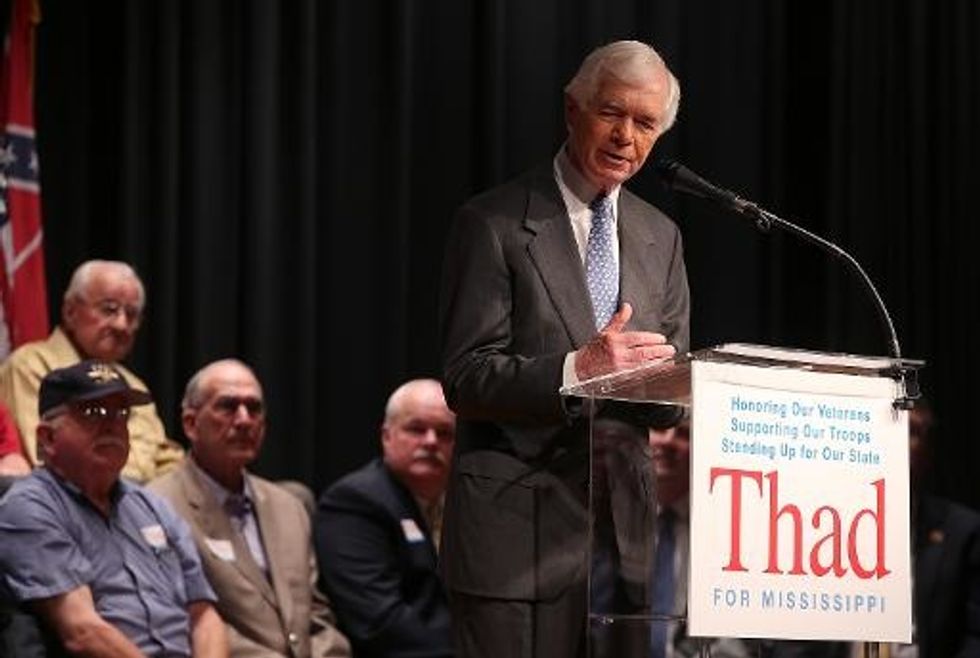

Mississippi NAACP Asks Cochran To Support Voting Rights Act After Black Voters Helped Him Win Runoff

Black voters helped propel Senator Thad Cochran (R-MS) to his victory against Tea Party challenger Chris McDaniel in the Mississippi Republican Senate runoff election on Tuesday night. Now the Mississippi NAACP is asking Cochran to start representing these voters’ interests — by supporting efforts to re-establish the Voting Rights Act protections that were struck down by the Supreme Court last year.

In a Wednesday interview with HuffPost Live, Mississippi NAACP president Derrick Johnson said, “Our advocacy towards [Cochran’s] office is to support amending the Voting Rights Act, free of any conditions such as voter ID. I think that this is an opportunity for him to show some reciprocity for African-Americans providing a strong level of support for him.”

Last June, the Supreme Court threw out Section 4 of the Voting Rights Act, which meant that states with a history of voting discrimination — like Mississippi — no longer need clearance from the federal government to make changes in their voting processes. The Court argued that the law was based on old data and that voting rights protections were no longer necessary.

Since then, many states have moved forward with strict voting restrictions, such as implementing voter ID laws and reducing early voting. According to the Brennan Center, 22 states have passed new restrictions since 2010; 15 states, including Mississippi, put new voting restrictions in place for the first time this year.

Many black voters who supported Cochran in the runoff didn’t turn out in the original primary, which McDaniel narrowly won. Mississippi’s primaries are open, which means that Democrats could vote in the runoff if they hadn’t voted in the original Democratic primary. In Jefferson County, which has the largest percentage of black voters in the country, turnout increased by 92 percent from the primary.

FiveThirtyEight‘s Harry Enten shows that Cochran could not have won without this increase in black voter turnout, as the 10 counties where Cochran did markedly better in the runoff than he did in the primary were counties where blacks make up 69 percent or more of the population.

This was no accident; Cochran’s campaign made a conscious effort to expand the electorate by getting black voters to the polls..

“We’ve got efforts reaching out to black voters in Mississippi who want to vote for Thad because they like what Thad is for,” Cochran campaign advisor Austin Barbour toldThe New York Times. “Thad Cochran is someone who, even with his conservative message, represents all of Mississippi.”

Now that Cochran’s on the other side of the hardest election of his career, Johnson feels that Cochran owes black voters, not just for his runoff win, but for the fact that he even became a senator at all.

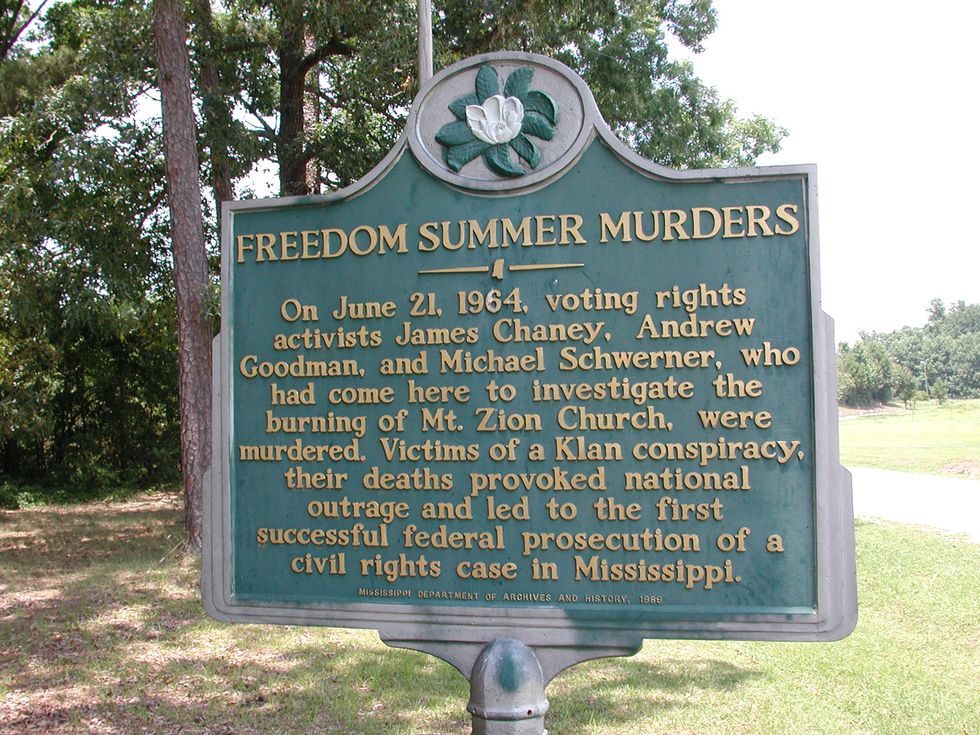

“Truth be told, not only would he not have won the election last night, he would not have been a sitting senator at all but for the volunteers and the staff of the NAACP, Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, CORE, who worked diligently over several years which culminated to what we now know as Freedom Summer,” he said in his HuffPost Live interview.

It’s been 50 years since Freedom Summer, when activists in Mississippi registered blacks to vote and set up schools in the face of resistance from the Ku Klux Klan and local residents.

Regardless of the history in his state, Cochran still supported the Supreme Court’s decision last year.

“The Court’s finding reflects well on the progress states like Mississippi have made over the last five decades,” he said in a statement after Section 4 was gutted. “I think our state can move forward and continue to ensure that our democratic processes are open and fair for all without being subject to excessive scrutiny by the Justice Department.”

Cochran’s office has shown no indication that the senator has changed his mind; on the contrary, it sees the runoff as evidence that Mississippi’s new voting rules work.

“Ballot access in Mississippi, with its new voter ID process, proved to be solid across the state on Tuesday,” Chris Gallegos, Cochran’s communications director, wrote in an email to The National Memo.

AFP Photo/Justin Sullivan

Interested in U.S. politics? Sign up for our daily email newsletter!