To Save Americans From Starving, Congress Must Raise The Minimum Wage

Reprinted with permission from DC Report

Imagine Washington announcing today that for the next three decades your pay will increase each January. You'll get a boost to cover inflation plus 10-cents more an hour. That means your real pay next year, before taxes, will be $4 more per week.

Ask yourself, would you even notice an extra $4 a week in gross pay? Would you feel like playing by the rules and being a good worker was worth it?

Well, that's what has happened to the typical American worker since 1990, but no one announced it back then. And it's happened as unions have been pretty much destroyed, representing only about one in 15 private-sector workers.

As a middle-aged widow who lost her job and took minimum-wage work at a major national retailer to feed herself and her son, who live together in a town with low-cost housing, told me:

"You can't make ends meet on the minimum wage no matter how much you try. It is just not possible."

That's the prime reason Congress and President Biden must raise the minimum wage.

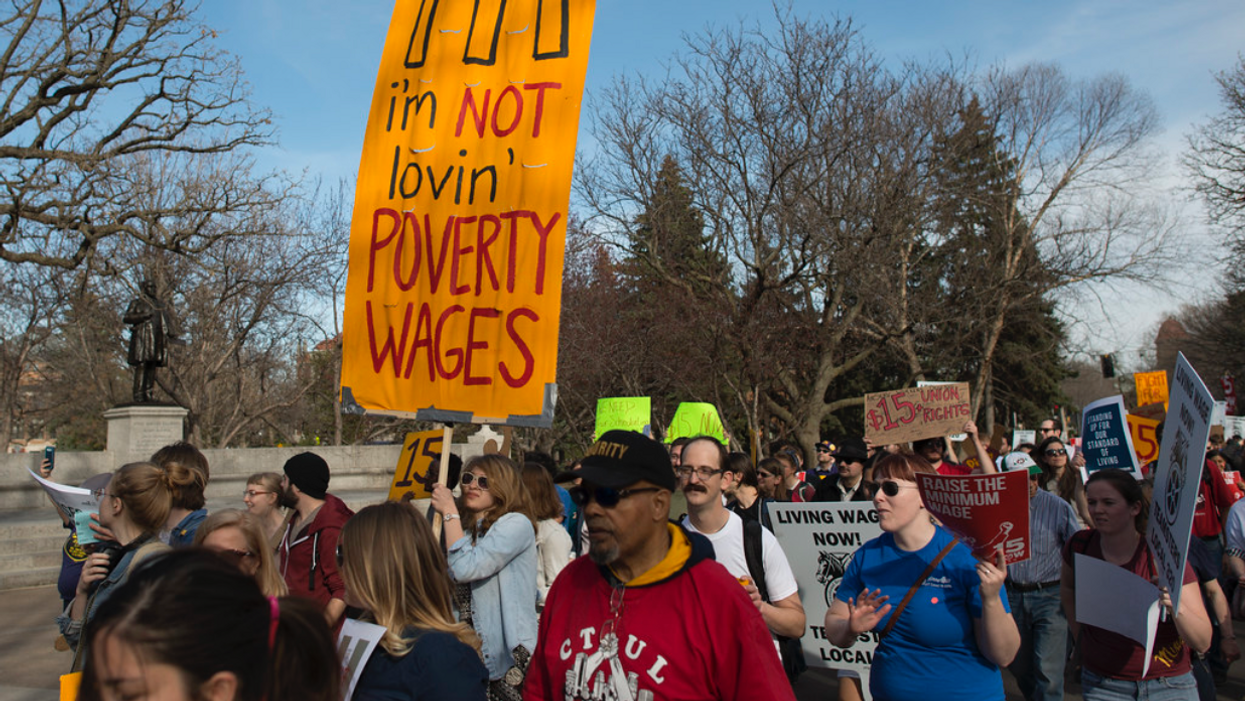

As private-sector unions have faded away, wages have fallen in tandem. The numbers and the pain of people like the widow show that Congress must step in, acting as a proxy union for the lowest-paid workers by raising the floor on wages in America. If lawmakers fail then taxpayers should expect rising costs for welfare to cope with social pathologies. We should all expect popular support for our tattered democracy will wither even more, putting our liberties in danger.

Inflation Toll

The story I pulled from the official data shows things are much worse than just the awful fact that the minimum wage has been stuck since 2009 at $7.25 an hour, its value being eroded by inflation even as America grows ever richer.

Each year, I do detailed analyses of W-2 wage and salary reports that employers send to the Social Security Administration. Its computers add up every filing and then a report shows how many people make how much in broad pay categories whether they had one employer or many.

What the wage data show is disturbing. America is becoming two nations separate and unequal, one with a minority of workers who are prospering, some making each year enough for a hundred families for a lifetime. Across the income divide more than 130 million workers struggle.

Republicans and some Senate Democrats claim that raising the minimum wage will kill jobs and force small businesses to close. That's not what past actual experience shows, at least not on this planet.

Faulty Argument

That argument is actually silly because it assumes that prices never increase so if wages go up businesses must fail. Nonsense. But should you find a dealer advertising new cars today at 1990 prices please let me know.

What the facts show that since 1990 our national wage pie, adjusted for inflation, has grown much bigger. Adjusted for inflation it was $8.8 trillion in 2019, up from $5 trillion in 1990.

But the way the wage pie was cut into slices changed significantly.

Let's look first at workers who always earn only the minimum wage. Such people exist, though they are not common.

In 1990 the minimum wage was $3.80. Adjusted for inflation it would have to have risen to $7.48 in 2019 just to stay even. But the minimum wage was only $7.25, the same as today. In absolute terms these workers are worse off, their meager slice of income pie shrinking.

In 2019 half of America's 169 million workers made less than $35,000; a third made less than $20,000. Only one in three workers earn more than $1,000 per week.

$620 a Week

What about the typical worker? That's measured by examining median pay; half make more, half less. In 2019 the median wage was $34,250 or $620 a week.

That's a real increase since 1990 of $5,712. That sounds good until you realize that in round numbers it works out to that dime an hour raise every January.

How about the average wage which includes those with ginormous paychecks? Real average pay rose by $12,225 to $51,916. That's two dimes and a penny more per hour each January. How much would you notice an extra $8.40 a week – before taxes?

Now let's turn to the extremely well paid, people whose pay increases alone meant they gorged on wage pie while most everyone else got crumbs.

Let's consider all workers making $1 million or more, roughly one in every thousand workers. Their share of the national wage pie rose mightily, from 3 cents in 1990 to a nickel in 2019. That leaves everyone else with a smaller share of the pie to divvy up.

What about the super-paid workers who made $10 million or more in 1990 and 2019 using 2019 dollars?

More Super-Rich

The number of super-paid workers is for sure small. But it grew five-fold from 739 to 4,024.

Their average gross pay increased from just shy of $2 million to almost $2.5 million. Simply put in 2019 they got six days of pay for five days of 1990 work.

Also, a record 222 of these workers were paid more than $50 million in 2019, averaging $89 million each.

Even if we assume that employers pay these top earners what they are worth, a society whose rules and regulations lavish every more pay on those to the top while hardly growing wages for two-thirds or more of the workforce is neither stable nor enduring. The chasm between the super-paid and everyone else is huge and widening and can destroy support for democracy, as we saw with the failed coup on Jan. 6.

Without unions to bargain for workers pay simply is not going to improve. Indeed, our government has put downward pressure on wages through the welfare "reform" act President Bill Clinton signed, which flooded the market with women who have few job skills and little education, a stealth subsidy for many employers because they could pay less. The child tax credit for working parents has morphed over time into a subsidy for employers who now capture its benefits by not raising pay. Those are just of many anti-worker policies our government put in place during the past 40 years.

Congress can fix this. It has to step in as a proxy union for powerless workers and raise the minimum wage. If we could afford a minimum wage in the 1960s that's equal to about $12 an hour today then we can afford to raise our pay standards in today's much wealthier America.

And to those small businesses that say they will fold if they have to pay their workers more there is an answer: Raise prices.

If you can't afford to pay a living wage and you can't raise prices, your business is already failing so put it out of its misery. You can always start a new business in the future — and with people making more money your chances of success will be much better because more customers will have more money to spend.