Why More States Should (Finally) Ban the Death Penalty

Most of the civilized world has come to regard killing someone held in captivity as barbaric. The death penalty has been abolished in the European Union and 19 U.S. states. Governors in four states that do permit capital punishment — Colorado, Oregon, Pennsylvania and Washington — have imposed a moratorium on executions.

The rest of America is getting there. For the first time in almost 50 years, less than half the public supports the death penalty, according to a new Pew Research Center survey. Even states that still put inmates to death seem to be losing the stomach for it. The United States is set to carry out fewer executions this year than it has since the early ’90s.

This November, voters in two very different places, Nebraska and California, will have an opportunity to remove state-sanctioned killing from their books. (Going the other way, a referendum in Oklahoma calls for amending the state constitution to protect the use of the death penalty.)

The most heated battle over the death penalty has taken place in Nebraska. It’s also the most significant one, for it shows how conflicted even conservative Americans have become over the practice. In fact, Nebraska hasn’t performed an execution in nearly 20 years. Conservatives in red states such as Missouri, Kentucky, Kansas, Wyoming and South Dakota, meanwhile, have sponsored bills to end the death penalty.

In Nebraska, lawmakers from both parties voted last year to eliminate the death penalty and replace it with mandatory life in prison for first-degree murder. Nebraska’s pro-capital punishment governor, Pete Ricketts, vetoed the bill. The legislature overturned the veto.

Ricketts then pushed a successful petition drive to put the matter on the ballot. Nebraskans will vote on whether to accept the legislature’s decision to strike the death penalty and instead require life without parole.

The outcome is hard to predict. “In certain issues, particularly with a populist strain, Nebraska is not nearly as doctrinaire conservative as people might think,” Paul Landow, professor of political science at the University of Nebraska Omaha, told me.

Ernie Chambers, a progressive from Omaha and the longest-serving state senator in Nebraska history, has introduced a measure to repeal the death penalty 37 times. “That kind of persistence has left an indelible mark on the issue,” Landow noted.

In California, a ballot measure to end the death penalty failed four years ago. This time, there are two referendums that seem at odds with each other. One would abolish the death penalty. The other would speed up the appeals process and thus hasten executions.

The case against the death penalty is well-known by now. Capital punishment exposes a state to the moral horror of killing an innocent person. Over the past 40 years, some 156 people on death row have been exonerated, many with the help of DNA evidence.

Citing church doctrine on the sanctity of life, the Nebraska Catholic Conference is urging voters to retain the repeal of the death penalty. One who opposes abortion on “pro-life” grounds, its argument goes, must also oppose the death penalty.

There’s little evidence that the death penalty deters murder. That leaves the questionable value of retribution — that erasing the monster who committed a heinous crime will bring comfort to the victims’ loved ones.

More and more survivors are countering this line of reasoning. Despite having suffered immeasurably, they hold that executing the criminal would just add to the toll. The state would somehow be justifying the crime of murder by committing it.

The movement away from capital punishment is clearly gathering force. This is one good direction in which our history is moving.

Follow Froma Harrop on Twitter @FromaHarrop. She can be reached at fharrop@gmail.com. To find out more about Froma Harrop and read features by other Creators writers and cartoonists, visit the Creators webpage at www.creators.com.

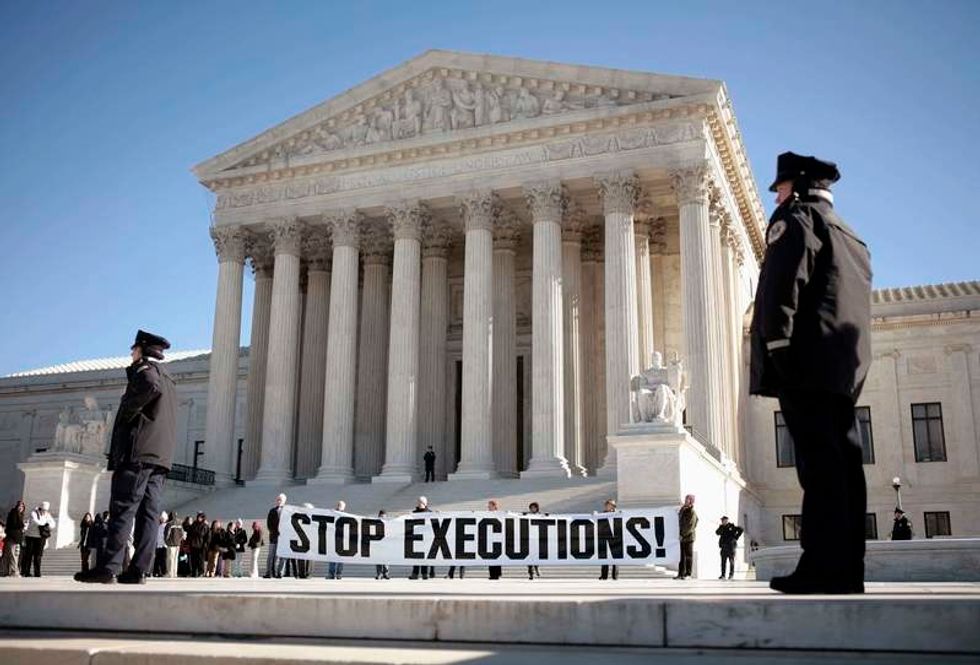

FILE PHOTO: Protesters calling for an end to the death penalty unfurl a banner before police arrest them outside the U.S. Supreme Court in Washington January 17, 2007. REUTERS/Jason Reed/File Photo