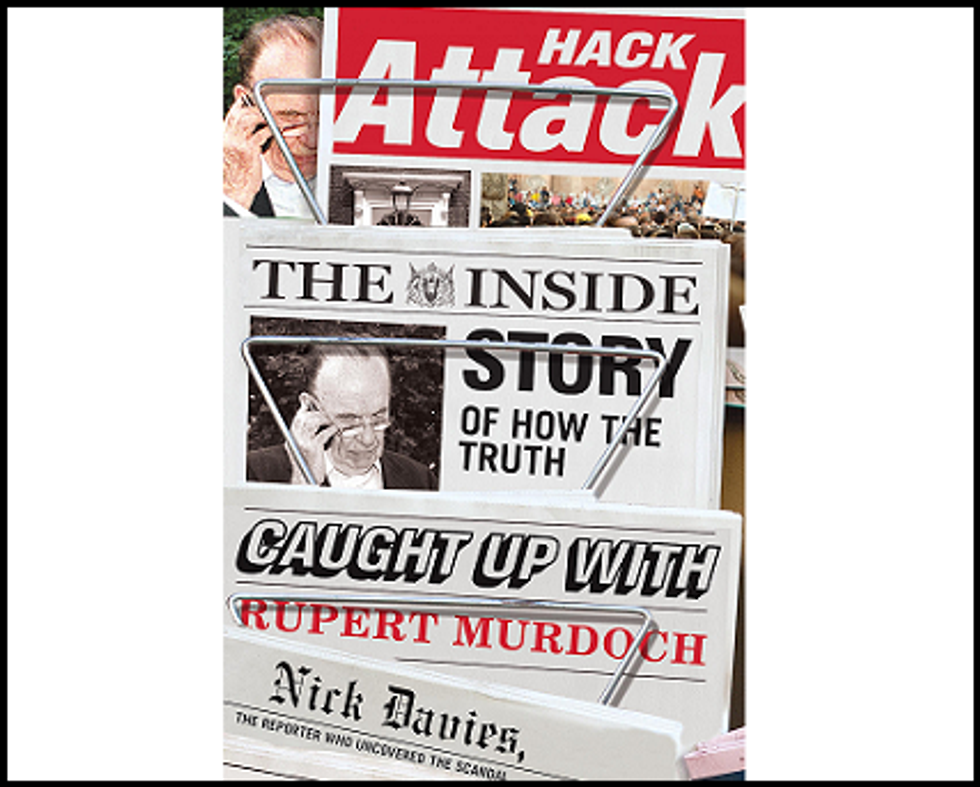

Weekend Reader: ‘Hack Attack: The Inside Story Of How The Truth Caught Up With Rupert Murdoch’

For over four decades, Rupert Murdoch presided over one of the largest and most powerful news conglomerates in history. But this magnate who inspired fear and loathing in politicians, journalists, and public figures, nearly saw it all come crashing down when The Guardian and Scotland Yard pursued an investigation into Murdoch’s papers’ regime of hacking, burglary, and wiretapping — an investigation that ended in a spate of arrests, dismissals, and the partial dismantling of an empire.

In Hack Attack, journalist Nick Davies recounts the investigation from its quiet beginnings as a minor news item to a criminal trial that rocked the media world.

In the following excerpt, Davies traces Murdoch’s ascendancy from enfant terrible to unassailable mogul.

You can purchase the book here.

When he first arrived in the United Kingdom in January 1969, to buy the News of the World, Rupert Murdoch had no significant political muscle.

In the eyes of the U.K. establishment he was a young (aged thirty-seven), slightly plump, socially ill-at-ease businessman who had one supremely attractive characteristic: he was not Robert Maxwell, the ego-driven and corrupt millionaire whose lust for power was as subtle as snakebite and who had been closing in fast on the News of the World. Murdoch slipped in, offered a bigger buck and was warmly welcomed as the new owner.

For a couple of years, the worst that was said of him was that he was, well, a touch vulgar. The News of the World had never been acceptable in polite society. It specialised in the bawdy, a bit like the best kind of working man’s pub – warm and cheerful, good for a laugh, with a flash of stocking top too. It picked up on obscure court cases, especially the ones where a doctor or a country parson was accused of fumbling with the undercarriage of some local widow. Murdoch soon started to push the boundaries.

Within months of taking over, he serialised the memoirs of Christine Keeler, the elegant young woman who had caused huge scandal by wrapping her long, slim legs around the then Secretary of State for war, the Conservative MP John Profumo, who had not only enjoyed an exciting affair with her but then lied to Parliament about it. This had all happened six years earlier: Profumo had resigned; the government had been disgraced. This was simply the inside story of what had gone on between the sheets. But it was good for sales.

A few years later, he did far more of the same when his journalists joined in exposing the Conservative peer Lord Lambton, who had found another elegant young call girl, Norma Levy, to play with, while a News of the World photographer peeked through a hole in the wall and captured the whole sweaty business on film. More sales, more money.

Even after he bought the Sun, later in 1969, he was still no kind of power-monger in the U.K. He rescued a newspaper that was tottering towards the grave and once again increased its sales, with brash headlines, sensational stories and all the nudes that were fit to print. The Times observed that ‘Mr. Murdoch has not invented sex but he does show a remarkable enthusiasm for its benefits to circulation.’

Still, the formula worked. By 1978, the Sun had become the most popular daily paper in the U.K., and Murdoch finally began to become a serious player. Noisily, his two papers backed Margaret Thatcher all the way to Downing Street in April 1979 – and the great game of power began.

In 1981, two years after Mrs. Thatcher became prime minister, Murdoch set out to buy The Times and the Sunday Times. The Thatcher government generously opened the way for him, choosing not to refer his bid to the regulator, the Monopolies and Mergers Commission, who would have had good grounds to block it. Government records that were finally released thirty-one years later, in 2012, disclosed that Murdoch secretly met Mrs. Thatcher for a Sunday lunch at Chequers just as the deal was being put together. Murdoch and the government pretended that the two newspapers were exempt from monopoly law because they were on the verge of financial collapse. It wasn’t true.

There was outrage in Parliament and bitter comment from rival newspapers, but Murdoch got what he wanted and, with that deal, established himself as the biggest newspaper proprietor in the U.K., a man whom politicians now certainly wished to please.

So it was that in 1986, when Murdoch wanted to stop Robert Maxwell buying the Today newspaper, the Thatcher government referred Maxwell’s bid to the Monopolies Commission, which blocked it; and in 1987, when he himself wanted to buy Today, the government reversed its position and chose not to involve the Monopolies Commission, so he bought it; and in 1990, when he was nurturing his new satellite TV company, Sky, while Mrs. Thatcher’s government was passing a communications bill with a new framework of regulation for television, Sky was exempted from almost all of it.

Later that same year, Mrs. Thatcher delivered one particularly graceful favour. Eighteen months after its launch, Sky TV was wallowing in failure, beaming four channels from the Astra satellite to the U.K. where just about nobody owned a dish to receive them, and losing some £2 million a week in the process. Murdoch wanted to save the company by merging with its only competitor, British Satellite Broadcasting, which was failing on an even grander scale but, as ever, this plan was clearly likely to run into trouble with the regulator, in this case the Independent Broadcasting Authority, which would object to the creation of a monopoly.

However, it so happened that the government was in the process of closing down the IBA and replacing it with a new regulator, to be known as the Independent Television Commission. There was a five-day gap between the death of the IBA and the birth of the IBA when there was simply no regulator in existence, and it so happened that during this brief moment of total non-regulation, the government looked away and quietly waved the merger through the legal fence: Murdoch was allowed to create BSkyB, with News Corp. effectively controlling its board, owning 50 percent of the company (later reduced to 39 percent by a share flotation).

As ever, this was not the result of a formal deal. There was a natural and easy relationship between Murdoch and Margaret Thatcher. They saw the world through the same hardline neoliberal eyes – unfettered capitalism, deregulated markets, privatised everything. His subsequent relationship with Tony Blair, from 1994, when he became Labour leader, was more awkward. Blair was arguably the most conservative leader in the history of the Labour Party, but nonetheless, he and his closest advisors embraced Rupert Murdoch the way a trainer embraces a tiger, with great care and genuine anxiety.

Some of Blair’s closest advisors privately looked on Murdoch and his crew with deep discomfort. Alastair Campbell once compared a lunch with senior Murdoch journalists to a meeting of the far-right British National Party. Certainly, they did not want to be pushed around by Murdoch; but Blair had seen how the Sun in 1992 had monstered the former Labour leader Neil Kinnock in order to help hand power to Murdoch’s chosen candidate, the Conservative John Major. He had seen, too, how Murdoch had then lost faith in Major, reaching the point where the Sun’s then editor, Kelvin MacKenzie, claimed to have answered an inquiry from Major about the following day’s coverage by telling him: “I’ve got a large bucket of shit on my desk and tomorrow morning, I’m going to pour it all over your head.” (In some versions of the story, Major replied weakly: “Oh, Kelvin, you are a wag.”)

With the simple aim of neutralising the threat, Blair and his advisors set out to finesse the relationship. Some of those involved say that their theory was that they would make no policy concession to Murdoch, but they would deliver three things: they would give his journalists stories; they would give him personal flattery and attention; and, every so often, when there was a policy which they themselves had chosen but which they knew would please him, they would wrap it up with a red ribbon and present it to him as though it were a gift. These same sources agree that it didn’t work.

From the outset, they compromised. When Blair returned to London from his first bonding with Murdoch at News Corp’s annual gathering, at Hayman Island, Australia, in 1995, one of his party’s first acts was to change their media policy in Murdoch’s favour – killing off their commitment for an urgent inquiry into foreign ownership of the news media, and withdrawing their plan to bring in a privacy law, to protect the victims of tabloid intrusion. It was not that Murdoch had threatened to monster them if they stuck to their policy, simply that they feared that he might and thought it prudent to send a signal which might placate him (although Blair continues to insist he had his own independent reasons for the change).

But this was a complicated relationship, and Blair’s people did try to stand up to Murdoch. He wanted to buy Manchester United, and they stopped him. He didn’t want them to create the new TV regulator, Ofcom, but they did. He didn’t want them to give the BBC new channels or to increase the licence fee, but they did both. However, the longer the game went on, the harder it was to keep the tiger in its place.

If you enjoyed this excerpt, you can purchase the full book here.

Excerpted fromHack Attack by Nick Davies. Published by FABER AND FABER, INC. an affiliate of FARRAR, STRAUS AND GIROUX, LLC. Copyright © 2014 by Nick Davies. All rights reserved.

Want more updates on great books? Sign up for our daily email newsletter here!