Stress Reaction May Be In Your Dad’s DNA, Study Finds

By Geoffrey Mohan, Los Angeles Times (TNS)

Stress in this generation could mean resilience in the next, a new study suggests.

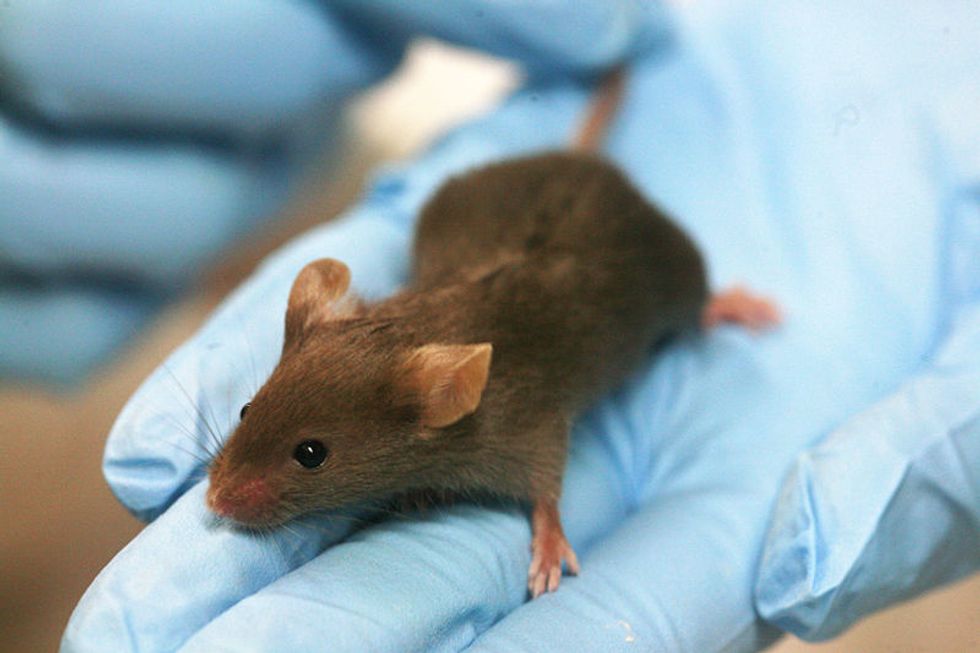

Male mice subjected to unpredictable stressors produced offspring that showed more flexible coping strategies when under stress, according to a study published online Tuesday in the journal Nature Communications.

The secret might be hidden in a small change in how certain genes are regulated in the sperm of the father and in the brains of offspring, the study found.

Several studies have shown that stress in early life not only can affect the individual’s behavior and cognitive functions, but can affect the next generation. So researchers have been eager to find any trace of changes in DNA coding that might underlie their observations.

Before you pen a “thanks for the resilience” Father’s Day card, consider: The study involved mice, not humans. More important, even the seemingly more resilient mice had lots of negative behaviors — depression and anti-social tendencies among them.

“If we look at the whole behavior of these animals, the benefit is really a very small proportion of the effects,” said study co-author Isabelle Mansuy, a neuroscientist at the University of Zurich’s Brain Research Institute. “Most other effects are fairly negative, because the animals are depressed, are anti-social, and have cognitive impairment.”

Researchers tried to mimic the effects of erratic parenting and a stressful home environment. So they separated male mouse pups from their mothers for several hours a day over the first two weeks of life, during which time they were occasionally restrained or forced to swim for five minutes — all at unpredictable intervals.

The mice then matured in social groups of four or five unrelated mice of the same sex that had equally unpredictable childhoods. Then they were matched to females, producing pups of their own. Once the pups grew up, they were subjected to various mazes that test the ability to show goal-oriented and flexible behavior under stress.

Compared with a control group, the offspring of stressed dads showed less hesitation in exploring an arm of a maze. And when offered the choice of getting a drink of water immediately or waiting for sugared water, the offspring of stressed males tended to wait for the greater reward. They also were better at figuring out changed rules — rewards that were moved from one spot to another, or cues that were changed.

Numerous studies of the effects of stress implicate a loop in the brain’s limbic system, which mediates emotion and causes the release of the stress hormone cortisol. That chemical can amp up a feedback loop to the brain.

Much of this stress-related reaction in the brain is mediated, in part, by a mineralocorticoid receptor, or MR, in brain cells.

The study found small changes in regulatory DNA sequences near an MR gene in sperm cells of the stressed mice. Such changes in gene regulation in response to the environment are known as epigenetic processes. The study found epigenetic markers associated with a half-dozen genes in the brain cells in the hippocampus of the offspring of stressed male mice.

Together, these changes offer a hint at a possible path for passing the effects of stress from one generation to the next.

Soldiers may offer a prime example, Mansuy said. “Many soldiers are people from lower socioeconomic environments and many of them have been exposed to violence, to broken families and to bad conditions when they were young,” she said. “And many of these people are stress-resilient, and they also have some adaptive advantages when they are placed in a situation of danger or challenge. They have developed coping strategies perhaps that other people have not.”

Still, she noted, these enhanced resiliency behaviors were “the only benefit” observed among the mice.

Researchers have been trying to untangle the effects of genetics and family background in post-traumatic stress disorder among soldiers returning from war.

Photo via WikiCommons