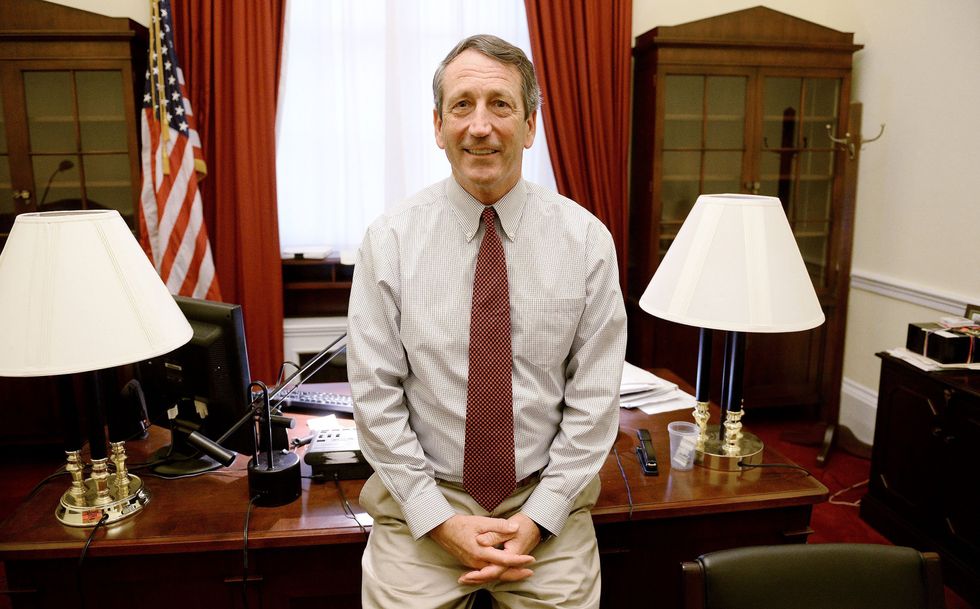

Five Years After ‘Appalachian Trail’ Scandal, Sanford Rises From Political Dead

By James Rosen, McClatchy Washington Bureau

WASHINGTON — During a break in the recent congressional session, Mark Sanford sidled up to his pal Mick Mulvaney and sat next to him on a back bench in the ornate chamber of the U.S. House of Representatives, a Cheshire cat’s grin on his lean face.

When Mulvaney made Sanford wait a few moments in silence, the former South Carolina governor couldn’t help himself.

“Notice anything different?” Sanford asked.

Mulvaney panned Sanford up and down, then exclaimed with exaggerated surprise:

“Marshal Sanford, you’ve bought yourself a new suit!”

The notoriously skinflint Sanford, a man of considerable means who wore a sports coat with an open-neck shirt to his own gubernatorial inauguration ball, couldn’t help himself.

“Paid $129 for it,” he said.

For Mulvaney and other Sanford friends, the new suit is a small but telling sign that he’s been, as he claims, humbled by the spectacular fall he took from the edge of national political power thanks to a sexy Argentine mistress, a tearful confession to the extramarital affair on national television, and a claim in subsequent days that he’d met his “soul mate.”

Sanford, who noted several times in a recent interview that he’s the only former governor in the House, no longer insists on doing everything his way and only his way. The onetime loner now watches college football games on Saturdays with other lawmakers. In his hometown of Charleston, S.C., and in the surrounding 1st Congressional District, he lingers with constituents, trades small talk, and shows interest in their families and their lives.

All this might not be newsworthy, save for one bizarre interlude in Sanford’s past: Five years ago, while serving as governor, he abruptly disappeared.

For six days, no one — not his wife or four sons, not his aides, not the Statehouse reporters who covered his every move — knew where he was. His chief of staff left 15 unanswered messages on his cellphone. His spokesman told baffled reporters that he was “hiking the Appalachian Trail.” Fellow Republicans said his absence was irresponsible.

In just a few days, the odd case of the missing governor became a huge news story.

Finally, on June 24, 2009, Sanford resurfaced. Political reporter Gina Smith, acting on a tip that The State newspaper in Columbia, S.C., had received, was waiting for him at the Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport when he got off a flight from Buenos Aires.

Sanford told Smith that he’d been in Argentina and, at a nationally televised news conference later that day, he admitted to the affair.

He resigned as the chairman of the Republican Governors Association — a post many assumed he’d use as a steppingstone to a White House run — but served out his term as governor into January 2011, despite calls for his resignation.

Disgraced and discredited, Sanford disappeared again; this time, most observers thought, for good. But again Sanford surprised everyone, joining Congress in May 2013 via a special election.

Sanford’s rise from the political dead was made possible by a fluke. When South Carolina Republican Sen. Jim DeMint abruptly retired in January 2013 to take over the Heritage Foundation, Washington’s leading conservative think tank, Gov. Nikki Haley promoted then-Rep. Tim Scott to replace him in the Senate, forcing a special election for Scott’s House seat.

It happened to be the same Charleston-based seat Sanford had held for six years in the 1990s before he left Congress to fulfill a term-limit pledge.

Mulvaney, who was a state legislator for the second half of Sanford’s stint as governor from January 2003 to January 2011, backed another candidate in last year’s crowded Republican primary for that election.

Mulvaney thought that the whole sordid scandal surrounding Sanford would become a debacle for Republicans should the former governor rejoin Congress. His fears deepened after Sanford dropped by the home of his ex-wife, Jenny Sanford, to watch the Super Bowl with his son and she charged him with trespassing.

That dust-up led the National Republican Congressional Committee to pull its ads and other support from Sanford’s race.

“The last thing I wanted was for Mark Sanford to be the face of the Republican Party,” Mulvaney told McClatchy.

But since Sanford emerged from a crowded Republican primary, easily won the general election and came to Washington last year, Mulvaney has been pleasantly surprised.

“He has focused on issues. He hasn’t made himself into a spectacle. He’s working on his committees,” Mulvaney said. “He’s trying really hard to do something that does not come naturally to him: putting time into personal relationships.”

___

When former President Ronald Reagan, an iconic figure to conservatives, died in 2004, South Carolina state Sen. John Courson delivered the eulogy at a memorial service in Columbia, the capital. He’d been a delegate for Reagan at three presidential conventions.

With Sanford, governor for less than 18 months, sitting in the front row, Courson told the mourners that their tall and lean chief executive with the conservative views was Reaganesque and could one day become president. But over the next half-dozen years, as Courson experienced Sanford’s aloofness and perennial tangling with legislators, his view changed.

As deeply conservative as Reagan was, he was willing to accept three-quarters of what he wanted and call it a victory. Sanford rarely bent, and he lambasted his peers even when they were willing to give him 90 percent of his agenda. He also seemed to relish the confrontation.

As governor, Sanford once took piglets into the Statehouse lobby between the South Carolina House and Senate chambers to illustrate wasteful spending, infuriating fellow Republican legislators who saw themselves as frugal. Now, back in Washington, Sanford is trying to keep a low profile and steer clear of anything that might smack of a flamboyant stunt. He’s largely succeeded, save for the time last July when an unexpected House vote forced him to make a mad dash from the National Mall, where he’d been jogging, to cast his ballots wearing shorts, a T-shirt, gym socks, and sneakers.

His former mistress, Maria Belen Chapur, is now his fiancee. The onetime Argentine TV reporter set off a hundred camera flashes last year when she showed up at Sanford’s side in Charleston for primary and general election victory bashes.

“When we’re together, we live together,” Chapur told a Buenos Aires TV station in a rare interview. “Partly in Washington, partly in Charleston.”

Despite the difficulties, Chapur said she was happy being with the congressman.

Saying he’s been “saved by my God,” Sanford is doing a yearlong devotional, each day reading an inspirational religious reflection in a book called “Streams in the Desert.” He often quotes Bible passages. A favorite is Matthew 7:1-2, which says, “Do not judge, or you too will be judged. For in the same way you judge others, you will be judged, and with the measures you use, it will be measured to you.”

“I spend a lot less time these days casting judgments on others,” Sanford said. “There is some tempering of any human soul if you go through a big storm, and I went through a big storm in 2009.”

Five years later, South Carolina state Sen. Tom Davis views Sanford’s resurrection of a political career that many had given up for dead as a peculiarly American morality tale. Davis, who was the chief of staff for Sanford when he was governor and remains a close friend, said Sanford won election to Congress because his constituents believed that he was deeply sorry for his past personal failings.

“The American people are forgiving people,” Davis told McClatchy. “They want true contrition and true atonement.”

Gina Smith of the Island Packet in Hilton Head, S.C., contributed to this report.

Photo: Abaca Press/MCT/Olivier Douliery

Interested in U.S. politics? Sign up for our daily email newsletter!