A Top Fundraiser For Obama Turns From Wall Street To Drones

By Max Abelson, Bloomberg News (TNS)

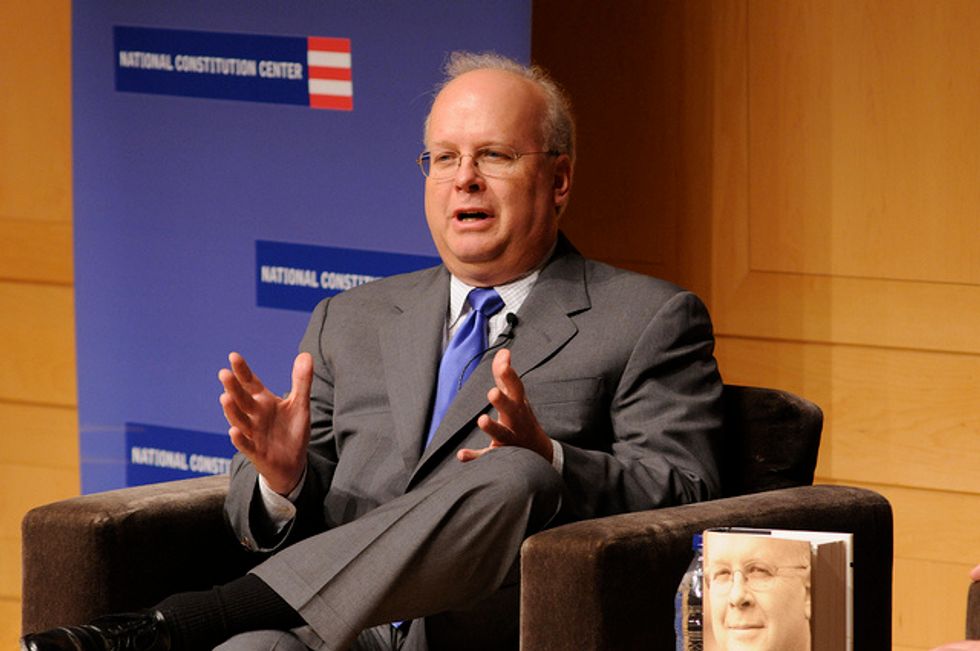

WASHINGTON — Wearing cuff links with the U.S. presidential seal, Robert Wolf was explaining why he loves drones and wants to help big companies fly them.

His new Times Square office features a Barack Obama mouse pad, campaign mug, and cue ball, plus photos of the two men playing golf and basketball together in shorts, having a chat and smiling with family. The only thing that interrupted Wolf’s praise last month for Measure, the drones arm of his advisory company, was some White House news flashing across his TV screen.

A former head of UBS Group AG’s Americas unit and one of Obama’s most visible Wall Street friends, Wolf murmured the headline to himself. When he saw it was minor, he returned to explaining how corporations could use unmanned aircraft to spray pesticides, or inspect pipelines — and let Measure handle everything from getting government permission to arranging flights and analyzing data.

“I’ve been in business for 30 years — this is the most exciting thing I’ve ever done,” said Wolf, who left UBS during Obama’s 2012 re-election campaign to start 32 Advisors, which also offers economic advice, brokers infrastructure deals, and helps foreign governments get investments. “Just to be clear, this is going to change the landscape.”

Change won’t be easy. With Measure approaching its first anniversary next month, interviews with its executives and partners show how hard it is to build a business in a new field, even with connections to presidents. These are still early days for an industry that’s gotten less traction than the toys that hobbyists can buy for $100 or the weapons used by the Central Intelligence Agency to hunt terrorists.

Commercial drone flights in the U.S. are mostly banned. Few companies have won permission from the Federal Aviation Administration for takeoff, despite Amazon.com Inc.’s research into unmanned deliveries and stunts by pizzerias. Bad news hasn’t helped. This year a drone crashed onto the White House grounds, one was discovered carrying about seven pounds of crystal methamphetamine in Tijuana, Mexico, and another, possibly radioactive, was found on the roof of Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s Tokyo office.

Wolf has never seen a commercial drone fly and wouldn’t name any paying U.S. clients. Still, the 53-year-old chairman of Measure envisions a future stretching from Gabon to Australia.

Instead of building or owning drones, Measure wants to advise clients and be the middleman arranging flights. The plan is to pick the best one for the job, maybe a three-pound kit that can respond to weather conditions or a ten-foot-wide craft that can stay aloft for 24 hours.

Wolf, who has golfed at least five times with Obama on Martha’s Vineyard, bundled more than one million dollars for his campaigns and was named to White House advisory groups on jobs and economic recovery, isn’t the only one with Washington ties. Measure Chief Executive Officer Brandon Torres Declet was a congressional counsel and lobbyist. President Justin Oberman helped establish the Transportation Security Administration. Senior adviser Jane Holl Lute was the Department of Homeland Security’s deputy secretary until 2013. Former Obama Cabinet member Austan Goolsbee heads 32 Advisors’ economic team.

“Connections open up possibilities and opportunities, except when they don’t,” Lute said. “And they don’t when they don’t fit. And sometimes you have to try a lot of connections before you get a good fit.”

Wolf said he doesn’t email world leaders he knows to ask for help because it wouldn’t show respect. One reaches out instead, he explained, to chiefs of staff and ministers.

Chatting with Obama about the business could be awkward. Weaponized drones have killed civilians including an American and an Italian held hostage by al-Qaida in Pakistan this year, and the mines and pipelines Measure wants to work with can be politically touchy.

Declet, a former counsel to Senator Dianne Feinstein (D-CA), said he won’t let politics get in the way.

“I disassociate being a Democrat from actually being a businessperson,” Declet said. “Being an entrepreneur is about breaking barriers and making money.”

Drones need all the regulatory help they can get. The FAA has granted 244 exemptions, most of them this month, including to Dow Chemical Co. for plant inspection and Union Pacific Corp. for assessing damage after train accidents.

In February, the FAA proposed rules that would keep flights from going too high, long, or fast, over crowds, or out of the sight of operators. A letter from Measure this month asked the FAA to soften the visibility rule.

Government ties are especially valuable to businesses that need exemptions from regulators, according to David Leblang, chairman of the University of Virginia’s politics department.

“Is it fair?” he said. “No. That’s the simple answer.”

A project in Africa shows how far Wolf’s network stretches. He went to a conference last May in Gabon, where he knows President Ali Bongo Ondimba, and met Devry Ross, a former Morgan Stanley vice president. Ross, who knows the head of utility Societe d’Energie et d’Eau du Gabon, became Measure’s senior adviser for Africa. The company, controlled by Veolia Environnement SA, became a client.

“It was pure luck,” said Declet. “Here we had Robert and Devry in the same place at the same time.”

Declet met her in Gabon in February to do an analysis that he said cost the client about $50,000.

According to Measure’s report, muddy roads and rough terrain have impeded power-line inspection. It recommends twice-a-year drone flights with video, explaining that Measure can meet with officials including Bongo’s chief of staff to seek permission. Jean-Paul Camus, head of the utility, didn’t respond to messages.

Gabon’s president was voted into office in 2009 after his late father’s four-decade rule. The U.S. State Department has urged the government to end corruption while saying ties between the countries are strong.

“I’m comfortable with President Bongo, I’ve met him multiple times,” Wolf said. “You cannot be completely idealistic when you’re dealing with these countries. Because I think that part of these countries getting to where you want them to be is making sure they have the right infrastructure.”

Wolf spent 18 years at UBS, becoming president of its investment bank. His former colleague Phil Gramm, the Texas Republican who joined the Swiss bank after leading the Senate Banking Committee, doesn’t see anything wrong with a client wanting to work with Wolf because of his connections.

“If I’ve got to deal with government and I need to get a license like anybody else, what would be wrong with me finding someone like Robert Wolf to help me make the strongest case I can?” said Gramm, a vice chairman of UBS’s investment bank until 2012. “If I want to fly a drone and I’m looking at people that can help me make my case for a license, who am I going to pick, somebody who came in off a turnip truck?”

Measure is interested in working with companies that mine bauxite in Guinea, copper in Zambia and gold in Tanzania, according to Ross and Declet. Mark Stevens, who heads the company’s Australian wing, said that while six clients there had signed up for advice, dipping commodity prices have slowed plans to work with mines.

There are prospects at home, too. Measure is leading a study with the American Farm Bureau Federation to see how drones can boost crop yields and cut costs. It has discussed them with PepsiCo Inc., the world’s largest snack-food producer.

“At the end of the day he wants to make money,” Pepsi CEO Indra Nooyi, who has known Wolf since his UBS days, said this month. “But there’s an incredible way he deals with that.”

Last week, Measure published a study on disaster response for the American Red Cross whose sponsors included drone-makers Boeing Co. and Lockheed Martin Corp. The 52-page report explains how drones can fight fires, assist in search and rescue and deliver food.

“I don’t think we’re ready to do that,” Richard Reed, who develops disaster programs for the nonprofit, said in Washington after the report was made public, referring to regulation.

There are other obstacles.

“Drones crash,” said Greg McNeal, who advises Measure and studies technology at the Pepperdine University School of Law. “Drones malfunction. Camera equipment crashes. People just make errors. They drop things on landing or takeoff. They hit unexpected obstacles in the air.”

In December, two months after an Air Force report blamed a drone crash in Nevada on wind and pilot error, that state’s governor joined a senator and congressman to watch a test flight. The drone flew a few feet and crashed.

“People will just say, ‘It’s too early! It’s too early!'” said Oberman, Measure’s president. “We don’t accept that.”

He and Declet were looking to raise money for a drone startup last year when a friend of Declet’s helped introduce them to Wolf, whose advisory business has done work for private-equity company Fortress Investment Group LLC and hedge fund York Capital Management.

“About 20 minutes into the meeting he said, ‘You guys should join 32 Advisors,'” Oberman said.

Wolf, whose University of Pennsylvania football jersey number inspired the company’s name, also told them he didn’t like their proposal to own drones and lease them out. He sent them into a conference room to come up with a different plan.

“I’m incredibly transparent,” said Wolf, who speaks with the stretchy vowels of his Massachusetts hometown outside Boston and keeps a photo of Red Sox hitter David Ortiz in his office. “Most people say Robert Wolf would be a fastball pitcher if he were in the major leagues. He has no curve in his game.”

Despite outbursts that he and his colleagues call “minute madness,” Wolf can put even the most powerful people at ease. “He’s so warm, and he’s so approachable,” said Commerce Secretary Penny Pritzker, who knows Wolf from Obama campaigns. When she met Wolf and some clients and colleagues in New York this year, she said, it was helpful for everyone.

“I want to speak with business leaders across all spectrums of our economy,” she said. “And he was delivering the secretary of commerce.”

Photo: 32Advisors via Twtitter