Nevada Democrats Announce Telephone Voting In 2020 Caucus

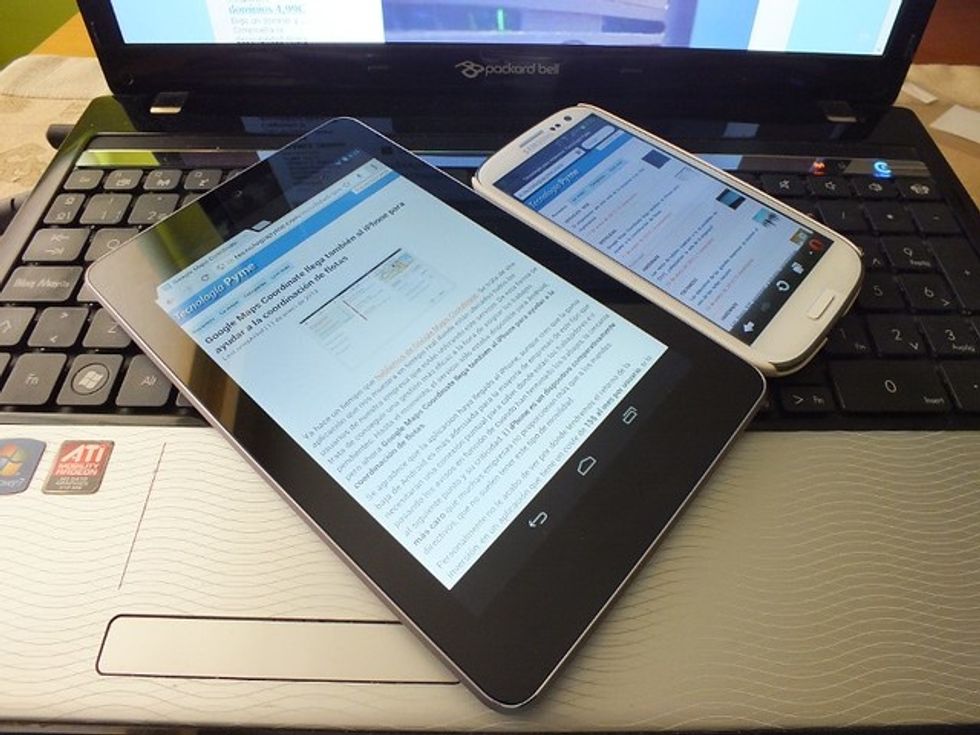

On July 8, the Nevada State Democratic Party announced that it would be holding the 2020 presidential election’s “first in the West Virtual Caucus,” where party members can vote early by landline phones and smartphones in the third nominating contest.

“Earlier this year, the Nevada State Democratic Party released a delegate selection plan that laid out our blueprint to make 2020 our most accessible, expansive and transparent caucus yet,” Nevada State Democratic Party Chair William McCurdy II said. “Today, with the announcement of our virtual caucus process, we are one step closer to making our blueprint a reality.”

“Nevada Democrats will have three options on making their voice heard next February,” he continued. “They’ll be able to vote in person at any [predetermined] location in their county on any of the four early voting days between Feb. 15 and 18, vote from home or on the go using their phone by way of our virtual caucus, or attend, in person, on caucus day [Feb. 22], at their assigned precinct.”

Nevada officials, like those in Iowa, whose caucuses launch the 2020 season and will also offer a “virtual caucusing” option, hope that their early and off-site voting will increase participation. But Nevada’s upbeat announcement revealed little of the complexities and unresolved aspects of their proposed overall phone and online system. A key national party committee has not approved its plans, but has raised serious concerns that remain to be addressed.

“Technology, ranked-choice voting, recounts—those are the issues we really have to drill down on, because we are kind of skimming the surface,” said Lorraine Miller, co-chair of the Rules and Bylaws Committee (RBC) of the Democratic National Committee from Texas, after the panel spent more than an hour questioning Nevada’s plans on June 28 and then granted “conditional” approval.

“Our technology questions are not just security questions. That’s [only] one way to look at technology,” said James Roosevelt III, an RBC co-chair from Massachusetts, echoing Miller and saying the DNC staff would have to more deeply assess Nevada’s proposal before the RBC meets next in late July, when it may vote to approve its plans.

But you would never know of these concerns from listening to the Nevada party (NSDP) officials at their July 8 press conference, nor from reading their press materials, which included a quote from DNC Chair Tom Perez praising the state “for stepping up and taking action to expand access.” Indeed, key parts of Nevada’s envisioned 2020 virtual voting system only exist on paper and have not yet been evaluated for security or usability, but have led to tangible consternation for the DNC Rules Committee.

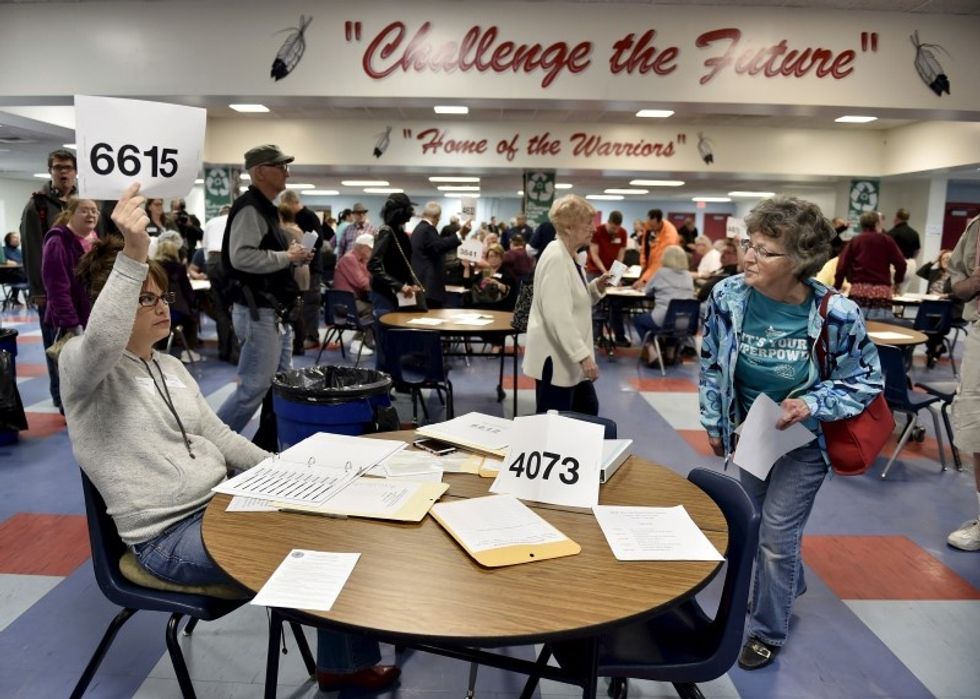

“It seems to me a pretty gargantuan task,” said Harold Ickes, one of the national party’s top procedural experts and an RBC member from Washington, D.C., after a long exchange over a to-be-created app to be used by volunteer caucus chairs in 1,700-plus precincts. The app will report the early and virtual vote results for that precinct, which will be transmitted from vendors at party headquarters. The chair then will have to enter the room’s in-person voting results in each successive round of voting—all while maintaining order as candidates are eliminated during the presidential caucus.

Following DNC Instructions

Only a few state Democratic parties will hold caucuses in 2020 to choose a nominee. The first contest, in Iowa, and third, in Nevada, are in this group. The state party—not local election officials—will oversee the process. In short, the party will rent the voting system from a mix of private vendors to reach the participation goals in national party directives. These requirements include 2020 rules that allow “the casting of ballots over the Internet” in caucuses for those unable to physically attend, and “a paper record” trail of the votes cast, should a presidential candidate demand a recount.

The Nevada party, like its counterpart in Iowa, has embraced this call for modernizing their caucuses. In recent months, the NSDP has hired staff and aggressively worked with vendors to develop their plans. This overall system includes a registration component; voter contact and vetting when they log in; ballot interfaces for voters using landline telephones or smartphones to make their choices; the recording, transmitting, tabulating and encrypting of the presidential votes—where candidates are ranked but votes for disqualified candidates won’t count; and where remote votes are blended in with the rounds of live voting at about 1,700 local caucuses. And there’s to be a paper record of votes in case of a recount.

It is not an understatement to suggest that the NSDP, responding to the DNC’s 2020 Delegate Selection Rules, is trying to stand up one of the most sophisticated new voting systems in America—and do it in record time. It is also true that as the complexity of this task has crystallized before the DNC’s Rules and Bylaws Committee, which wrote 2020’s rules—which are goals and procedures, not technicalities for making it work—that a tension has emerged.

The Rules Committee’s most vocal members seem to realize that their caucus states may be taking on too much—even if they are following their 2020 rules. These members are well aware that in today’s political world, any hiccup or error, no matter the cause, will be used to undermine an election’s credibility. Meanwhile, state parties in Iowa, and especially Nevada, are digging in and saying that they and their vendors will successfully modernize and deploy the most modern phone- and internet-based systems.

The friction could be seen in Pittsburgh in late June, when the RBC reviewed the 2020 delegate selection plans from 22 states, but spent most of the time on Iowa and Nevada. Both states’ party officials answered questions about goals and details and won “conditional” approval. But the DNC’s voting procedure experts did not enthusiastically support Nevada’s plan to deploy telephone voting and an online vote-counting infrastructure. Many complex issues had to be resolved before granting formal approval, the co-chairs said. Nonetheless, Nevada’s party held a telephone press conference on July 8, “to announce the first in the West virtual caucus,” enthusiastically promoting their 2020 plans.

“The NV Dems’ virtual caucus allows participants to confirm [their candidate] selections every step of the way,” said Caucus

“There’s a big delta [gap] between this group’s technical expertise as it is related to delegate counting and our technical expertise as it relates to technology,” Yohannes Abraham, an RBC member from Virginia, said before the panel “conditionally” endorsed Nevada’s plan. “If it is in our purview to sign off on both the technology and the actual delegate selection, and obviously those things cannot be disaggregated, I don’t think we can do that in good conscience prior to the July meeting without a real in-depth briefing.”

Back in their vote-counting wheelhouse, the RBC’s most vocal members asked how volunteers who serve as the caucus chairs and their assistants in the 1,700-plus precinct caucuses would manage possibly unruly rooms after announcing results from the early and virtual voting—voters not physically present—and then do the vote-count math as the candidate elimination rounds continue.

The virtual results, from four days of early voting and two other days of early phone voting, would be sent by the party vendors and appear on the app given to each precinct chair. These votes, could, conceivably, alter the outcome in the room, where contenders with less than 15 percent of the vote are eliminated from future rounds. The chairs were also to use a calculator on the app to record and determine the results during every ensuing round, where only the still-viable candidate votes (from early and virtual ballots) had to be processed along with the votes inside the caucus rooms.

“That’s a lot of information for the precinct chairman,” said Ickes, one of the DNC’s top procedural experts and an RBC member from Washington, D.C., launching a detailed discussion.

Shelby Wiltz on the press call. “It allows all voters the ability to participate using a landline, a cell phone, or the ability to dial in using Skype or Google Hangouts.”

Nevada and the Rules Committee

At late June’s Rules and Bylaws Committee meeting, some of the most seasoned and vocal members were skeptical about Nevada’s proposed virtual system and vote-counting procedures. Some said that they could not evaluate cyber-security issues, saying the DNC technology and security staff would have to assist them, and called for “a real in-depth” briefing before revisiting Nevada’s proposal.

“There’s a big delta [gap] between this group’s technical expertise as it is related to delegate counting and our technical expertise as it relates to technology,” Yohannes Abraham, an RBC member from Virginia, said before the panel “conditionally” endorsed Nevada’s plan. “If it is in our purview to sign off on both the technology and the actual delegate selection, and obviously those things cannot be disaggregated, I don’t think we can do that in good conscience prior to the July meeting without a real in-depth briefing.”

Back in their vote-counting wheelhouse, the RBC’s most vocal members asked how volunteers who serve as the caucus chairs and their assistants in the 1,700-plus precinct caucuses would manage possibly unruly rooms after announcing results from the early and virtual voting—voters not physically present—and then do the vote-count math as the candidate elimination rounds continue.

The virtual results, from four days of early voting and two other days of early phone voting, would be sent by the party vendors and appear on the app given to each precinct chair. These votes, could, conceivably, alter the outcome in the room, where contenders with less than 15 percent of the vote are eliminated from future rounds. The chairs were also to use a calculator on the app to record and determine the results during every ensuing round, where only the still-viable candidate votes (from early and virtual ballots) had to be processed along with the votes inside the caucus rooms.

“That’s a lot of information for the precinct chairman,” said Ickes, one of the DNC’s top procedural experts and an RBC member from Washington, D.C., launching a detailed discussion.

“It is,” replied Wiltz. “But we really look forward to the process.”

“But you haven’t developed that system of integrating all this information so the precinct chair can handle it efficiently and clearly, yet?” Ickes said, referring to what Wiltz later described as “a secure calculation tool, a caucus app and calculator to allow precinct captains to do the math at their precincts on caucus day.”

“No, not yet,” Wiltz replied, “but we’ve been spending the last two months working closely to review proposals from vendors that are going to assist us with that task.”

The exchange was met by silence. Minutes before, questioning by Ickes revealed that the state party had not yet developed the voter registration and vetting system that it said would be used so that a voter could not vote twice—but also could participate in precinct caucuses if they signed up to vote virtually but did not vote that way. Wiltz said that system “does not yet exist,” but would be “similar to caucus tracking systems” the party used in 2016.

These disclosures raised concerns, which, in some cases, could not be addressed because there was not enough available information. Specifically, it’s hard to evaluate an app or other parts of a wider voting system, when those elements exist on paper or were last used by another client but are awaiting customization for 2020.

Jeff Berman, an RBC member from Washington, D.C., followed the exchange between Ickes and Wiltz by asking how local precincts would be staffed “to handle this more complicated calculation,” referring to the vote-counting elements and stages.

Wiltz replied that “precinct captains and site leads” would receive extensive training, and the highest-profile caucus sites would have NSDP staff present. The party would also set up a hotline “to assist with any issues” and “deploy additional volunteers as necessary to help put out any fires,” she said.

Berman replied, “I’ll just say in 2016 I observed a caucus in Iowa and it was, for some reason, a location where nobody was the chair of—so basically there were about 100 people in the room and [they were] equally divided between the two main candidates, trying to figure out what to do. And that was without electronic information coming in that somebody was supposed to master.”

At that point, Artie Blanco, Nevada’s Rules Committee member, stepped in to stop the escalating doubts and express her confidence that the state party and its caucus plan would succeed—increasing participation and capably managing the process.

“We have been working on what this system will look like,” said Blanco. “Like Shelby has mentioned, we have been working lockstep with the DNC technology department; to ensure that the vendors that we are reviewing—that we are seriously in consideration with—and have already discussed the potential technology that will be used on that day. I know you have questions, but it will result—we feel very confident that it will result in a system that will work for our volunteer precinct chairs.”

“I don’t doubt your commitment, and the commitment of your colleagues, but I wonder how the person who is the precinct chair, or managing [the caucus], handles the figuring out of the threshold,” replied Ickes, referring to the count math that disqualifies candidates.

“Because that [voting] is going to be coming in from three different sources: One, the people who walk in; two, the people who vote early; three, the people who voted virtually. And the latter two, as I understand it, are going in ranked order,” he said. “So here you’ve got a precinct chairman, managing the people in there, and sometimes it can get quite boisterous, and then having to figure out the threshold by integrating all of this information. In theory, can it be done? The answer is yes. …[A]nd the system, according to you, has not even been designed yet. It seems to me a pretty gargantuan task to do.”

Wiltz replied that she understood Ickes’ concerns, but said Nevada was responding to “the requirements that the DNC has given to all states, and requirements that we are excited about taking on.”

She continued, “One of those requirements is to provide people with an option to participate virtually or absentee. One of those requirements is to allow an early vote process. In order to do that, we have to make a decision about how… we count the votes of people who participate in those processes. This is something that any [caucus] state like us would grapple with. We have the option to give those folks their own precinct. We also have the option to have those votes counted in-person at their precinct. We have obviously chosen the latter.”

As the discussion continued, other RBC members had questions about slight variations in the candidate ranking process to be used by the early and virtual voters, compared to those in caucus rooms. Wiltz told everyone not to worry, as a vendor would do all the vote-counting math, including on the app given to the caucus chairs.

“Harold, the math is not going to be dependent on the precinct chair,” she said, addressing Ickes. “That is, the technology that is being built, the math will be set in a system that will be part of our [overall] technology. So that’s the point to your question.”

Other Issues and Questions

As the review continued, RBC members raised still other concerns. One question was whether Nevada’s plan to add early and virtual votes into the results in about 1,700 local precincts was preferable to the approach taken by Iowa. It was creating four new precincts across the entire state, where early and remote votes would be counted separately and added into statewide caucus totals. During Iowa’s presentation, its officials said they made that choice to simplify the process, even though it was a departure from caucus tradition.

It also emerged that NSDP officials had not yet decided how many candidates these voters were to rank. In Iowa, the virtual voters are to rank five top choices. Iowa officials said that ranking five of the choices was likely to include at least one viable candidate from that voter’s precinct caucus—if they chose to attend that event.

The volume of candidates to be ranked would affect the process’s complexity—starting with the time required by older voters using phone keypads to repeatedly enter their choices after hearing a list of the candidates read out (after logging into the phone system). There are currently two-dozen presidential candidates.

“We are working with our vendors to understand what the threshold is for the number of choices or preferences that we need to provide someone who votes early or virtually,” Wiltz said. “We have not yet set that number.”

There were still other questions. Longtime RBC member Donna Brazile of Washington, D.C., who stepped in as DNC chairwoman in 2016 and managed Al Gore’s presidential campaign, asked why the registration deadline for early voting was November 30, 2019, when the state government’s registration deadline was in early February—and the NSDP would allow same-day registration for early voters and in-person caucus participants. Wiltz replied that the early deadline was needed to create voter rolls ensuring that nobody could vote in more than one setting.

“The security issue I am worried about comes up not when somebody tries to vote twice,” said David McDonald, an RBC member from Washington. “It’s when the opposition campaign shows up and tries to vote in your name, and then you go to your caucus and you’ve been disqualified by a security procedure.”

McDonald also asked about potential “Wi-Fi issues” in precincts that could interfere with the use of an app by the chair. During Iowa’s presentation, he asked how the electronic voting would produce a paper trail of all of the votes, but that issue did not surface in discussing Nevada’s proposal.

Both Iowa and Nevada said they would be introducing presidential preference cards in their precinct caucuses, where voters would list their first and final choices, as a way of documenting the votes. During Iowa’s review, McDonald expressed concerns about the collection and custody of those cards, which would have to be turned in from roughly 1,700 caucus sites in each state.

Iowa and Nevada party officials also said that they were talking to vendors about emailing a ballot summary receipt to virtual voters, which Wiltz called a “voter verified paper record” in her opening remarks summarizing their proposed system. RBC members did not ask about that receipt.

Members of the DNC’s technology and security staff sat behind the RBC members and took notes, but wouldn’t comment to the press about how they conducted their reviews that lead to making recommendations that all of the state’s 2020 plans before the panel be conditionally approved—including Nevada’s plan, which has central elements that do not yet exist.

Pressing Ahead

As the Nevada review continued, state party officials stressed they were planning to undertake unprecedented levels of training for the caucus volunteers and the party’s partners—such as the 58,000-member Culinary Workers Union Local 226. In addition to online training, and new training materials in several Asian languages, Wiltz said there would be “150 training sessions between now and February 22.”

“Everything we are doing in 2020 is more aggressive,” she said. “And it’s bigger. And it also ensures that we are meeting the requirements of the DNC and that we are committing ourselves to the values that we have as a party—which is to expand the process for people that otherwise would not be able to participate.”

After an hour, Artie Blanco, the lone RBC member from Nevada, made the formal motion to conditionally approve the state’s 2020 plan. The RBC gave its assent, but not before members voiced concern, including Co-Chair James Roosevelt III, who looked to the panel’s next meeting and said, “We’ve got a lot of stuff, for lack of a better word, that we probably should get ironed out.”

“It just strikes me that we are not going to find resolution on a lot of these things without a more detailed briefing from our technology staff at the DNC,” Virginia’s Abraham added.

“We are thinking along the same lines,” replied Co-Chair Lorraine Miller, after comparing her notes with Roosevelt.

The Rules and Bylaws Committee will next meet in late July and will consider more details from the Nevada State Democratic Party and the DNC technology and security staff. If satisfied, it may then formally approve both Nevada’s and Iowa’s virtual voting plans.

But in the meantime, Nevada party officials have begun telling the press and public to expect they can vote to nominate a presidential candidate using their landline phone or smartphone.

“Our virtual caucus will offer Nevada Democrats the opportunity to participate in the caucus from home, whether it be those overseas serving in our military, those homebound due to a disability or illness, or any Democrat unable to attend on caucus day,” said NSDP Chair William McCurdy II on July 8, at the beginning of the press conference announcing virtual voting.

This article was produced by Voting Booth, a project of the Independent Media Institute.