We’re Living ‘The Hunger Games’ — And We Need To Change That

Most of us are familiar with The Hunger Games — the story of a fictional future society where an elite has everything and is oblivious to the suffering all around them, beyond an occasionally peek at their ubiquitous screens to see the tragedies unfolding beyond their borders.

I founded Lions Gate Entertainment, which distributed that dystopian film to the world eight years ago. I never thought it would become a reality, but I’m afraid it has.

After spending three days in the Iraqi city of Mosul, where I was doing some desperately needed humanitarian work to help Christians terrorized by ISIS, I returned to my home in Vancouver. By habit, I opened my Instagram account and mindlessly browsed through postings of people I knew, to see what had happened while I was gone.

It was like leaving The Hunger Games’ District 13 and returning to the privileged life of Panem. As I gazed at photo-shopped selfies, hot vacation spots, and cute pets, I realized I just couldn’t connect with them. And I realized that most of the friends on my Instagram account couldn’t connect to the devastation I’d witnessed just hours before.

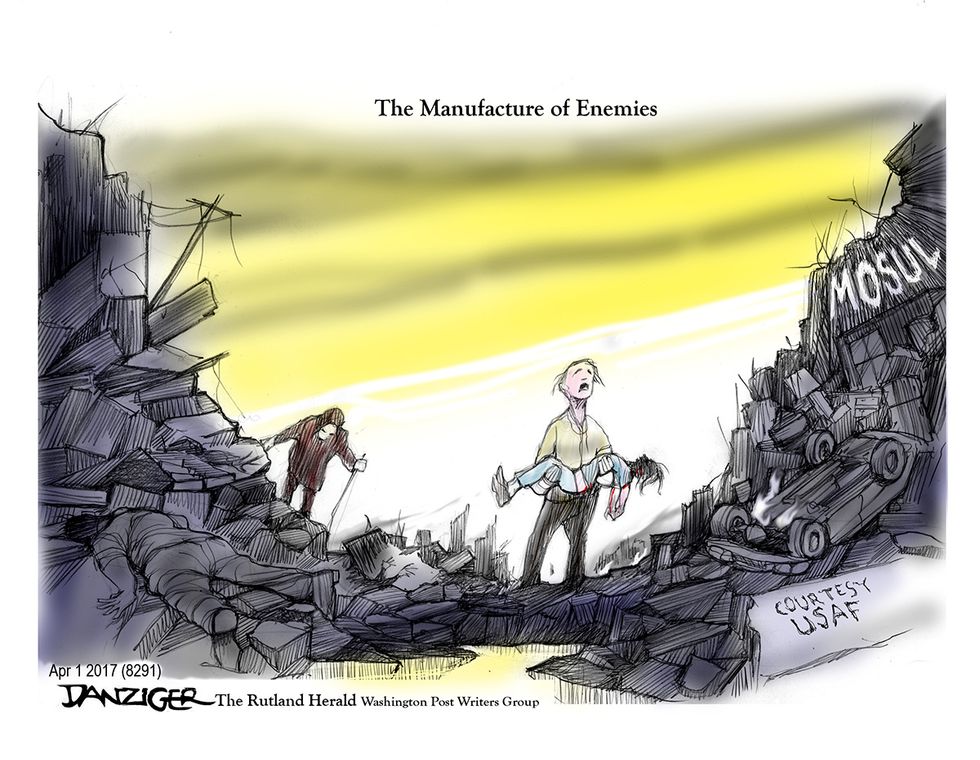

What I saw in Mosul was the aftermath of the nine-month battle to liberate the city, often called the birthplace of Christianity, from its ISIS captors — who had held the city’s civilians hostage for the preceding three years.

After the biggest urban battle since World War II, eight million tons of rubble is pretty much all that is left of the western part of this ancient city. It was mind-boggling to walk the streets, knowing there are still many undiscovered bodies buried beneath the bombed-out buildings. As many as 40,000 people may have died in the battle for Mosul. (Neither the Iraqi government nor the US coalition will acknowledge any total number of casualties).

Now in the safety of Vancouver, browsing through those Instagram photos, I realized that our society faces a profound challenge.

Don’t get me wrong. I don’t fault the folks who posted those pretty photos; I’ve posted plenty of my own. But we are in an existential crisis, absorbed with life in our comfortable, social-media driven bubbles, a phenomenon that isolates us from the world’s major challenges.

Until three years ago I was equally isolated. Then I visited Lesbos, Greece, and saw refugees landing on the beaches. That personal moment, which I could never have experienced on social media, motivated me to immerse myself in doing something to help the 65 million-plus human beings who are now refugees.

Since I began that work, I have grown increasingly frustrated that our social media addiction is making us like the citizens of The Hunger Games’ Panem — clueless to what is happening in the world around us.

But why?

Partly it is a matter of what media choose to cover — and what we choose to follow — in an era fueled by political scandal and celebrities. When was the last time you turned on any cable news outlet and saw a report about the thousands of civilians killed during the recapture of Mosul? Or a story about the millions of Yemenis now on the brink of starvation because of a US-backed, Saudi-led campaign against Houthi rebels in their country? How much coverage have you seen of the Russian-backed Assad regime’s brutal campaign against its own citizens that has killed hundreds of thousands and left half the population displaced?

My guess would be that you haven’t seen much.

But our growing isolation from these brutalities can’t be blamed only on the paucity of coverage, because media does provide some reporting of these tragedies. The broader problem is that we are being anesthetized by the technology now shaping our society and its discourse.

We increasingly get most of our information from social media, where we select the kind of information or opinions we want. To make matters worse, we allow the algorithms used by these platforms to reinforce our preferences and make those decisions for us. In this way, we can easily tune out the hard-core reality of what’s happening in the world.

Why should we care about what seems like an unstoppable trend? So what if we choose to exist in our comfortable bubble, paying little heed to the problems of people on the other side of the planet? We’re just civilians. We can’t fix wars, can we?

Perhaps not, but we should still worry about one very dangerous result of our intellectual and social isolation. Tyrants are now taking advantage of this public-interest vacuum to perpetrate astonishing atrocities against civilians, destabilizing whole societies and holding power — as the International Crisis Group outlined in its recent paper, Misery as a Strategy.

A dumbed-down public can be manipulated, fooled, and distracted more easily, allowing those in power to get away with murder, quite literally and on a massive scale. Robespierre said it best: “The secret of freedom lies in educating people, whereas the secret of tyranny is in keeping them ignorant.”

While we live in a world where the rules of conduct are melting away at a dizzying pace, there is a solution to this growing entropy on the international stage. We must change our social media behavior.

Accompanying me in Mosul was my friend, the global philanthropist Amed Khan. One of his ideas is to invite Vice President Mike Pence to come to Mosul and witness the plight of Christians there. We can hope that Pence and other leaders will take Amed up on that invitation.

But I would extend it even further.

We don’t have to give up Instagram or any other platform. But we do need to log off from time to time, to take personal responsibility to engage with the world beyond the screen. When we choose to live within an isolated bubble, allowing barbarism to prevail, everyone will lose eventually.

The Hunger Games teaches us that, too.

Founder of the Radcliffe Foundation, which sponsors his continuing work on refugee issues, Frank Giustra is the former chair of Yorkton Securities and the co-founder of Lionsgate Entertainment. He is also an active executive member of the International Crisis Group and created the Clinton Giustra Enterprise Partnership with former president Bill Clinton.

IMAGE: Displaced Iraqi civilians who fled Mosul gather at Khazer camp, Iraq December 13, 2016. REUTERS/Ammar Awad