Abuse Of Power Isn’t A Crime — But It Can Be An Impeachable Offense

“Was that wrong?” George Costanza asks in a 1991 episode of “Seinfeld” after his boss confronts him with a report that “you and the cleaning woman have engaged in sexual intercourse on the desk in your office.” George says he has to “plead ignorance,” because no one “said anything to me at all when I first started here” suggesting “that sort of thing was frowned upon.”

Donald Trump’s legal team is trying out a version of the Costanza defense, arguing that the articles of impeachment against him are constitutionally deficient because they do not allege any violations of the law. That claim is so dubious that even Trump’s lawyers don’t believe it.

The president is accused of abusing his power for personal gain by pressuring the Ukrainian government to announce an investigation of a political rival. The scheme allegedly included temporarily blocking $391 million in congressionally approved military aid.

The Government Accountability Office recently concluded that Trump’s hold on that money violated the Impoundment Control Act. But the articles of impeachment do not mention that law or any other statute that Trump is accused of violating.

Is that a fatal flaw, as Trump lawyer Jay Sekulow and White House Counsel Pat Cipollone insist? Not according to George Washington University law professor Jonathan Turley, the sole Republican witness at the House Judiciary Committee’s Dec. 4 impeachment hearing.

Turley, who harshly criticized the impeachment process as rushed and incomplete, warned that abuse of power allegations can be dangerously amorphous when detached from the elements required to prove a crime. He nevertheless conceded that “the use of military aid for a quid pro quo to investigate one’s political opponent, if proven, can be an impeachable offense.”

Turley emphasized that “high crimes and misdemeanors” are not limited to statutory violations. The phrase “treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors,” he observed, “reflects an obvious intent to convey that the impeachable acts other than bribery and treason were meant to reach a similar level of gravity and seriousness (even if they are not technically criminal acts).”

Turley noted that James Madison, although he opposed including “maladministration” as grounds for impeachment, said the process was meant to address “the incapacity, negligence or perfidy of the chief Magistrate.” Alexander Hamilton likewise said impeachment was aimed at “those offences which proceed from the misconduct of public men, or, in other words, from the abuse or violation of some public trust.”

Harvard law professor Alan Dershowitz, a member of Trump’s legal team, now takes what he concedes is the minority position, arguing that an impeachable offense has to be a crime. But he was singing a different tune during Bill Clinton’s impeachment in 1998.

“It certainly doesn’t have to be a crime,” Dershowitz said on CNN. “If you have somebody who completely corrupts the office of president, and who abuses trust, and who poses great danger to our liberty, you don’t need a technical crime.”

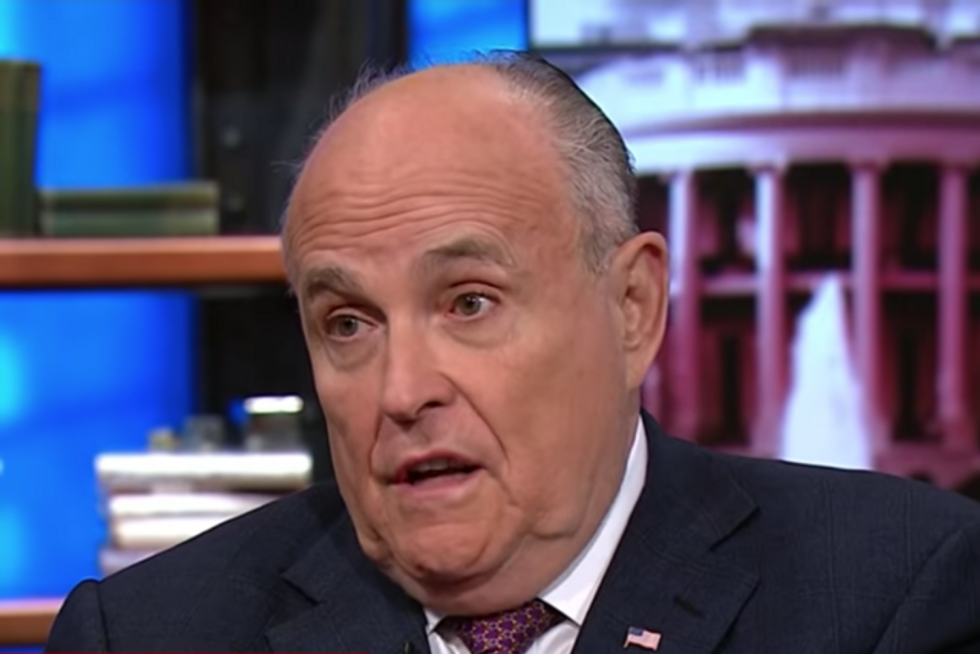

Another Trump lawyer, Rudy Giuliani, claims the articles of impeachment are unconstitutional because “abuse of power and obstruction of Congress are not crimes of any kind.” But during a 2018 discussion of Independent Counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation, Giuliani declared that a preemptive presidential self-pardon, while legal, “would just be unthinkable” and “would lead to probably an immediate impeachment.”

In other words, a self-pardon would not be a crime, but it would still be an impeachable offense. Similarly, a president who used his authority over the Justice Department to quash investigations of his friends and launch investigations of his enemies would be violating the public trust in a way that could justify impeachment, even if everything he did was technically legal.

Without a statutory basis, Sekulow and Cipollone argue, abuse-of-power charges effectively allow legislators to impeach the president because of policy disputes or partisan animus. But there is also a danger in letting a president off the hook because no one ever explicitly said his particular brand of misconduct was frowned upon.

Jacob Sullum is a senior editor at Reason magazine. Follow him on Twitter: @JacobSullum. To find out more about Jacob Sullum and read features by other Creators Syndicate writers and cartoonists, visit the Creators Syndicate webpage at www.creators.com.