Girl Meets German Stem Cell Donor Who Helped Her Beat Cancer

By Sarah Freishtat, Chicago Tribune (TNS)

CHICAGO — Sabrina Chahir was waiting to meet the man who helped send her cancer into remission. The 8-year-old girl, who likes art and takes piano lessons, knew he had flown across an ocean to see her, nearly four years after he donated his stem cells to help rid her blood of cancer that could have taken her life.

Recently Sabrina and Maximilian Eule, 30, had their first face-to-face meeting at a celebration in suburban Schaumburg with Sabrina’s friends and family.

The two had emailed and video-chatted. But Sabrina’s mother, Natalia Wehr, said it was important to her to meet Eule in person.

“It’s your daughter, and this person we don’t know did something so wonderful,” Wehr said. “You need to know who that is.”

Sabrina was diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia, one of the most common types of cancer in children, when she was 2 1/2. The cancer cells were in more than 80 percent of her blood.

The girl’s cancer had gone into remission before, but she soon relapsed. After rounds of treatment and infections that caused Sabrina to go blind temporarily, doctors at Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago told Sabrina’s family she would need a stem cell transplant.

“It was the most painful thing you can imagine,” Wehr said. “Not knowing if your child is going to live or not. It’s the worst feeling in the world.”

Ten to 15 percent of children diagnosed with this type of leukemia need a stem cell transplant, but the treatment is more common for other types of cancer, said Dr. Reggie Duerst, one of Sabrina’s doctors and director of the stem cell transplant program at Lurie.

And while doctors said the best donor matches are often people of similar racial and ethnic backgrounds — Sabrina is Hispanic and Arab — her match, located through a computer database, turned out to be a German man who lives in Austria.

Wehr spent about 10 days waiting, hoping and praying before she learned Eule had agreed to become her daughter’s donor.

Eule, who paid out of pocket for his trip to America for the meeting, said he almost cried when he was told he could donate stem cells to a little girl.

He had registered as a prospective donor when a man in his village became ill, he said. Though he wasn’t a match for that man, he said he was happy he was paired with Sabrina.

“Sabrina became a part of myself,” he said.

Eule had to wait at least a year to contact Sabrina and her family, under donation rules. Then, both sides must agree to meet.

On a recent evening, in a private room of Pilot Pete’s Restaurant & Bar at the Schaumburg Airport, Sabrina waited for Eule’s arrival, wearing a fancy red party dress.

When he walked in, she jumped up, ran to him and threw her arms around him. Eule, looking a bit overwhelmed at the row of TV cameras and lights, said he “can’t find the right words” to describe what he was feeling.

The two vowed to remain in touch and exchanged gifts. Eule gave Sabrina a necklace “so you always have something from me with you.” Sabrina’s family gave her donor a watch on which they had engraved: “Time passes, memories fade, but hearts never forget.”

Moved by the other gift Eule gave Sabrina — the chance to live into adulthood — Sabrina’s cousin also registered to become a donor at a drive her family organized to help find a match for a friend.

The cousin was soon paired with a patient and donated stem cells to her twice.

“That was pretty amazing,” Wehr said. “That we were able to live this from both sides.”

Though Sabrina is in remission, the hospital plans to follow her progress throughout her life, Duerst said. It is important to re-educate young patients about what they went through, and track any complications or illnesses in her future, he said.

Sabrina doesn’t like to talk about losing her hair during treatment or look at pictures of herself from that time, Wehr said.

But she talks about wanting to be a chef when she grows up. If that doesn’t work out, maybe she’ll become a ballerina, Wehr said.

“Now’s the time to celebrate that everything went well,” she said.

(c)2015 Chicago Tribune, Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC

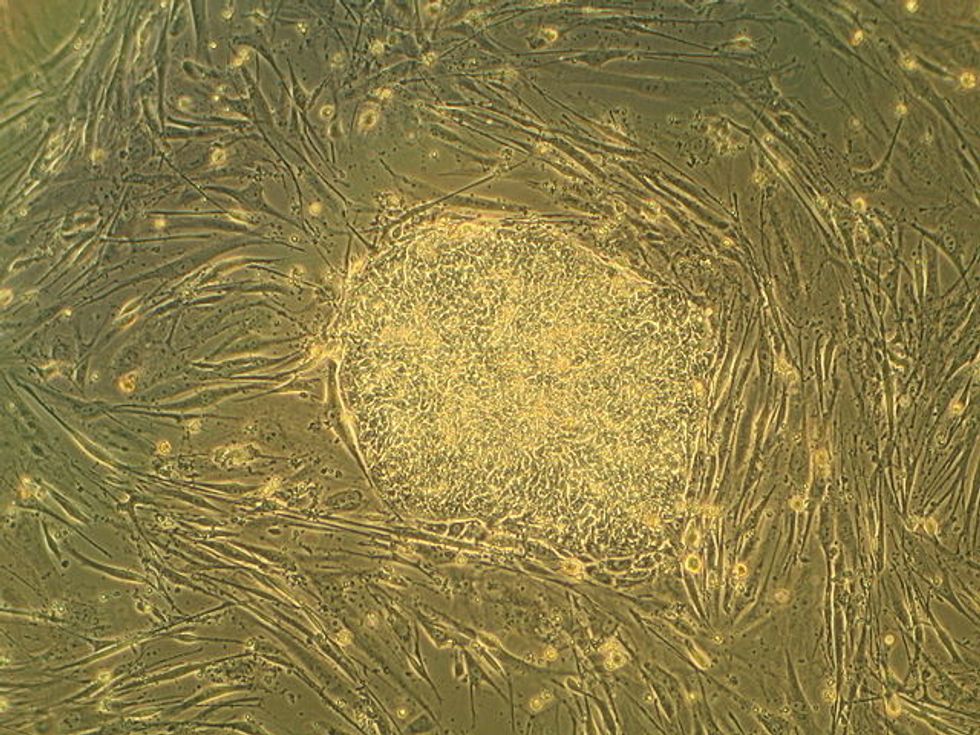

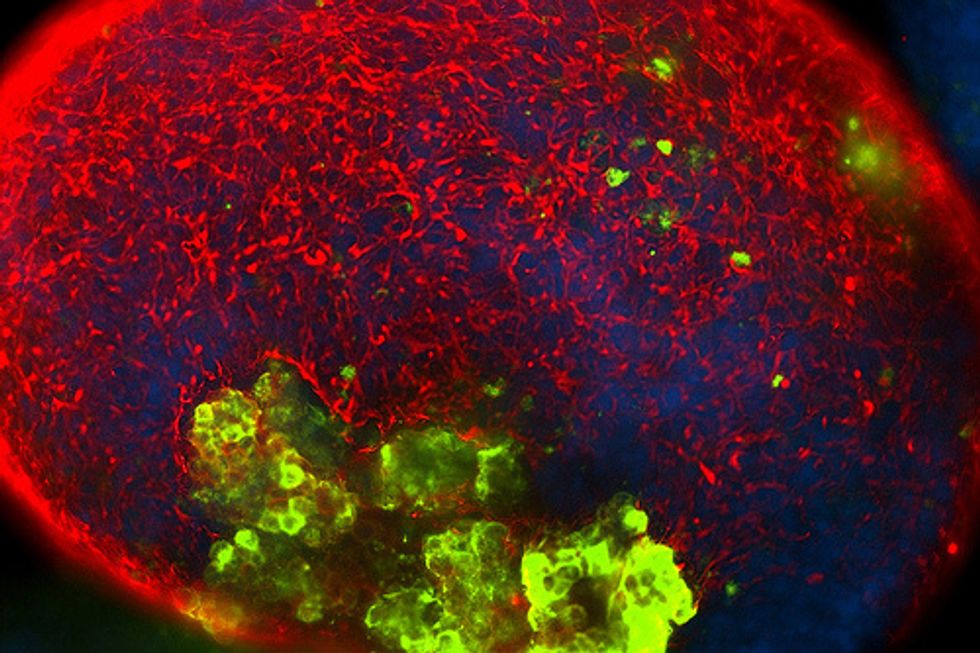

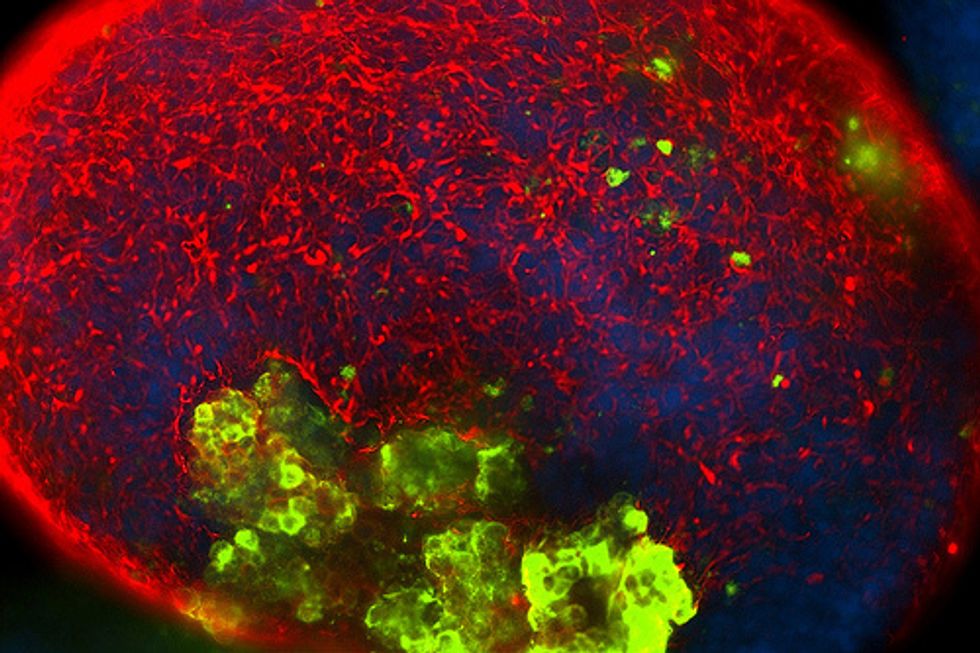

Photo: A colony of embryonic stem cells, from the H9 cell line (NIH code: WA09). Viewed at 10X with Carl Zeiss Axiovert scope. (The cells in the background are mouse fibroblasts cells. Only the colony in the center are human embryonic stem cells). Via Wikicommons