Supreme Court Rejects Florida’s Death-Penalty IQ Cutoff

By Michael Doyle, McClatchy Washington Bureau

WASHINGTON — A closely divided Supreme Court on Tuesday struck down Florida’s strict IQ cutoff for determining a convicted criminal’s eligibility for the death penalty.

In a 5-4 ruling that affects other states as well, the court concluded that Florida’s rigid IQ threshold of 70 “disregards established medical practice” and creates the “unacceptable risk” that an inmate with intellectual disabilities might be executed, in violation of the Constitution.

“Our society does not consider this strict cutoff as proper or humane,” Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote.

Instead, Kennedy and the court’s four liberal justices concluded, Florida must consider IQ testing’s standard error of measurement, as well as other factors, in evaluating intellectual disability. This is already the practice in most of the nation’s other death-penalty states.

“By failing to take into account the (standard error of measurement) and setting a strict cutoff at 70, Florida goes against the unanimous professional consensus,” Kennedy wrote. “The flaws in Florida’s law are the result of the inherent error in IQ tests themselves.”

Conservative Justice Samuel Alito, writing for the dissenters, noted that nine other states besides Florida effectively impose strict IQ cutoffs of 70 when determining eligibility for the death penalty. These other states also might face new pressure to change their practices.

“It is quite wrong for the court to proclaim that ‘the vast majority of states’ have rejected Florida’s approach,” Alito wrote. “The states have adopted a multitude of approaches to a very difficult question.”

The state tally is important to justices on all sides, because it can measure what the Supreme Court calls the “evolving standards of decency” concerning criminal penalties and punishments. Citing these evolving standards, for instance, the high court in 2005 banned the death penalty for those who commit crimes under the age of 18.

Kennedy wrote the 2005 opinion, as well.

Freddie Lee Hall, the 68-year-old convicted murderer who’s at the heart of the case decided Tuesday, has been on the state’s death row since 1978. He and an accomplice were convicted of murdering a 21-year-old pregnant woman and a Hernando County deputy sheriff.

The 16th of 17 children, Hall was “tortured by his mother and abused by his neighbors,” according to a 1993 dissenting opinion in the Florida Supreme Court. Hall was “functionally illiterate and has the short-term memory of a first-grader,” the dissenting opinion observed.

In nine separate IQ tests conducted throughout the years, Hall’s scores ranged from 60 to 80. Before one crucial hearing, he scored a 71.

The Supreme Court has previously decided, in the 2002 case Atkins v. Virginia, that executing those variously called mentally retarded or intellectually disabled violates the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment. The court left the definition up to individual states.

“No legitimate penological purpose is served by executing a person with intellectual disability,” Kennedy wrote in the decision issued Tuesday. “To impose the harshest of punishments on an intellectually disabled person violates his or her inherent dignity as a human being.”

Florida imposes a three-part test, which under a state court ruling effectively starts with a rigid requirement that the inmate score 70 or below on the IQ test. If the inmate scores below the cutoff number, the state also will assess for “deficits in adaptive behavior” and an onset before age 18.

Medical professionals, Kennedy stressed Tuesday, consider an IQ test score to represent a range rather a fixed point. Test scores may fluctuate from day to day, depending on the testing environment, the test-taker’s health, previous practice or other reasons.

The term “standard error of measurement” reflects the range that a single test score may represent. A score of 71, for instance, is generally considered to reflect a range of 66 to 76.

“An IQ score is an approximation, not a final and infallible assessment of intellectual functioning,” Kennedy wrote.

Seth Waxman, formerly the Obama administration’s solicitor general, argued on Hall’s behalf before the high court. Another one of Hall’s attorneys, Tampa-based Eric Pinkard, praised the ruling Tuesday, saying that “the court has recognized that intellectual disability is a condition, not a number, and that consequently Florida cannot ignore the standard error of measurement inherent in all IQ tests.”

Taking account of the standard error of measurement means that an IQ score of 71 to 75 would fall within the range of intellectual disability, which used to be called mental retardation.

Under the new ruling, Pinkard noted, these defendants would be able to present additional evidence of intellectual disability, including testimony concerning their difficulties in adapting.

Jenn Meale, a spokeswoman for Florida Attorney General Pam Bondi, said Tuesday afternoon that Bondi’s office was reviewing the court’s ruling.

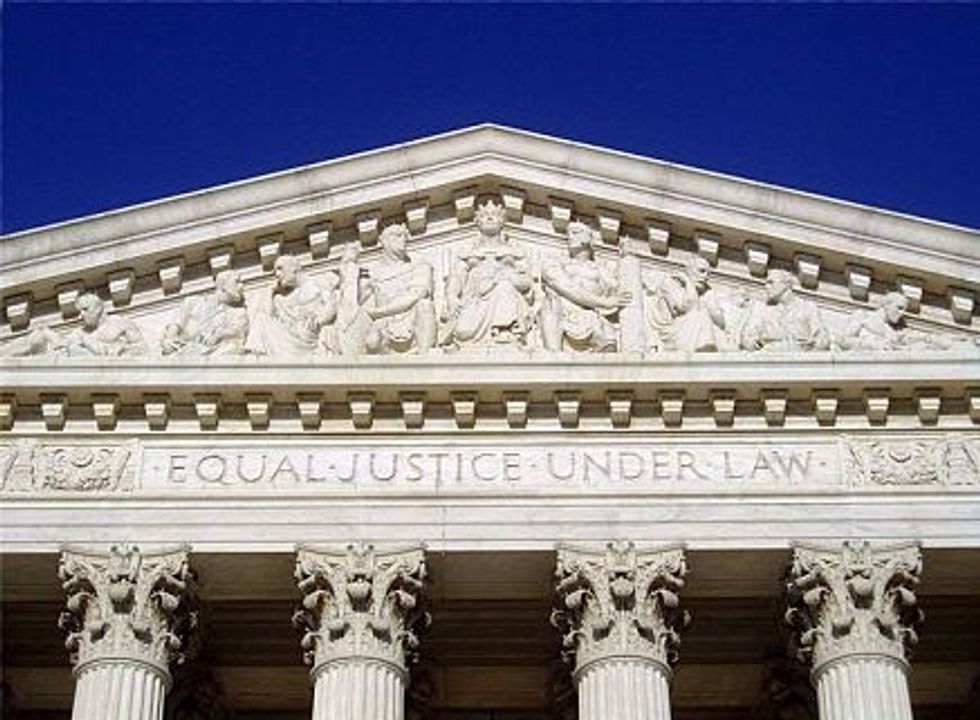

Photo: Matt H. Wade via Wikimedia Commons