Oct. 17 (Bloomberg) — Killing terrorists with drones is great politics. To the question, “Is it legal?” a natural answer might well be, “Who cares?”

But the legal justifications in the war on terrorism do matter — and not just to people who care about civil liberties. They end up structuring policy. As it turns out, targeted killing, now the hallmark of the Barack Obama administration’s war on terrorism, has its roots in rejection of the legal justifications once offered for waterboarding prisoners.

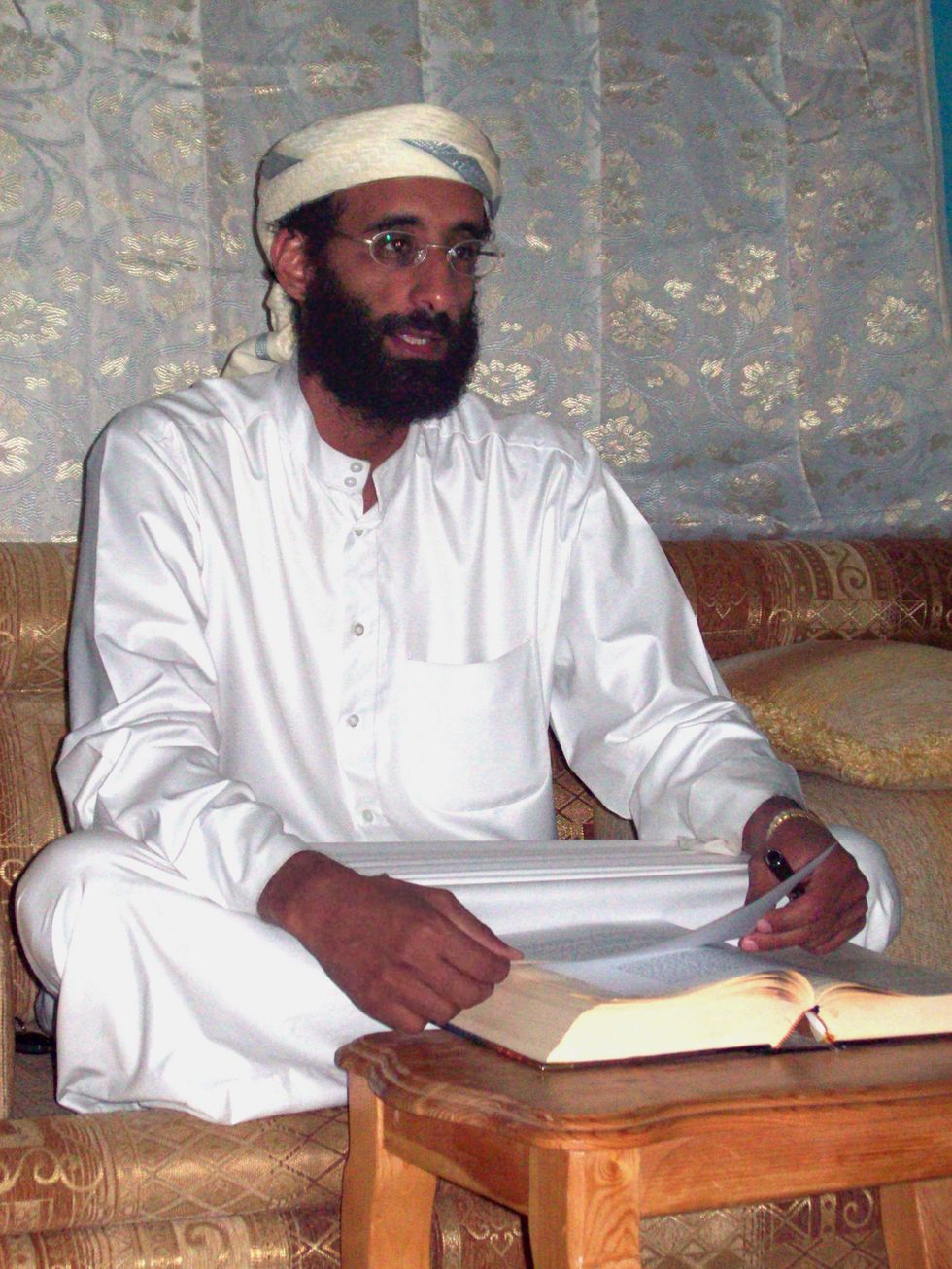

The leaking of the basic content (but not the text) of an Obama administration memo authorizing the drone strike that killed U.S. citizen Anwar Al-Awlaki therefore calls for serious reflection about where the war on terrorists has been — and where it is headed next.

The George W. Bush administration’s signature anti-terror policy after the Sept. 11 attacks (apart from invading countries) was to capture suspected terrorists, detain them, and question them aggressively in the hopes of gaining actionable intelligence to prevent more attacks.

In the Bush years, after the CIA and other agencies balked at the interrogation techniques being urged by Vice President Dick Cheney, the White House asked the Department of Justice to explain why the most aggressive questioning tactics were legal. Lawyers at the Office of Legal Counsel — especially John Yoo, now a professor at the University of California at Berkeley — produced secret memos arguing that waterboarding wasn’t torture.

The Torture Memos

What was more, the memos maintained, it didn’t matter if it was torture or not, because the president had the inherent constitutional authority to do whatever was needed to protect the country.

Some of the documents were leaked and quickly dubbed “the torture memos.” A firestorm of legal criticism followed. One of the most astute and outraged critics was Marty Lederman, who had served in the Office of Legal Counsel under President Bill Clinton. With David Barron, a colleague of mine at Harvard, Lederman went on to write two academic articles attacking the Bush administration’s theories of expansive presidential power. Eventually, Jack Goldsmith, who led the Office of Legal Council in 2003-04 (and is now also at Harvard), retracted the most extreme of Yoo’s arguments about the president’s inherent power.

In the years leading to the 2008 election, all this technical criticism of the Bush team’s legal strategy merged with domestic and global condemnation of the administration’s detention policies. The Supreme Court weighed in, finding that detainees were entitled to hearings and better tribunals than were being offered. As a candidate, Obama joined the bandwagon, promising to close the prison at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, within a year of taking office.

Guantanamo is still open, in part because Congress put obstacles in the way. Instead of detaining new terror suspects there, however, Obama vastly expanded the tactic of targeting them, with eight times more drone strikes in his first year than in all of Bush’s time in office. Barron and Lederman, the erstwhile Bush critics, were appointed to senior positions in the Office of Legal Counsel — where they wrote the recent memo authorizing the Al-Awlaki killing.

What explains these startling developments? If it’s illegal and wrong to capture suspected terrorists and detain them indefinitely without a hearing, how exactly did the Obama administration decide it was desirable and lawful to target and kill them?

The politics were straightforward. Obama’s team observed that holding terror suspects exposed the Bush administration to harsh criticism (including their own). They wanted to avoid adding detainees at Guantanamo or elsewhere.

A Father’s Appeal

Dead terrorists tell no tales — and they also have no lawyers shouting about their human rights. Before Al-Awlaki was killed, his father sued the government for putting the son on its target list. The Obama Justice Department asked the court to dismiss the claim as being too closely related to government secrets. The court agreed — a result never reached in all the Guantanamo litigation. Anwar Al-Awlaki now has no posthumous recourse.

In the bigger picture, Obama also wanted to show measurable success in the war on terrorism while withdrawing troops from Iraq and Afghanistan. But even here the means were influenced by legal concerns.

Osama bin Laden is the best example. One suspects that the U.S. forces who led the fatal raid in Abbottabad almost certainly could have taken him alive. But detaining and trying him would probably have been a political disaster. So they shot him on sight, as the international law of war allows for enemies unless they surrender.

The authority for targeted killing — as expressed in the Lederman-Barron memo — offers the legal counterpart to the political advantages of the Obama targeting policy. According to the leaks, the memo holds that the U.S. can kill suspected terrorists from the air not because the president has inherent power, but because Congress declared war on Al-Qaeda the week after the Sept. 11 attacks.

The logic is that once Congress declares war, the president can determine whom we are fighting. The president found that Yemen-based Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, which didn’t exist on Sept. 11, had joined the war in progress. He determined that Al-Awlaki was an active member of the Yemeni groups with some role in planning attacks. And, the memo says, it’s not unlawful assassination or murder if the targets are wartime enemies.

From a formal legal standpoint, Lederman and Barron can claim consistency with their attacks on the Bush administration. They relied on Congress and international law; Yoo’s “torture memos” didn’t.

But this argument misses the more basic point: Most critics rejected Bush’s policies not on technical grounds based on the Constitution, but because they thought there was something wrong with the president acting as judge and jury in the war on terrorism.

No Defense Allowed

Anwar al-Awlaki was killed because the president decided he was an enemy. Like the Bush-era Guantanamo detainees, he had no chance to deny this — even when his father tried to go to court while he was still alive.

Naturally, a uniformed soldier in a regular war also wouldn’t get a hearing. But like the Guantanamo detainees, Al- Awlaki wore no uniform. Nor was he on a battlefield, except according to the view that anywhere in the world can be the battlefield in the war on terrorism.

Al-Awlaki might have maintained that he was merely a jihadi propagandist exercising his free speech rights as a U.S. citizen. Which might well have been a lie. Yet we have only the president’s word that he was an active terrorist — and that is all we will ever have. The future direction of the policy is therefore clear: Killing is safer, easier and legally superior to catching and detaining.

Sitting beside Al-Awlaki when he was killed was another U.S. citizen, Samir Khan, who was apparently a full-time propagandist, not an operational terrorist. Khan was, we are told, not the target, but collateral damage — a good kill under the laws of war.

Legal memos are weapons of combat — no matter who is writing them.

(Noah Feldman, a law professor at Harvard University and the author of “Scorpions: The Battles and Triumphs of FDR’s Great Supreme Court Justices,” is a Bloomberg View columnist. The opinions expressed are his own.)