By Alfredo Corchado, The Dallas Morning News

HUEHUETOCA, Mexico — After more than three weeks of silence, The Beast growled again, blew its whistle, and finally left Tenosique, Mexico, near the border with Guatemala. Heading north, the train took on hundreds of Central Americans as shelters emptied along the way, from Veracruz to Puebla.

Held up for weeks by the Mexican government, and after pressure from the Obama administration, the freight train was running again. But many on board were having second thoughts about continuing on to the United States.

By the time the freight train reached Mexico City and a migrant shelter in the state of Mexico, many had gotten off. The journey had become more perilous. The border with Texas seemed more distant, unwelcoming, and unreachable. Instead, the migrants hoped to find jobs at the booming aerospace and auto plants in central Mexico.

“They’re in the eye of the storm,” said Ruben Figueroa, an immigration activist at a shelter in Tenosique and a former immigrant who once worked in North Carolina. “As always, their future — our future — is tied to U.S. electoral politics.”

In recent months, Central American migrants, including 63,000 unaccompanied minors, have streamed across the U.S. border, mostly in South Texas. The flow has intensified debate among Americans about migrants from Central America, who for decades have made the trip north to enter the United States illegally by stowing away atop freight trains.

Last month, I traveled for four days along some of southern Mexico’s busiest migrant routes.

By car and bus, I followed the path of The Beast, so named because of the many migrants killed or maimed beneath its wheels. I continued along the route, watching The Beast zip through Central Mexico, from Puebla to Mexico City and the states of Mexico, Guanajuato, and Queretaro. I talked to migrants on their way to Arizona and California, as well as entry points on the Texas border by way of Ciudad Juarez or Reynosa.

The barriers — from increased vigilance on both sides of the border to exploitation by criminals — had intensified, pushing some to take drastic measures.

Huehuetoca

At a shelter in Huehuetoca, just outside Mexico City, Jaime Eduardo Gonzalez of Guatemala has decided to travel with a new companion: a 22-inch machete.

“Many of us travel alone, accompanied only by God,” he says, wrapping the machete with clothes and tucking it into his tattered suitcase. “These days, carrying a machete also helps.”

He says he uses the machete to clear brush as he walks parts of the country on foot, away from the watchful eyes of Mexican authorities. But he also keeps it to protect himself. Gonzalez, 20, says he was held against his will by a criminal gang in the state of Veracruz, and was nearly killed when he escaped.

“There are some bad people along the way,” he says.

Now, with machete in tow and fear in his eyes, he plans to reach Los Angeles, where his mother and brother live.

Ever Javier Melendez, 20, is heading in the opposite direction. Originally bound for the United States from his home in La Ceiba, Honduras, he had made it as far as San Luis Potosi state. There, members of the criminal group known as the Zetas took all his money and documents, even a letter he carried with a phone number for relatives in case he died.

“They wanted me to work for them, help them with the smuggling business,” he says. “They slapped me around with a gun and then put it to my head. I agreed, but on the first opportunity, I ran away and caught the train south.”

El Bajio

The railroads cut through Queretaro state on their way north or northwest, not far from rural communities like Pozos, San Luis de la Paz, and on to San Luis Potosi. They pass through a region thriving economically, where factory workers build cars, airplanes, and refrigerators in new factories, and fields of tomatoes, broccoli, and lettuce stretch for miles.

Almost one-third of Mexico’s automobile manufacturing industry is based in Queretaro, and the state is expanding into the burgeoning aerospace industry with more than 33 companies.

Lucas Anderson and Wilmer Lopez walk along 5 de Mayo Street and inquire at a coffee shop about possible jobs. The owner politely shakes his head and suggests they try factories in the outskirts of the city instead. “There is always work there,” he says.

Later, he confides, “They say they’re Mexicans, but you can tell in an instant they’re Central American.” The cafe owner prefers not to give his name, fearful that extortionists may target his business.

I catch up to the two men. They tell me they’re from Mexico. I was just in Honduras, I respond. “I loved your country,” I say. They look sheepish.

Yes, they say, they’re from Honduras and they’re looking for temporary jobs before they can continue on their journey to Texas, where they have family and friends in Galveston.

“We still want to get to Texas,” says Anderson, 20.

“But it’s not a good time, so we’re looking for a job, anything,” adds Lopez.

I ask what has changed about the trip through Mexico. “Everything,” Anderson says. “It’s like crossing the United States, with so much security, technology, and, worse, criminals hunting us down as though we’re animals.”

El Paso

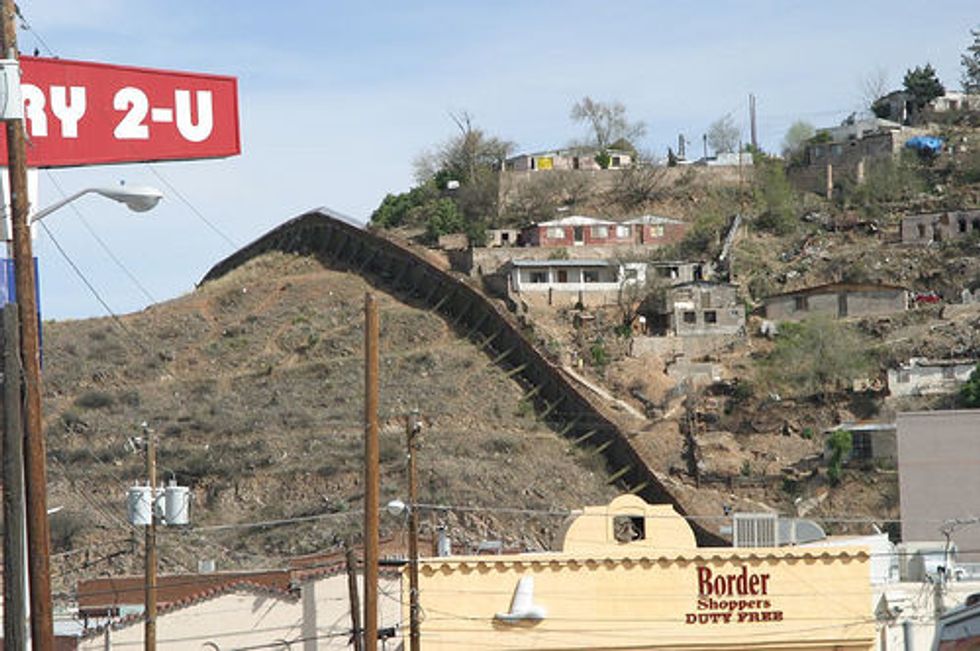

In Ciudad Juarez, The Beast ends its journey. A new journey begins on the U.S. side in places like El Paso, known as the Ellis Island of the Southwest.

The flow of migrants from Central America, U.S. authorities say, is slowly inching from the Rio Grande Valley toward El Paso.

Attorney Carlos Spector has practiced immigration law for more than 30 years. In recent years he has represented Mexicans fleeing violence in their country, so many that he has a weekly radio show called “La Hora del Exiliado” (The Exile Hour). He recently picked up five new asylum cases — all Central Americans.

He suggests that the U.S. involvement in Central America’s wars during the 1980s helped plant the seeds for the instability and turmoil there today.

“Whenever the United States tries to use military force, or meddle in internal affairs, as it did in Central America in the 1980s, there will be consequences that are no different than, say, Iraq or Afghanistan,” he says. “The chickens have come home to roost.”

Photo: Cronkite News Service/MCT/Jessie Wardarski

Interested in world news? Sign up for our daily email newsletter!