By Jim Puzzanghera and Don Lee, Los Angeles Times

The nation’s poverty rate dropped last year for the first time since 2006, but the typical household income barely budged in a sign of the continuing sluggish economic recovery from the Great Recession, the Census Bureau said Tuesday.

The decline in the poverty rate to 14.5 percent of the population from 15 percent in 2012 was driven by an increase in people with full-time jobs last year, Census officials said.

The number of people working full time rose by about 6.4 million to 105.8 million last year. The increase included nearly a million households with children under 18 years old.

That rise helped lead to the first drop in more than a decade in the child poverty rate, which fell to 19.9 percent last year from 21.8 percent, the Census Bureau said.

The last time the child poverty rate dropped was in 2000.

“We are seeing that the economy is certainly having an impact on that group,” said Chuck Nelson, a division chief at the Census Bureau.

But the news was not all good.

Despite the decrease, the poverty rate last year remained two percentage points higher than in 2007, before the Great Recession started.

And because of population growth, the number of people living in poverty did not improve significantly for the third straight year.

There were 45.3 million people living below the poverty threshold, which last year was an annual income of less than $23,624 for a household with four people, including two related children.

In 2012, about 46.5 million people were living below the poverty line.

Median household income last year rose to $51,939, up only slightly from $51,759 the previous year. It was the second year median income was roughly flat after two straight declines, the Census Bureau said.

Adjusted for inflation, median household income was 8 percent lower than it was in 2007.

Latinos were the only ethnic group to experience a significant increase in median household income last year. Their median income rose 3.5 percent to $40,963, the Census Bureau said.

With lower-earning families seeing significant gains, the disparity between the highest-income and lowest-income households showed no significant change from 2012 to 2013.

But the gap, which has been widening in recent decades, remains substantial.

The top 5 percent of households last year garnered more than 22 percent of all income in the country, and the top 20 percent accounted for more than half of all the money earned. The share of income that went to the bottom 60 percent of households was just 26 percent.

By age group, the Census figures show there were significant income gains only for the youngest and oldest households.

Income for households headed by 15-to-24-year-olds jumped 10.5 percent in 2013 from the prior year, reflecting the increase in young people getting full-time jobs. In homes of those 65 and older, income went up 3.7 percent, helped by inflation adjustments in social security payments.

The wage gap between men and women showed no change. Women on average had an income of $39,200 last year compared with $50,000 for men — meaning they earned 78 percent of what men earned.

“That means that millions of women and their families continue to slide backwards year after year,” said Fatima Goss Graves, vice president for education and employment at the National Women’s Law Center. ” We can and must do better than this. It’s time to close the wage gap now.”

The annual report also included data on health insurance coverage. The Census Bureau found that 13.4 percent of Americans did not have coverage for the entire year.

The Census Bureau said it made changes in the way it calculated that figure as it prepared to gauge the effect of coverage that began this year under the Affordable Care Act, also known as Obamacare.

Under the previous methodology, the percentage of people without health insurance had dropped to 15.4 percent in 2012. But Census officials said the 2013 figure should not be compared to the 2012 one.

The nation’s high poverty rate has been a key argument for advocates of increasing the federal minimum wage from its current $7.25 an hour.

About 17 percent of restaurant workers live below the poverty line, according to a report last month by the Economic Policy Institute. Fast-food workers have held protests in Los Angeles and other cities urging a higher minimum wage.

The non-partisan Congressional Budget Office has said increasing the federal minimum wage to $10.10 an hour would lift 900,000 people above the poverty line.

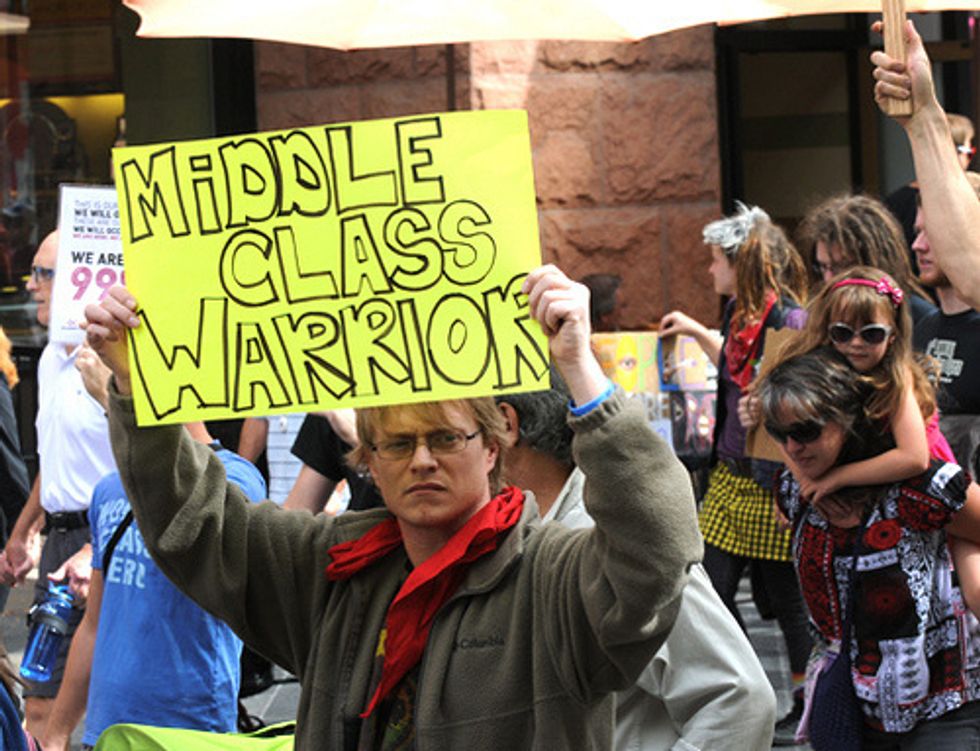

AFP Photo/Scott Olson

Interested in economic news? Sign up for our daily email newsletter!