Can Democrats Win The Senate In 2016?

By Stuart Rothenberg, CQ-Roll Call (TNS)

WASHINGTON — For Republicans, the fight for control of the Senate in 2016 is all about playing defense.

Unlike 2014 (and 2018), the Senate races of 2016 offer few, if any, opportunities for the GOP as the election cycle begins. The map strongly favors Democrats and suggests the possibility of considerable Democratic gains.

Republicans hope to recruit strong challengers to Democrats Michael Bennet of Colorado and Senate Minority Leader Harry Reid of Nevada, but the other eight Democratic senators up next year come from states so reliably Democratic that Republicans don’t have any real hope of making them competitive.

On the other hand, Republicans are defending 24 seats, including seven that gave their electoral votes twice to President Barack Obama, and another two (Indiana and North Carolina) that were carried by Obama in 2008, but not 2012.

Some of the GOP seats that went for Obama twice are prime Democratic opportunities — Illinois, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, for example — while others remain only mouthwatering possibilities for now. How they will develop will depend on the quality of Democratic recruiting and other factors.

Democrats will need to net five seats to win a Senate majority in 2016, but they could win control by adding only four seats (getting to 50) if the party holds the White House for the third straight election.

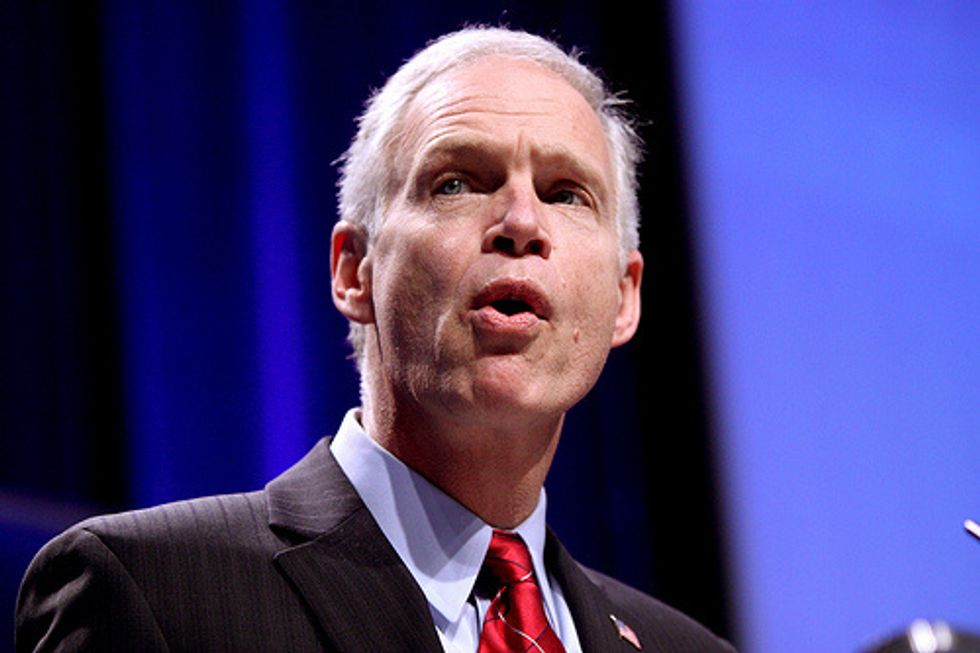

Based solely on fundamentals, three Republicans in the “bluest” states of the cycle start out at the greatest risk: Mark S. Kirk in Illinois, Patrick J. Toomey in Pennsylvania and Ron Johnson in Wisconsin.

All three states voted for the Democrat in at least each of the past six presidential contests (Wisconsin went Democratic in the past seven). They are also large, populous and expensive states for campaigns.

Size and population are important because candidates have a hard time localizing races in those kinds of states. A hopeful simply can’t meet a lot of voters and has to rely on statewide, or in the case of the presidential race, national, messaging.

Kirk and Toomey squeaked by their Democratic opponents in 2010, a remarkable Republican year, while Johnson had a somewhat easier time defeating veteran Sen. Russ Feingold. But it’s unlikely any of the Republicans would have won in anything approaching a neutral political environment.

Even if those three Republican senators lose, Democrats would need at least one more victory, and possibly two. That won’t be easy.

The next group of vulnerable Senate Republicans includes Marco Rubio in Florida, Kelly Ayotte in New Hampshire and Rob Portman in Ohio, all of whom hail from swing states. Obama carried their states twice, though his margins in Florida and Ohio were razor-thin.

Obama’s performance in New Hampshire in 2008 and 2012 was almost identical to his performance in Pennsylvania, but the Granite State is much smaller, and retail campaigning is easier there. Just as noteworthy, while Toomey squeaked by his Democratic open-seat opponent in 2010, Ayotte annihilated her Democratic opponent in her open-seat race.

Three other Republican seats should be on everyone’s radar, though they aren’t nearly as competitive as the six already mentioned.

Recent presidential and Senate races confirm North Carolina has become competitive, so Sen. Richard M. Burr bears watching. And Sens. Charles E. Grassley of Iowa, who will turn 83 before his next re-election, and John McCain of Arizona, who will turn 80 in September of 2016, can’t be ignored.

One huge unknown about 2016 involves the presidential race.

There have been a few cases where a strong presidential victory by the non-incumbent party also swept in a large number of senators from the incoming president’s party. The two most obvious recent examples are 1980 (Ronald Reagan) and 2008 (Obama), when “change” elections filtered down to House and Senate races.

But there are plenty of other cases where a presidential victory didn’t result in notable Senate gains. Republican George W. Bush won the White House (though not the popular vote), but Democrats added four Senate seats in 2000. Democrat Bill Clinton was elected president in 1992 (in a three-way race), but Democrats gained no Senate seats. (All data from Brookings’ Vital Statistics on Congress, tables 2-3 and 2-4.)

In 1976, Democrat Jimmy Carter won the White House running as a messenger of change, but neither party gained Senate seats that year. And in one of the more remarkable outcomes, Republican Richard M. Nixon was re-elected in a landslide in 1972, but Democrats added two Senate seats.

In the single case over the past 60 years when one party held the White House for three consecutive elections, the GOP in 1988, Democrats gained one Senate seat.

Large net Senate swings (of five seats or more) obviously depend on the partisan makeup of each class, but it is also clear that they are more likely to occur during midterm elections (for example, 2014, 2010, 2006, 1994, 1986 and 1958) than in presidential years.

Presidential year dynamics differ from midterm dynamics in one important way: Unlike midterm elections in states with Senate races, voters in presidential cycles have two votes — one for the president and one for the Senate. That gives them the freedom to make two very different statements.

In 2012, six states selected a senator from one party and a presidential nominee from another: Indiana, Missouri, Montana, Nevada, North Dakota and West Virginia.

In 2008, seven states voted for one party’s presidential nominee but the other party’s Senate nominee: Alaska, Arkansas, Louisiana, Maine, Montana, South Dakota and West Virginia.

This cycle, the Senate map, historical turnout patterns in presidential years (which favor Democrats) and the division within the GOP create enough good opportunities for Democrats to win at least three and as many as six seats.

But parties don’t always take advantage of opportunities, and Democrats will have to work hard to flip the Senate in a presidential year.

Photo: Gage Skidmore via Flickr