It all began so promisingly. Young Richard Holbrooke, a gangly 21-year-old graduate of Brown, joined the Foreign Service in 1962, inspired by the idealism of President John F. Kennedy. The State Department assigned him to the rural southern tip of Vietnam. In a region where the South Vietnamese army and its American advisers claimed to have eliminated the communist guerrillas, Holbrooke discovered the Viet Cong were actually pervasive and getting stronger. Observant, clever, and energetic, Holbrooke was an early witness to the collective delusions driving the U.S. war in Vietnam.

Holbrooke dodged bullets and filed reports. He sniffed the breezes of the U.S. embassy where American ambassadors and generals thought they could shuffle local leaders to achieve the victory they assumed was inevitable. He didn’t know all the American men had Vietnamese mistresses. He didn’t quite get the menace of the Quiet American, the prototypical interloper of Graham Greene’s novel, whose blind desire to do good has bloody consequences. But in his lucid letters and reports, Holbrooke conveyed the awful reality that the United States—his government—was inflicting catastrophic violence on a country it barely understood.

Holbrooke dreamed of doing good by doing better. Upon his return to Washington, he dedicated his brain and body to becoming secretary of state (or national security adviser) in the pretentious Great Man mold of Henry Kissinger and Zbigniew Brzezinski. He schemed and seduced constantly, all while maintaining a constant presence in Washington policy discussions. In every presidential election year from 1984 to 2008, Holbrooke was touted as a leading contender for secretary of state in the next Democratic administration.

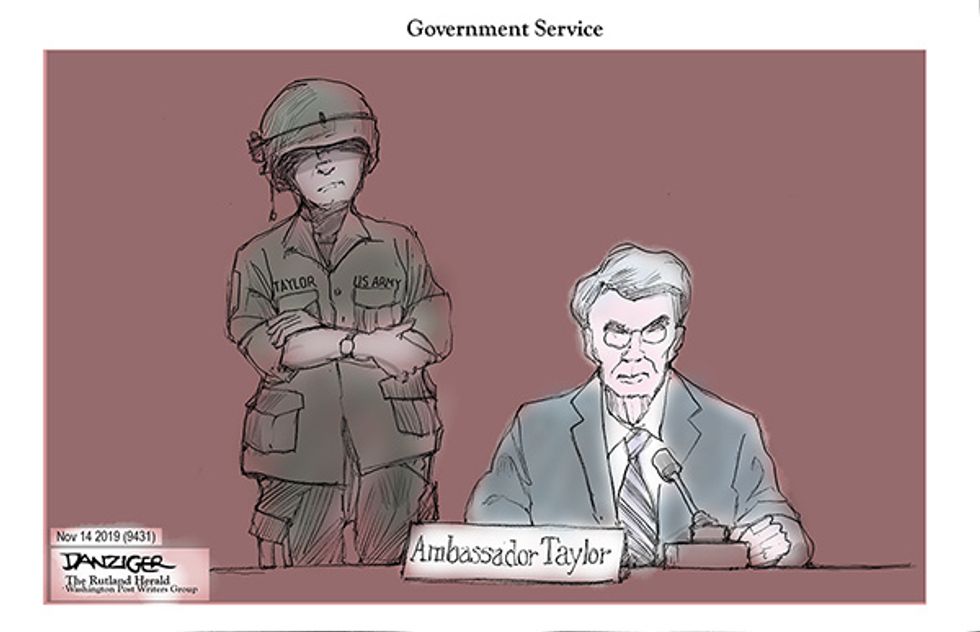

Brilliant and abrasive, Holbrooke aspired to the peak of power but never quite summited. In his last assignment as special envoy to Afghanistan, he hoped to salvage a historic peace agreement. President Obama never gave him the chance. The Afghan war was still droning on when he died in 2011.

Holbrooke is the verbose, lucid, obsessive, tricky, but not quite tragic hero of Our Man, George Packer’s endlessly engaging biography. A former New Yorker staff writer, Packer unspools Holbrooke’s story as a rich and sinuous tale of American Exceptionalism, the problematic—if not demonstrably false—notion that America is uniquely endowed to steer the affairs of the entire planet.

Packer is acute on the realities of Holbrooke’s ambition—the narcissism, mendacity, and vanity that powered it. He does not flinch from its cost to females, friends and family. Our Man is not a case study in the exercise of American power. It is a cautionary tale about the manic pursuit of it.

It is also essential reading for the thundering herd of 2020 Democratic presidential candidates as they begin to define themselves on issues of war and peace. The next Democratic president will have to assemble a national security team and manage a global military empire. Holbrooke’s career illuminates how the last three Democratic presidents—Carter, Clinton, and Obama—handled this challenge, while accommodating and deflecting his ambitions. Holbrooke’s legacy, it turns out, is one Democratic presidents have preferred to avoid.

Packer is the sympathetic pal kind of biographer. At the outset, he warns that his biography will favor character over history, the personal over the political, and so it does. He was friends with Holbrooke and mixed with his social set. He makes no apologies for his access to his subject and seems aware of its inevitable costs. He wastes no time on Holbrooke’s childhood, barely mentions his parents and jumps right into his pursuit of power.

Holbrooke was appalled by what he had seen in Vietnam and the refusal of President Richard Nixon to de-escalate. He left the Foreign Service in 1969. He became editor of Foreign Policy, a new quarterly policy journal and rival to the stuffier Foreign Affairs. Writing and editing articles kept his name and ideas in circulation while President Nixon was self-destructing and Gerald Ford lost the 1976 presidential election to Jimmy Carter.

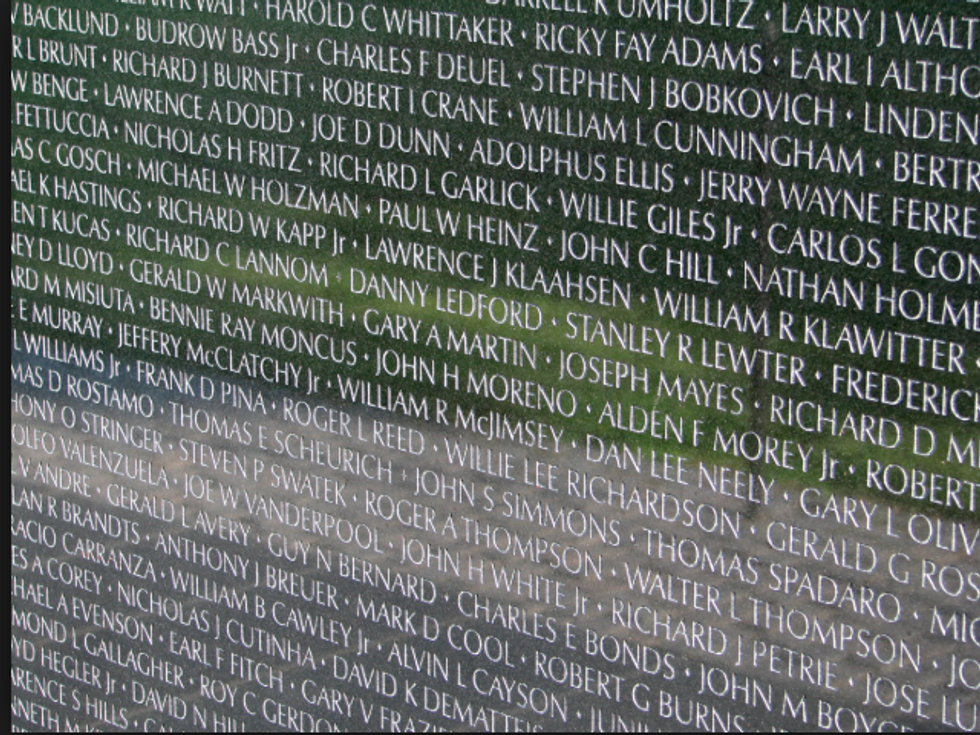

In 1977, Carter appointed Holbrooke as assistant secretary of state for Asia. Packer highlights one of Holbrooke’s real accomplishments: securing the admission of some two million refugees from Vietnam into America in the late 1970s. Packer doesn’t even have to mention current events on the Mexican border to say the Carter-Holbrooke policy “shames us today.”

He does not dally on Holbrooke’s diplomacy in Indonesia, where the government was waging a scorched earth campaign against rebels in the breakaway province of East Timor. On a visit in April 1977, notes historian Brad Simpson at the non-profit National Security Archive, Holbrooke “offered no criticism of Indonesia’s human rights record while ‘acknowledging efforts President Suharto appeared to be making to resolve Indonesian problems,’ especially on East Timor, where he ‘applauded’ the President’s judgment in allowing Congressional members to visit the territory but remained mute on reports of ongoing atrocities.”

Packer mentions only in passing another lesser milestone in Holbrooke’s career: the Gwangju massacre in South Korea in May 1980. At the time, South Korea was ruled by an unstable and unseemly fascist dictatorship. The chief of the Korean CIA had recently assassinated his boss, the president, during a very unpleasant office meeting. The dictatorship was trying to consolidate itself while a popular movement rallied in the streets for the restoration of democracy. A grassroots movement took over the southern city of Gwangju, a university town known for its independent ways. After the Korean armed forces slaughtered some of the unarmed demonstrators, U.S. policymakers were apprised that elite military units were mobilizing to finish the job.

Here was a life and death test of the lessons learned in Vietnam: How far should the U.S. government indulge a repressive ally? Where to draw the line? At a White House meeting in May 1980, President Carter decided, with Holbrooke’s concurrence, that they had to let the Koreans “maintain law and order.” The last protesters were massacred. Holbrooke kept quiet while privately seeking to save dissident leader (and future president) Kim Dae-Jung from execution.

Packer gives Holbrooke a pass on East Timor and Gwangju. Human rights considerations are inevitably sacrificed to national interests, he avers. The American ideal of promoting human rights is impossible to achieve. “Be unhappy when senior officials fail to live up to it,” Packer writes. “Just don’t be surprised.”

If the point is that the real world sometimes offers excruciating trade-offs between security and human rights, Packer is surely right. It is less obvious that Holbrooke made the right choice. The threat of a North Korean attack was more a pretext than a reality. The South Koreans were in no position to buck a pre-emptive warning from Washington to stand down. Holbrooke didn’t speak up, and hundreds of people were killed. Gwangju has never forgotten, even if Washington has.

The lesson for 2020 Democrats? U.S. rhetoric about human rights will never be credible—especially in the wake of Trump’s embrace of dictators everywhere—unless the next president is willing to back human rights rhetoric with action to protect democratic forces.

Holbrooke’s idealism had evolved into realism, if not cynicism. He had acquiesced, Packer notes, to an ironic reality of post-Vietnam national security politics in Washington. Policymakers, like Holbrooke, who recognized the folly of the Vietnam war and warned against reflexive military interventions would forever suffer from the reputation of being “soft.” The hawks who favored futile escalation were rewarded with a reputation for toughness.

The 2020 Democrats, candidates and voters alike, need to understand this pernicious dynamic is still at work in Washington, where the intellectual authors of the Iraq fiasco are considered as credible as the critics who predicted it. The next Democratic president need not make that mistake.

Holbrooke’s policy legacy is not easy to discern. In the fiercest Washington policy debates of the 1980s, Holbrooke was more notable for his absence than his presence. He barely figured in the two most contentious issues of the day: the bloody civil wars of Central America (which most Democrats wanted to stay out of) and the nuclear freeze (which Democrats and many independents favored). Over the course of the decade, these controversies mutated into the Iran-contra scandal and the end of the Cold War. In these events, Holbrooke offered no special insights or even much involvement.

Packer covers this period in Holbrooke’s life from 1980 to 1992, the Reagan-Bush era, with a breezy style in barely 30 pages:

The scene shifted to New York, just as the Wall Street carnival was getting started. He made money for the first time and acquired a new roster of friends, more chiefs than Indians because that’s how it goes when you rise with age. Girlfriends—of course! For all the hot lights of Manhattan, you’ll find that during stretches of the eighties he grows indistinct—the very glare of the camera starts to blur the man. But the interior light in that sleepless brain never dimmed. The whole time he was positioning, connecting, learning, expanding, surveying, getting ready for the only thing that really mattered.

Namely, his own return to power.

A more analytical biographer might have compared Holbrooke’s career to his contemporary Elliott Abrams, another national security operator on the rise in the 1980s. While Holbrooke was getting rich from a Wall Street sinecure, falling in love with high-powered women, and plotting his return to power, Abrams was making policy for the hawkish cabal around President Reagan.

Abrams defended the death squads of El Salvador. He brokered secret deals for the CIA-trained contras in Nicaragua. Packer’s character-driven narrative only occasionally glances up at the larger political landscape or its implications. Unlike Abrams, Holbrooke had no mission larger than fulfilling his own genius, following “the interior light in that sleepless brain.” Abrams embraced the impunity of the empire; Holbrooke embraced its privileges. Abrams is still around, modus operandi unchanged.

The election of Bill Clinton in 1992 delivered a Democrat into the White House. Alas, it did not deliver Holbrooke to the seat of power. Clinton didn’t much care about foreign policy, and he didn’t need an aspiring Great Man to run the State Department. The dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 had left America without a dangerous enemy, a luxury the next president won’t have. Clinton (and First Lady Hillary) preferred to pursue a national health care plan and put foreign policy on autopilot. Clinton chose an unimaginative lawyer, Warren Christopher, as his secretary of state.

In 1994 Holbrooke caught a break. Clinton gave him a thankless assignment beyond Christopher’s limited skillset: negotiate an end to the vicious ethno-nationalist bloodletting in Bosnia. Over the course of a grueling year, Holbrooke coaxed the Balkan leaders into a peace agreement. Along with the admission of the Vietnamese refugees, the Dayton Accords was a genuine accomplishment. Few others in the U.S. government could have pulled it off, and he probably saved thousands of lives.

The rewards were few. Clinton contemplated promoting Holbrooke but backed off. The Nobel Prize Committee didn’t give him a Peace Prize, perhaps because the NSC memorandum documenting his acquiescence in the Gwangju massacre became public in 1994.

In time, Holbrooke became a prisoner of the same sort of Washington orthodoxies that he had once seen right through. After 9/11, he supported President Bush’s campaign to invade Iraq. He urged aspiring Democratic presidential contenders John Kerry and Hillary Clinton to do the same.

“Vietnam had taught him again and again that a soft Democrat was politically doomed,” Packer writes.

The supposedly savvy Holbrooke was dead wrong. Kerry and Clinton voted for the war, and they wound up with the scarlet letter “I” forever stamped on their foreheads. (Packer admits he made the same mistake, “stupidly” and “disastrously” endorsing Bush’s war.) In the same period, an unknown state senator named Barack Obama opposed the war on principle and gained a reputation for prescience and prudence that helped propel him to the White House. There’s a lesson for the 2020 presidential aspirants.

The last chapter of Holbrooke’s career, as special envoy to Afghanistan, verges on the pathetic. The realities of U.S. intervention in Afghanistan echoed Vietnam in every way: the impermeable local culture, the feckless and corrupt allies, the overweening American ambassadors, and the generals’ self-serving reports of “progress.”

Yet the mature Holbrooke repeated all the mistakes he dissected as a young man. He managed to alienate his boss, Obama, and his host, Afghan president Hamid Karzai, while getting patronized by White House staffers and ultimately rolled by Gen. David Petraeus, who squelched his dreams of a peace agreement. In his last hurrah, he achieved nothing but his own marginalization. And he would emerge from meetings clueless, telling aides, “[that] went well.”

Packer’s epitaph for Holbrooke’s career is an epitaph for American Exceptionalism and for the wars it generates:

By the end he was living in each chapter of his life simultaneously—Kennedy and Obama, Vietnam and Bosnia and Afghanistan—as if he were floating in a single body of water whose temperature varied from place to place and depth to depth. All that accumulated experience—we Americans don’t want it. We’re almost embarrassed by it, except when we’re burying it. So we forget our mistakes or recoil from them, we swing wildly between superhuman exertion and sullen withdrawal, always looking for the answers in our own goodness and wisdom instead of where they lie, out in the world, and in history. I’m amazed we came through our half century on top as well as we did. Now it’s over.

What comes next is the question that the 2020 Democrats, candidates and voters alike, need to answer in the next 17 months. The United States is waging war in four theaters (Syria, Afghanistan, Somalia and Yemen) while maintaining a uniformed military presence in 149 countries. President Trump has trashed the State Department, traditional alliances, and multilateral institutions. He has replaced diplomacy with bluster and transactional deals.

The belief that America is uniquely endowed to do good sustains this global empire and energizes Trump’s bullying “regime change” rhetoric in Venezuela and Iran. It is a myth that should be buried. After the trillion-dollar failures of Afghanistan and Iraq and the incoherent transactionalism of Trump, the next president has to find a foreign policy that is less reckless and more focused on the well-being of the American people.

For better and worse, the accumulated experience of Richard Holbrooke is a good guide to what should be embraced and avoided. As his very best, Holbrooke showed the United States could serve as an honest broker pacifying the international system. At his more common worst, he enabled the violent illusions of American Exceptionalism.

The 2020 Democrats, meaning both candidates and voters, can do better. The Americans who resisted the brutal proxy wars of Central America in the 1980s (that yielded the failed states of today) did not assume American wisdom and goodness. They questioned it. Those who warned against the folly of Iraq and Afghanistan in the 2000s did not bury the experience of the past. They pushed it to the fore and were ignored by the likes of Packer. They knew the sell-by date of the doctrine of American Exceptionalism had expired long before Richard Holbrooke.

Jefferson Morley is a writing fellow and the editor and chief correspondent of the Deep State, a project of the Independent Media Institute. He has been a reporter and editor in Washington, D.C., since 1980. He spent 15 years as an editor and reporter at the Washington Post. He was a staff writer at Arms Control Today and Washington editor of Salon. He is the editor and co-founder of JFK Facts, a blog about the assassination of JFK. His latest book is The Ghost: The Secret Life of CIA Spymaster, James Jesus Angleton.

This article was produced by the Deep State, a project of the Independent Media Institute.

IMAGE: The official State Department photo portrait of Richard Holbrooke, dated November 5, 2009.