Watch Trump Fumble Meeting With Yazidi and Rohingya Refugees

Reprinted with permission from Alternet.

Amid outrage this week over President Donald Trump’s racist rhetoric and policies regarding asylum seekers and immigrants, critics expressed shock on Friday over two viral videos of the president meeting with several refugees from all over the world in the Oval Office.

One observer on social media accused Trump of displaying a “sociopathic inability to empathize” while another said “he couldn’t even manage to have a coherent three-minute conversation” with a Nobel laureate.

“You had the Nobel Prize?” Donald Trump learns of Yazidi activist Nadia Murad. Here’s how the interaction unfolded pic.twitter.com/DE3exTAm7N

— The National (@TheNationalUAE) July 18, 2019

https://twitter.com/Reaproy/status/1151848056566034438?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw%7Ctwcamp%5Etweetembed%7Ctwterm%5E1151848056566034438&ref_url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.alternet.org%2F2019%2F07%2Fwatch-trump-bumbles-through-meeting-with-refugees-and-humiliates-himself-with-uncomfortable-questions%2F

Trump appeared unaware of the plights of refugees like Nobel Peace Prize winner Nadia Murad, who has campaigned for human rights following her escape from ISIS captivity in Iraq, and Mohib Ullah, one of hundreds of thousands of Rohingya Muslims who were forced to leave Myanmar.

Murad explained how she and thousands of other women were abducted by ISIS when the group took control of parts of Iraq in 2014. The president has spoken frequently about his alleged defeat of ISIS in Iraq, but as Murad explained, “it’s not about ISIS” any longer.

“We cannot go back because the Kurdish government and the Iraqi government, they are fighting each other over who will control my area,” Murad said. “And we cannot go back if we cannot protect our dignity, our families.”

“I hope you can call or anything to the Iraqi and Kurdistan [governments],” she added, telling Trump that French President Emmanuel Macron has been vocal in his support for the Yazidis and their desire to return home.

Murad also spoke about what drove tens of thousands of Yazidis to seek asylum in Germany, as thousands of refugees are currently hoping to be welcomed into the United States while the Trump administration moves to eliminate asylum rights and considers cutting the number of refugee admissions to zero next year.

“After 2014 about 95,000 Yazidis, they immigrated to Germany through a very dangerous way,” Murad said. “Not because they want to be refugees, but we cannot find a safe place to live. All this happened to me. They killed my mum, they killed my six brothers.”

On social media, critics expressed shock at Trump’s apparent lack of knowledge and interest in the experiences of refugees around the world, even as he enacts xenophobic policies to keep them out of the United States.

Nadia Murad was one of thousands of Yazidi women and girls who were kidnapped and held by ISIS in Northern Iraq in 2014. Trump can't even turn to face her. pic.twitter.com/SF9cOhj8vx

— In the NOW (@IntheNow_tweet) July 18, 2019

Donald Trump says that he cares about combating sex trafficking, but he couldn't even manage to have a coherent three-minute conversation with Nobel Peace Prize laureate Nadia Murad, a trafficking survivor and global leader on ending sexual violence.pic.twitter.com/Mxd6tX9alP

— Simon Hedlin (@simonhedlin) July 19, 2019

Trump’s sociopathic inability to empathize is reflected in this embarrassing exchange.

-Nadia Murad: “They [ISIS] killed my mom, my six brothers”

-Trump: “Where are they now?”

-Nadia Murad: “They killed them. They’re in a mass grave in Sinjar”

-Trump: “I know the area very well” https://t.co/W3RKozxwOB— Karim Sadjadpour (@ksadjadpour) July 18, 2019

Some noted that Trump appeared engaged in his conversation with Murad mostly when he inquired about her Nobel Peace Prize, an award that Trump has said he hopes to win and which Murad was awarded for her work combating sexual violence around the world.

Trump doesn’t know who Nadia Murad is, doesn’t seem to care, doesn’t listen as she tells her horrific story, overhears her saying her family was killed – the only thing of interest to him is that she got the Nobel peace prize and he wants to know why pic.twitter.com/CuJhubVZRN

— Mathieu von Rohr (@mathieuvonrohr) July 19, 2019

Nadia Murad tells the president of the United States her heartbreaking story of having to survive genocide and mass rape and violence but Trump shows no compassion, interest or empathy, and only wants to know how and why she won a Nobel Prize. Sigh. https://t.co/HcMff534kP

— Mehdi Hasan (@mehdirhasan) July 19, 2019

Nadia Murad won the Nobel Prize for her horrific struggle with ISIS-the same ISIS Trump uses to scare his base. His reaction to her is a combo of jealous over a prize he wants and not really listening distain.

"They gave it to you for what reason?" pic.twitter.com/9xHWHZwVJG

— Amee Vanderpool (@girlsreallyrule) July 19, 2019

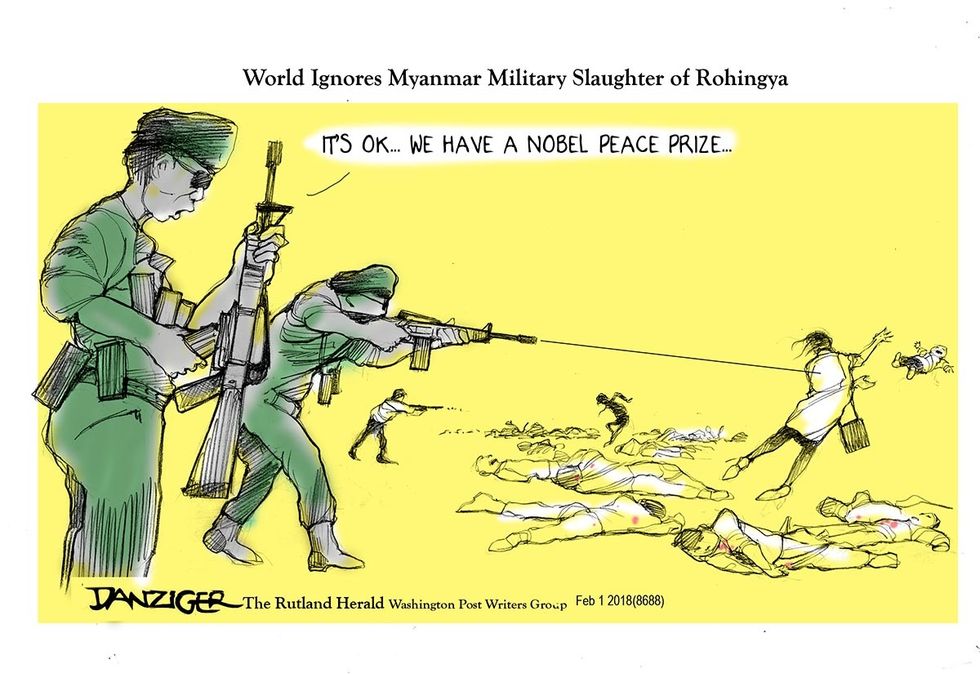

After speaking with Murad, Trump turned to Ullah, a member of the Rohingya religious group which was subjected to genocide in Myanmar in recent years. Ullah asked how the U.S. will help the Rohingya return to the country.

“Good afternoon, Mr. President,” said Ullah. “I am a Rohingya from Bangladesh refugee camp. So most of the Rohingya refugees are waiting to go back home as quickly as possible. So what is the plan to help us?”

After Trump asked Ullah what country he was from, Ambassador for Religious Freedom Sam Brownback quickly explained that the Rohingya have been expelled from Myanmar, but the president offered no answer to Ullah’s question.

This is the saddest thing I've seen in a long while. Rohingya man gets his chance to put a plea for help in front of the US president. Trump says "where's that?" Heartbreaking. What a desperate state we're in when world leaders don't instantly know about crimes against humanity https://t.co/0on22Tn7ey

— Nicola Smith (@niccijsmith) July 18, 2019

It’s possible that #trump’s ignorance about the plight of #Rohingya – even where they are from – will play into hands of those in #Myanmar who will use this to undermine their quest for recognition. Mind you, I doubt if he knows where Burma is. https://t.co/9eV7AmKuII

— Michael Vatikiotis (@jagowriter) July 19, 2019