For Democratic Society, Some Monumentally Hard Decisions Ahead

One of the recently vandalized monuments is a statue of poet John Greenleaf Whittier. Someone smeared "BLM" and "(expletive) Slave Owners" on the seated figure prominently displayed in the city named after him, Whittier, California.

It happens that Whittier was a fiery abolitionist from Massachusetts. In a famous 1833 pamphlet, he called slavery "the master-evil before which all others dwindle into insignificance."

And so, who was behind his defacing? It could have been someone from the Black Lives Matter movement ignorant of Whittier's history. It could have been a goon just out to damage public property. It could have been a right-wing agitator trying to make the BLM movement look ridiculous.

No one knows. But there's developed a mindless war against public monuments, and it needs taming. Removing Confederate generals who made war on the United States to preserve slavery may be an easy call, but the future of all public monuments should be determined by public deliberation — not the self-anointed social warrior with a strong rope and 10 friends on Instagram.

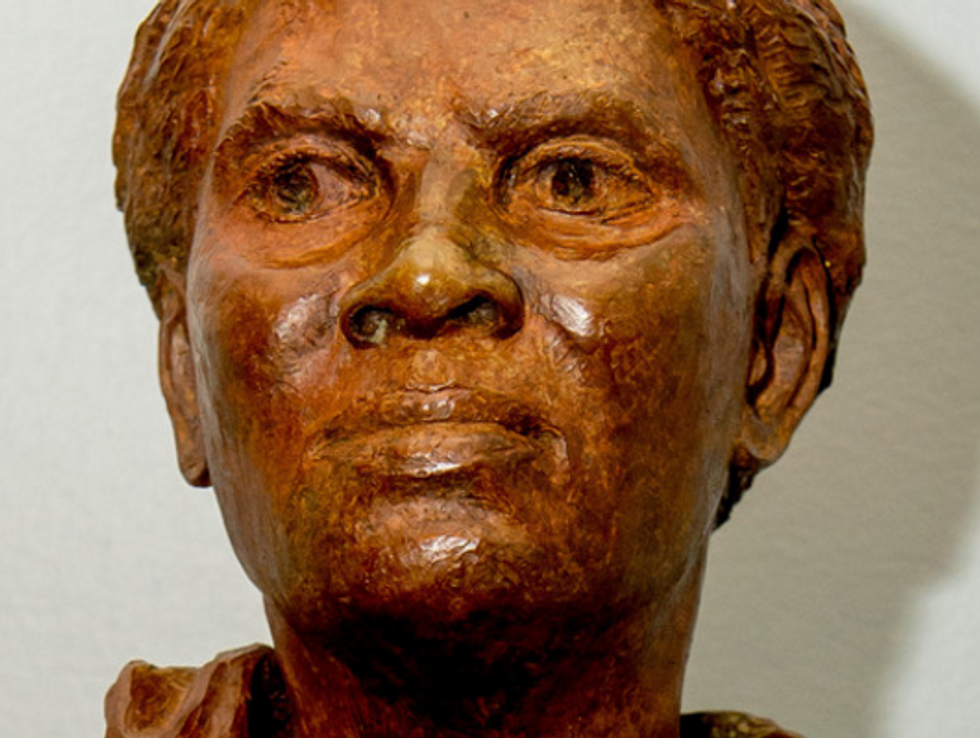

Consider the threats against the controversial statue of Abraham Lincoln and a freed slave at the Freedmen's Memorial in Washington. Historian David Blight agrees that the image comes off as racist and not something we would commission today. The 1876 monument shows Lincoln standing high over an African American on one knee.

But then Blight asks its critics to "please consider the people who created it and what it meant for their lives in a century not our own."

African Americans, most of them former slaves, had raised the $20,000 needed to build the monument. Nearly every black organization participated in its unveiling. Is it OK for woke moderns to cancel these African Americans' sense of their history? I don't think so.

Much is subject to interpretation. Some see the former slave crouching subserviently before Lincoln. Others see him rising up. Some object to his chains. Others see chains that are breaking, which, of course, is what was happening.

Most strange are complaints that the African American is naked from the waist up. That reflected the misery of bondage. Putting a nice shirt on him would have amounted to slavery denial — support for the claim by many slave owners that their captive, unpaid labor was well treated. (Slaves in ancient Rome were depicted without shirts, a sign of their degradation.)

That the sculptor, Thomas Ball, was white should be of no consequence. The emancipated blacks sponsoring the monument hired him, and that was their right. For the record, Ball said he considered Archer Alexander, the former slave who modeled as the freed man, an "agent in his own resistance."

What, if anything, should be done about the Freedmen's Memorial, which sits on federal land? Eleanor Holmes Norton, who represents the District of Columbia in Congress, plans to introduce legislation to have it removed.

But one hopes she will reconsider, that she will look again with more sensitivity toward those oppressed former slaves who had it built. And she might consider Blight's proposal to add rather than subtract from what's there.

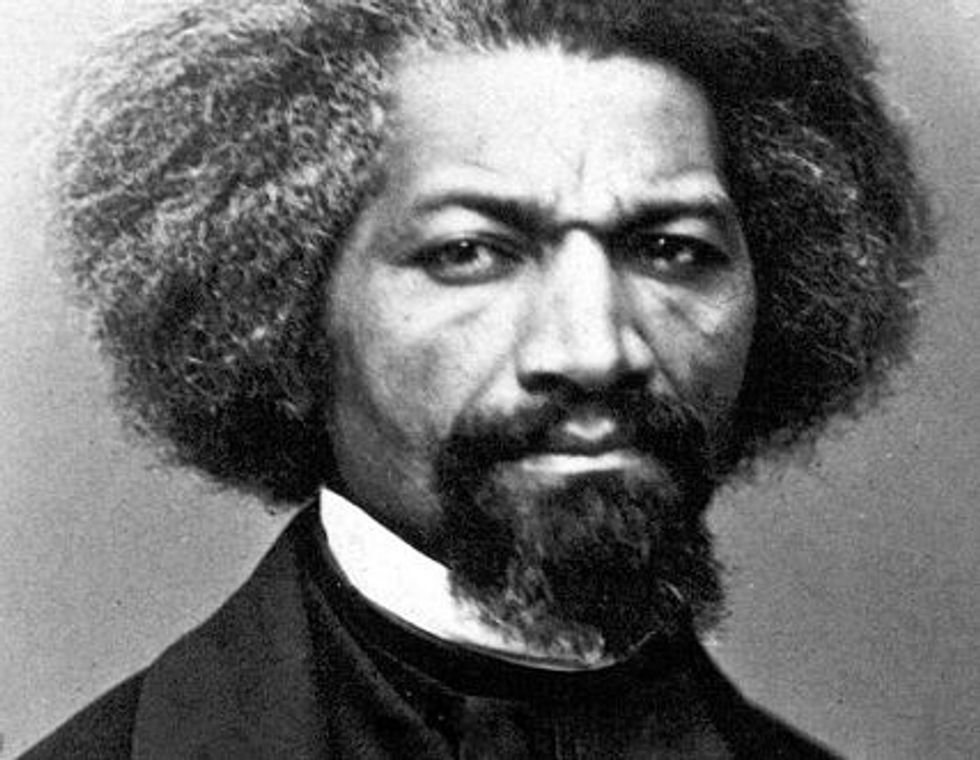

Black abolitionist Frederick Douglass spoke during the memorial's dedication ceremony. Blight, his biographer, suggests commissioning a statue of him giving his famous speech. It was a tough speech criticizing Lincoln for his early hesitation on the slavery question. Though Lincoln "tarried long in the mountain," Douglass concluded, he eventually arrived.

This reconsideration of the historic figures standing frozen in our downtowns has produced at least one positive outcome. Those willing to engage their brains are learning a lot of complicated history. There are some monumentally hard decisions to make, and only the broader public should make them.

Follow Froma Harrop on Twitter @FromaHarrop. She can be reached at fharrop@gmail.com. To find out more about Froma Harrop and read features by other Creators writers and cartoonists, visit the Creators webpage at www.creators.com.rom