Caught In A Lie? Maybe Oxytocin Is To Blame

By Karen Kaplan, Los Angeles Times

LOS ANGELES — There are lies, damn lies — and the lies that we tell for the sake of others when we are under the influence of oxytocin.

Researchers found that after a squirt of the so-called love hormone, volunteers lied more readily about their results in a game in order to benefit their team. Compared with control subjects who were given a placebo, those on oxytocin told more extreme lies and told them with less hesitation, according to a study published Monday in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

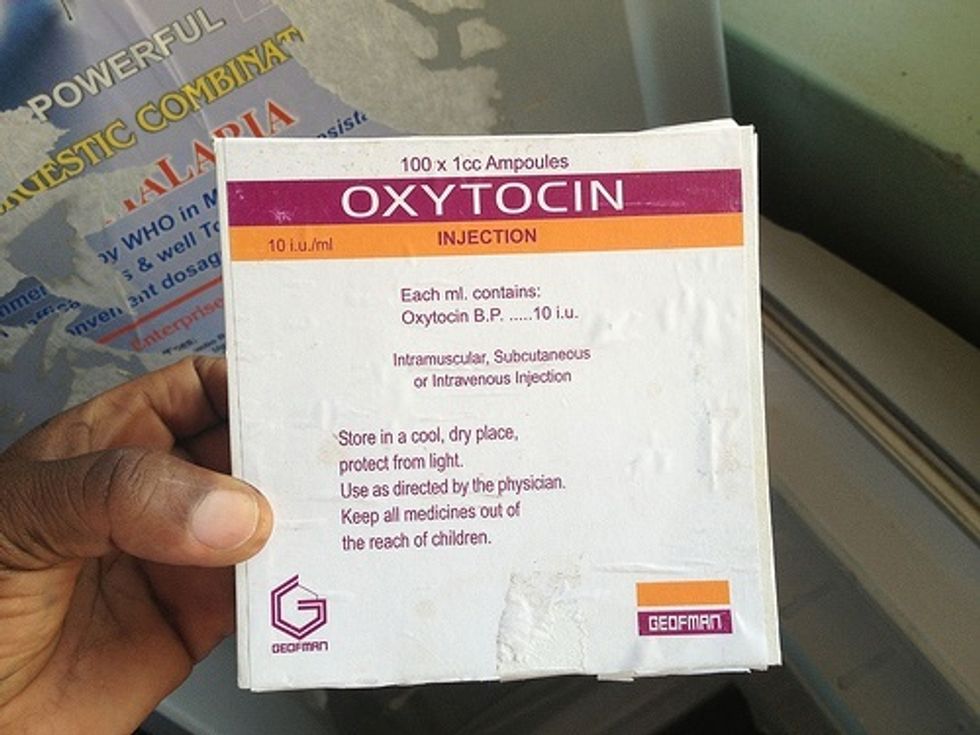

Oxytocin is a brain hormone that is probably best known for its role in helping mothers bond with their newborns. In recent years, scientists have been examining its role in monogamy and in strengthening trust and empathy in social groups.

Sometimes, doing what’s good for the group requires lying. (Think of parents who fake their addresses to get their kids into a better school.) A pair of researchers from Ben-Gurion University of the Negev in Israel and the University of Amsterdam figured that oxytocin would play a role in this type of behavior, so they set up a series of experiments to test their hypothesis.

The researchers designed a simple computer game that asked players to predict whether a virtual coin toss would wind up heads or tails. After seeing the outcome on a computer screen, players were asked to report whether their prediction was correct or not. In some cases, making the right prediction would earn a player’s team a small payment (the equivalent of about 40 cents). In other cases, a correct prediction would cost the team the same amount, and sometimes there was no payoff or cost.

In the first round, 60 healthy men sprayed either a small dose of oxytocin or a placebo into their noses 30 minutes before playing the game. As expected, men in both groups cheated — but the men who had taken the oxytocin cheated more.

By definition, anyone’s coin-toss predictions should be correct 50 percent of the time, on average. But the players on oxytocin said they made the right prediction 79.7 percent of the time, as did 66.7 percent of the players on the placebo.

What’s more, players on the hormone reported on the accuracy of their predictions in an average of 2.22 seconds. That was significantly faster than the players on the placebo, who took 2.86 seconds to decide what to tell the researchers. Apparently, the decision to lie to benefit the group required less deliberation than the decision to tell a self-serving lie.

In cases where correct predictions led to either no gain or a loss, oxytocin didn’t seem to induce players to lie any more than they would have otherwise, the researchers found.

In the next round of the experiment, the rules of the game were basically the same except that the gains (and losses) were kept by the players, not shared with a team. In that case, there was no difference in lying, truth-telling or response time based on whether players got oxytocin or the placebo. The study authors interpreted that as evidence that oxytocin influences only group dynamics, not individual behavior.

The researchers paid special attention to cases of “extreme” lying — players who said nine of their 10 predictions were correct. In truth, people should do that well only 1 percent of the time. But in the game, 53 percent of the men who got oxytocin said they went nine for 10 when they were playing for a team. Not only was that higher than the 23 percent of men who told the same whopper after getting the placebo, it was also higher than the 33 percent of men who told that lie under the influence of oxytocin when they were playing only for themselves.

“When dishonesty serves group interests, oxytocin increased lying as well as extreme lying,” the researchers concluded. “When lying served personal self-interests only, oxytocin had no effects.”

Photo: Monash University via Flickr