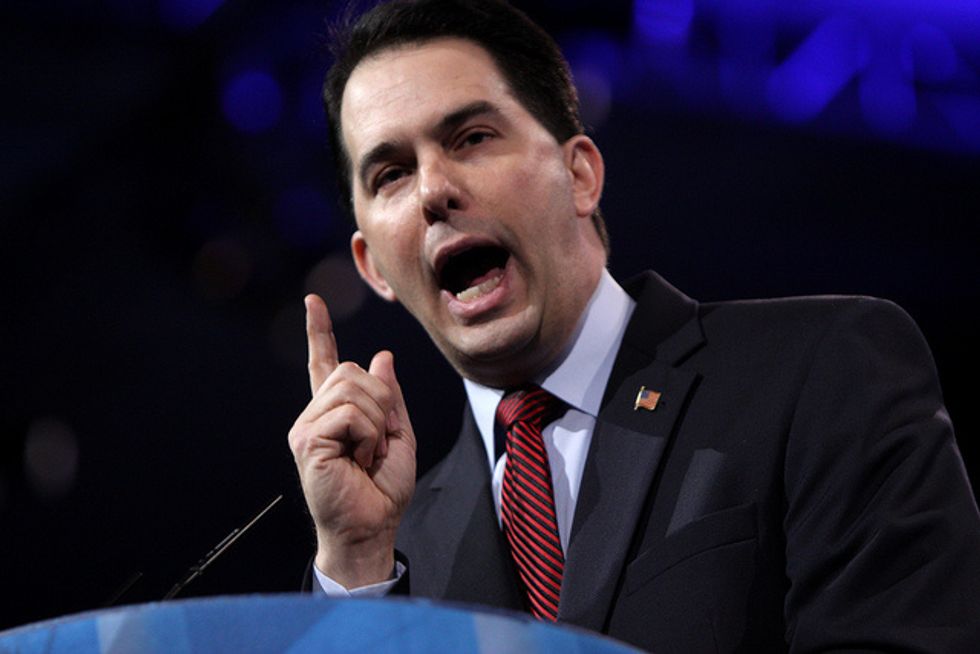

Scott Walker Faces Higher Hurdles Than Polls

By Jonathan Bernstein, Bloomberg News (TNS)

How can we tell if Scott Walker’s polling surge means anything?

Walker has been doing well for three weeks now — including in a new Iowa survey putting him firmly in the lead (albeit with only 25 percent of the vote) and a national poll on Tuesday showing him just ahead of the rest of the pack.

Here’s the thing: Anyone can get a bubble like this. It happened to Michele Bachmann and Herman Cain (among others) in 2012. Before the current cycle is through, even the most unlikely presidential contender — George Pataki or Carly Fiorina or, for that matter, Joe the Plumber — could surge after rave reviews from a speech or a successful debate.

I wouldn’t spend a lot of time studying the polls to find out how real Walker’s numbers are. We already know that most voters had barely heard of the Wisconsin governor a month or so ago, and that he’s attracted excellent coverage, especially in Republican-aligned media, over the last several weeks.

The first thing to watch for real is whether he receives a flood of endorsements from politicians, interest-group leaders, campaign and governing professionals, and other important party actors.

And a second indication that Walker is gaining ground would be if some possible rivals drop out. In particular, watch four other Republican governors who have started out slowly or appear to be struggling: Chris Christie, Bobby Jindal, John Kasich and Mike Pence. If one or more drop out in the next few weeks, it may be because uncommitted resources are drying up and because the people they are reaching out to are telling them 2016 isn’t going to be their year.

The lack of such signs was key when Mitt Romney made a big splash about running. Even though he was polling well, he quickly gave up. Nor did the party immediately rally around Jeb Bush after he first expressed interest — in contrast to the early acclamation his brother received in the 2000 cycle. Jeb has chosen to fight it out.

Every politician has a personal calculation of what he or she is willing to risk on any particular campaign. Overall, however, if people are still jumping in, it means the race is wide open. If candidates are leaving, this probably indicates that most party factions have committed somewhere, even if they haven’t said so publicly.

Walker appeared to be a formidable contender even before his surge, and he’s in better shape now than he was a month ago. But until the party sends clear signs it is beginning to decide on its nominee, I’m leaving him where I’ve had him for a while: in a top tier with Bush and Florida Senator Marco Rubio. Nothing more.

Add Bernie Sanders, Jim Webb and Martin O’Malley to that list: A polling surge by one of the also-ran Democrats would capture the attention of the press, which would love to have a competitive Democratic nomination fight.

Jonathan Bernstein is a columnist at Bloomberg View. He can be reached by email at jbernstein62@bloomberg.net.

Photo: Gage Skidmore via Flickr