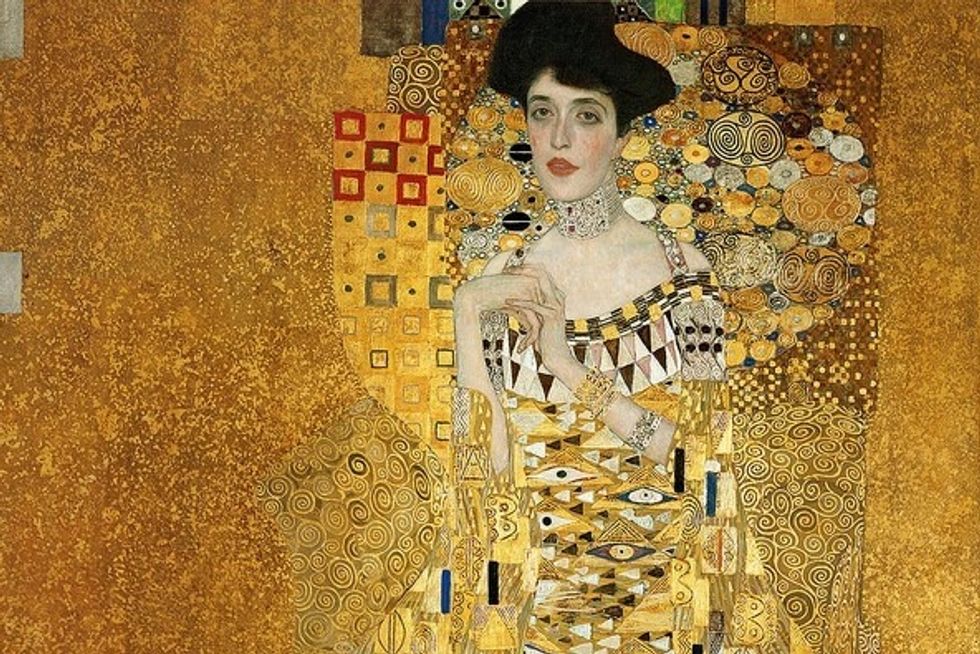

Perhaps her greatest adventure — a historic one — was the five-year-plus legal battle to reclaim a group of paintings by Austrian artist Gustav Klimt that hung in her family’s apartment. The most notable piece was a portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer, Altmann’s aunt — a serene and seductive woman draped in gold, and painted in gold leaf. Seized by the Nazis, the Klimts ended up after World War II in Vienna’s Belvedere Palace museums, owned by the Austrian government.

“Woman in Gold, directed by Simon Curtis, chronicles Altmann’s daunting fight for restitution. Ryan Reynolds, bumbling and bespectacled, stars as E. Randol Schoenberg, an inexperienced Los Angeles lawyer and family friend who, at first reluctantly, took on Altmann’s case — and ended up arguing it before the Supreme Court.

Along the way, the mismatched duo — she, in her 80s, headstrong and heartsick over what her homeland had done, and he in his 40s, the grandson of expatriate Austrian composer Arnold Schoenberg — forged a lasting bond. Altmann died at age 94 in 2011. She won her battle to reclaim the Klimt in 2006. The portrait of her aunt now hangs in the Neue Galerie in New York.

“Woman in Gold” was shot in Vienna, London, and Los Angeles. Mirren says that even though the case of “Republic of Austria v. Altmann is only a decade gone, the institutional,and cultural hostility depicted in the film — with government officials and museum directors doing everything they could to keep the Klimts — has been vanquished.” When she, Reynolds, and Daniel Bruhl, playing an investigative journalist allied with Altmann, were in Vienna, they were greeted warmly.

“The Viennese were incredibly welcoming, I have to say,” Mirren recalls. “You know, they are the villains of the piece, because they were the villains of the piece. But time has moved on.

“I personally was invited to the Town Hall by the mayor and presented with the keys of the city. He said, ‘Maria Altmann was a very important person in our history…she made us understand what actually occurred when the Nazis invaded, and how Viennese citizens contributed to what had happened,’ and then how they went into denial as soon as the war was over….

“I would say that they have really turned around,” Mirren ventures. “You know, history gets rewritten very quickly, and suddenly it’s ‘Oh no, we didn’t know, we had no idea.'”

“Woman in Gold,” then, serves as a reminder.

“We certainly do need reminding,” Mirren says. “I love the line in the film, when Maria says, ‘Because people forget, you see. Especially the young.'”

___

Ethan Hawke found himself at a dinner party a few years ago, seated next to a man more than twice his age, a pianist, composer, and teacher named Seymour Bernstein. By evening’s end, Hawke was so taken with his fellow New Yorker that he felt the need to meet again, to continue the discussion about art, music, acting, and life. Then the “Boyhood” and “Training Day” star started thinking that what he really needed to do was make a film about the man.

“Seymour: An Introduction” is that film.

“I was turning 40,” says Hawke, recalling that dinner and how he started spilling his guts to the stranger by his side about career anxieties. “I’d always been the youngest in the room, and all of a sudden I really wasn’t anymore, and I was being expected to deliver and be a professional….I just felt a certain pressure to take off the student cap — and I really didn’t want to.

“And Seymour has an incredible ability to listen and key in on what somebody’s trying to say….But I realized, talking to him, how any issues of anxiety or pressure in acting are really a fraction of what a concert pianist experiences. The pressure and intensity of one performance, one memory slip, one physical misstep, and your performance at Carnegie Hall is forever ruined….

“So he knows that feeling. And when I left, I felt really privileged. That was the feeling that ultimately led to making me want to do this. I felt an obligation that more people should get a chance to meet him.”

Bernstein, now 87, is indeed worth meeting. The conversations Hawke has with the octogenarian musician are illuminating. So are the moments when Bernstein is filmed teaching his students, or being interviewed by Michael Kimmelman, the New York Times critic who was all of five years old when he started taking lessons from Bernstein.

It’s easy to see why Hawke — and the others — are inspired.

“Seymour is not self-serious, he’s not pretentious,” the actor says. “He’s full of a tremendous amount of love and wit….And yet a lot of people who spend their life in the arts, they sometimes can be defeated by failure or defeated by success. It almost leaves you no recipe for happiness.”

Bernstein has found that recipe, and Hawke is eager to share it.

Photo: freeparking :-l via Flickr