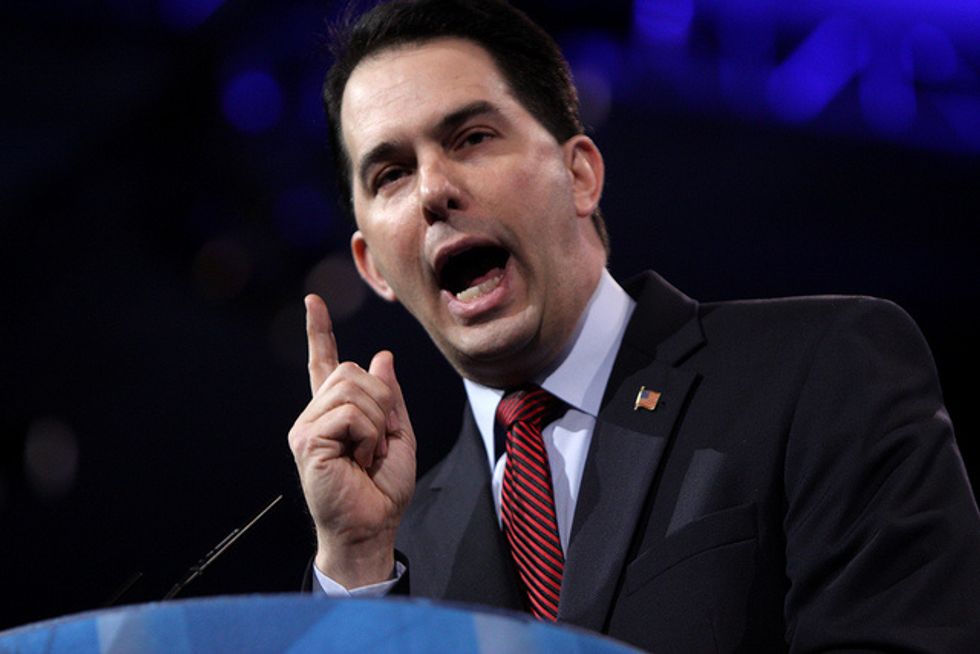

Scott Walker And The GOP Are Wrong About The Safety Net

It’s back and Democrats are going to have to deal with it. I’m talking about the political argument that they want to lure as many people as possible into government dependency.

This is a staple of Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker’s incipient presidential campaign, and he frames it as simple common sense. “Oftentimes when I think about the president and people like Hillary Clinton, I hear people who I think measure success in government by how many people are dependent on the government. By how many people are on food stamps and Medicaid and unemployment,” he said this week at the Florida Economic Growth Summit in Orlando. “I don’t know about all of you, but my belief in America is that we should measure success by just the opposite.”

Walker added: “I don’t remember any of my classmates saying to me ‘Hey, Scott, someday when I grow up, I want to become dependent on the government.’ Nobody signed my yearbook ‘Dear Scott, Good luck becoming dependent on the government.'”

Very funny, and a lot more appealing than Mitt Romney’s assertion that 47 percent of the electorate is dependent on government and will never take responsibility for themselves. The problem with Walker’s formulation, however, is that he’s creating straw politicians. President Obama and Clinton and practically everyone in their party — in fact both parties — talk incessantly about education, job creation, income inequality, and how to increase wages. That doesn’t sound like a yearning for Handout Nation. It sounds like people obsessing over how to make America a country of tubs standing on their own bottoms.

I’m not saying that Democrats haven’t given Republicans ammunition. The 2012 Obama campaign’s “Life of Julia” cartoon slideshow was a parody waiting to happen. From Julia’s enrollment in Head Start as a preschooler to her retirement aided by Medicare and Social Security, the sequence gave off a distinctly Soviet, cradle-to-grave vibe.

As pediatric neurosurgeon-turned GOP candidate Ben Carson put it in his announcement, “We’re not doing people a favor when we pat them on the head and say ‘there there, you poor little thing, we’re going to take care of all your needs. You don’t have to worry about anything.’ You know who else said stuff like that? Socialists.” That was less than a week after a real socialist — Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders — announced he was running for the Democratic nomination.

Obama came into office amid the worst recession since the Great Depression. The rolls of the three programs Walker named swelled as people lost jobs, income and health insurance. Job losses climbed to a terrifying 818,000 in January 2009, the month Obama was inaugurated. Another 2.2 million jobs were gone by the end of April. The unemployment rate was at or near 10 percent for eight months. So yes, there were a lot of people relying on government programs, for good reason. The private sector had completely failed them.

Obama’s chief economic message for years has been about sustained job creation and an unemployment rate nearly down to half its recession peak, not high enrollment in safety-net programs. Democrats do try to educate people about benefits for which they may qualify. But the goal is to get them on their feet, not lock them into dependency.

There is one area of government “dependency” that Obama and his party are proud of, and that is health insurance. The Department of Health and Human Services said this week that 10.2 million people bought private health coverage this year under the Affordable Care Act, and 85 percent of them receive federal subsidies to help pay for it. Millions more have been able to enroll in Medicaid as a result of the ACA expansion of the program to people with incomes slightly above the official poverty line. For those who believe health coverage should be universal, the numbers justify a victory lap.

People who receive insurance help, or food stamps or unemployment benefits, do indeed depend on the government — just like farmers, homeowners, corporations, and anyone else who receives subsidies or tax breaks, as well as companies that don’t provide health insurance or living wages. And just to be clear, if they are not children, disabled, or elderly, people who use the safety net often have jobs. Nearly 43 percent of all food-stamp recipients live in a household with earnings, according to the Department of Agriculture. The Kaiser Family Foundation, in a study of states that haven’t adopted the Medicaid expansion, found there are workers with full- or part-time jobs in 66 percent of the families eligible for it.

Jeb Bush has called the safety net “a spider web that traps people in perpetual dependence.” We are going to hear a lot of statements like that in the next 18 months. But that doesn’t make them true.

Follow Jill Lawrence on Twitter @JillDLawrence. To find out more about Jill Lawrence and read features by other Creators Syndicate writers and cartoonists, visit the Creators Syndicate website at www.creators.com.

Photo: Gage Skidmore via Flickr