Republican ‘Takers’ Take Down the Establishment

Just as Donald Trump did a Super Tuesday stomp on the Republican establishment, the establishment showed why it deserved the rough treatment. The Republican Senate leadership yet again announced its refusal to consider anyone President Obama nominates for the Supreme Court until after the presidential election.

It is the job of the U.S. Senate to hold hearings on, and then accept or reject, the president’s choice. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell and Judiciary Committee Chairman Chuck Grassley said they will not take on the work — while showing no inclination to forgo their paychecks.

Talk about “takers.”

Yes, talk about “takers.” That’s how Mitt Romney described Americans benefiting from Medicare, Social Security, Obamacare and other government social programs during his failed 2012 run for president. Never mind that most of the “takers” have also paid for some of what they have received.

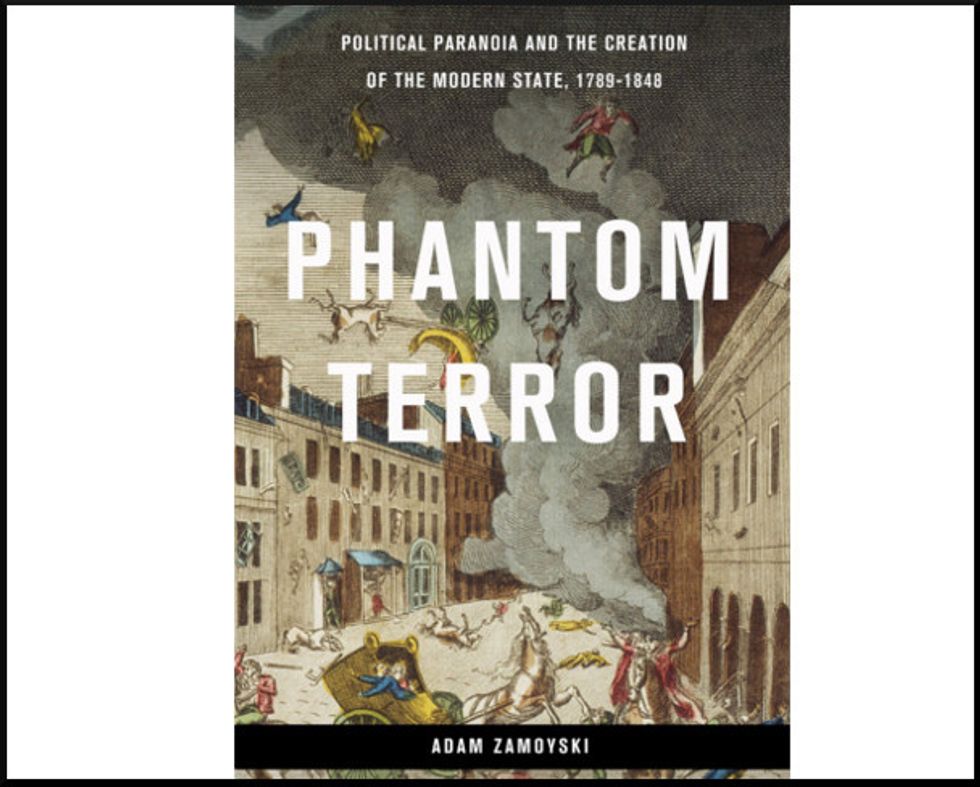

Working-class Republicans have finally rebelled against the notion that everything they get is beneficence from the superrich — and that making the superrich super-duper-rich would drop some tinsel on their grateful heads. They were done with quiet protest and ready to take down the Republican bastille, stone by stone. And the angrier Trump made the establishment the happier they were.

The Bastille was the symbol of France’s Old Regime. The storming of the prison in 1789 kicked off the French Revolution.

Republican disrupters from Newt Gingrich on down liked to talk about a conservative revolution. They didn’t know the first thing about revolutions. This is a revolution.

Back at the chateau, Republican luminaries were calmly planning favors for their financiers. They assumed their party’s working folk would fall in line — out of both hostility to Democrats and through hypnosis.

So you had Jeb Bush amassing an armory of campaign cash over bubbly and hors d’oeuvres at the family estate in Maine. You had Marco Rubio devising a plan to do away with all capital gains taxes — the source of half the earnings for people making $10 million or more. You had Ted Cruz concocting a plan to abolish the IRS. (Without the IRS, only the working stiffs would be paying taxes, the money automatically deducted from their paychecks.)

Not much here for the alleged takers, who actually see themselves as “taken from.” Unlike the others, Trump wasn’t going after their benefits. He even praised Planned Parenthood, noting it provides a variety of health services to ordinary women.

Trump would be a disastrous president, of course. But he knows how to inspire the “enraged ones.” In the French Revolution, the enraged ones were extremists who sent many of the moderate revolutionaries to the guillotine. (The enraged ones also ended badly.)

As the embers of Super Tuesday still glowed, The Wall Street Journal published the following commentary by one of its Old Regime’s scribes:

“To be honest and impolitic, the Trump voter smacks of a child who unleashes recriminations against mommy and daddy because the world is imperfect,” Holman Jenkins wrote. Take that.

No responsible American — not the other Republicans and certainly not Democrats expecting strong Latino support — would endorse Trump’s nasty attacks on our hardworking immigrants. But large-scale immigration of unskilled labor has, to some extent, hurt America’s blue-collar workers, and not just white ones.

Democrats need to continue pressing reform that is humane both to immigrants already rooted in the society and to the country’s low-skilled workforce. Do that and the air comes whooshing out of Trump’s balloon.

Back in Washington, the Republican leaders will probably continue to avoid work on this issue or a Supreme Court nominee or anything else Obama wants. They should enjoy their leisure. After Election Day, many may have to look for real jobs.

Follow Froma Harrop on Twitter @FromaHarrop. She can be reached at fharrop@gmail.com. To find out more about Froma Harrop and read features by other Creators writers and cartoonists, visit the Creators Web page at www.creators.com.

COPYRIGHT 2016 CREATORS.COM

Photo: Donald Trump points at a supporter at a polling place for the presidential primary in Manchester, New Hampshire February 9, 2016. REUTERS/Rick Wilking