Why Trump Must Think Twice Before He Gives A Pardon To Mike Flynn

Ever since Michael Flynn departed the Trump White House under a cloud of disgrace last February, speculation has mounted that the president might pardon his former national security adviser. With Flynn’s guilty plea in federal court and disclosure of his cooperation agreement with special counsel Robert Mueller, conjecture about such a pardon is rampant. And for Donald Trump, who clearly assumes that he can get away with anything, the appeal of silencing a potential witness with the pardon power must be almost irresistible.

But he should hesitate before pardoning anyone who might testify about him or members of his family.

By now it must be obvious even to Trump that a pardon for Flynn – or any Mueller defendant or target — would put the final touch on an obstruction of justice brief against him. It would complete a damning timeline that began when he fired FBI director James Comey, after he tried unsuccessfully to suborn Comey into dropping the nascent investigation of Flynn. Such a blatantly criminal abuse of power might even compel the cowardly House Republicans to consider impeachment.

If Trump thinks he would escape impeachment anyway, he should mull the problems he might face after leaving the White House. Regardless of his immunity from prosecution as president, a suspicious pardon would leave him legally vulnerable as soon as his presidency ends.

And if his lawyers doubt that, they should ask Bill Clinton about what happened after he pardoned Marc Rich, the infamous fugitive financier.

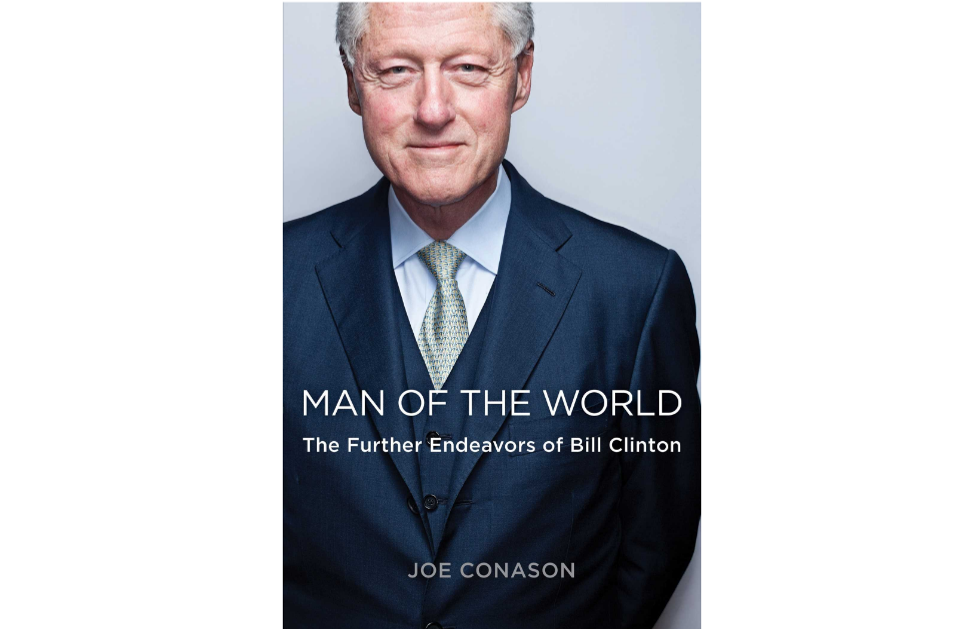

There was nothing corrupt about the Rich pardon, which President Clinton signed on January 20, 2001, his final day in office. But Clinton’s critics in the media, Congress, and his own Justice Department, and many Americans who followed the news coverage, suspected he had issued that writ in return for millions of dollars in campaign and foundation contributions from Rich’s ex-wife Denise. Actually, Clinton pardoned Rich because Ehud Barak, then Israel’s prime minister, had requested that favor three times during the final months of their protracted Mideast peace negotiations (as reported in Man of the World: The Further Endeavors of Bill Clinton, my book about his post-presidency, now in a paperback edition with a new afterword).

Among those most infuriated by the pardons was Mary Jo White, a Clinton appointee then serving as U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York. Less than a month later, on February 15, 2001, White announced that she had opened a criminal investigation. On ABC News’ Good Morning America, Washington correspondent Jackie Judd interviewed a Republican member of the Senate Judiciary Committee and former prosecutor who offered the prevailing theory of the case.

According to then-Senator Jefferson Beauregard Sessions (R-AL): “If a person takes a thing of value for themself [sic] or for another person that influences their decision in a matter of their official capacity, then that could be a criminal offense.” Now that Sessions is attorney general, perhaps he will explain to his apopleptic boss how such a theory of corruption would apply to the matter of a Flynn pardon – or any pardon Trump grants in a scheme to hinder the special counsel.

Three days after White’s announcement in February 2001, Clinton published a 1600-word New York Times op-ed denying any corrupt motive and defending the Rich pardon (without mentioning the entreaties from Barak, which only emerged as a result of the parallel Congressional investigation). Evidently the prosecutors were unpersuaded by Clinton’s argument, since they continued to investigate him as well as Denise Rich and other donors to the Clinton Foundation for more than three years.

By the time that the pardon probe officially folded – without any wrongdoing uncovered – its demise was quietly announced by White’s successor, a George W. Bush appointee named James Comey. Under the Clinton rules, which unofficially stipulate that any finding favorable to the former First Family receives little or no media attention, that announcement got almost no news coverage.

Yet despite the fact that federal prosecutors could make no case against Clinton, what remains is a bipartisan principle articulated by Mary Jo White and Jeff Sessions and pursued rigorously by Jim Comey: a corrupt pardon issued by a former president is fair game for criminal prosecution.

Trump can only ignore that jeopardy at his peril.