By Victoria Kim and Joel Rubin, Los Angeles Times (TNS)

LOS ANGELES — When the makers of the HBO documentary The Jinx discovered an old letter that appeared to link New York real estate scion Robert Durst to a Los Angeles killing, their first instinct was to keep it from authorities.

They locked the letter away in a bank safe deposit box and strategized how to confront Durst with it.

“Nobody is going to know that we have this document,” director Andrew Jarecki says on camera to members of his film crew. “We interview Bob, we bring it up, we have it on film, and now we have something that the LAPD is going to really want because … we’ve got Bob reacting clean to this hugely important piece of evidence.”

The scene made for gripping television and left no doubt that a key piece of evidence implicating Durst was inextricably tied to the six-part television series.

As Los Angeles prosecutors filed murder charges against Durst on Monday, it remained an open question how much of the evidence uncovered in the documentary, which also included arguably incriminating statements by Durst, will make its way into the courtroom.

Legal experts said the prosecution probably will try to limit how much it relies on the documentary in order to keep Durst’s defense team from raising doubts about the film’s accuracy and from challenging the unusual role the filmmakers played in building the case against Durst.

For their part, the filmmakers said they expect they will be called as witnesses, and they canceled a raft of planned interviews, saying it would be inappropriate to comment.

The documentary and the questions it raises loomed in the background Monday as Durst remained in a New Orleans jail after his arrest there Saturday.

Wearing an orange jail suit, Durst appeared before an Orleans Parish magistrate and waived his right to fight extradition to California.

“Fighting extradition when you’re already in the U.S. makes no sense,” Chip Lewis, one of Durst’s attorneys, told the Los Angeles Times before the court hearing.

When Durst will arrive in Los Angeles is unclear. Louisiana officials announced late Monday that he had been booked on two weapons-related charges: being a convicted felon in possession of a firearm and possession of a weapon with a controlled dangerous substance. The substance was a small amount of marijuana, a Louisiana State Police spokeswoman said.

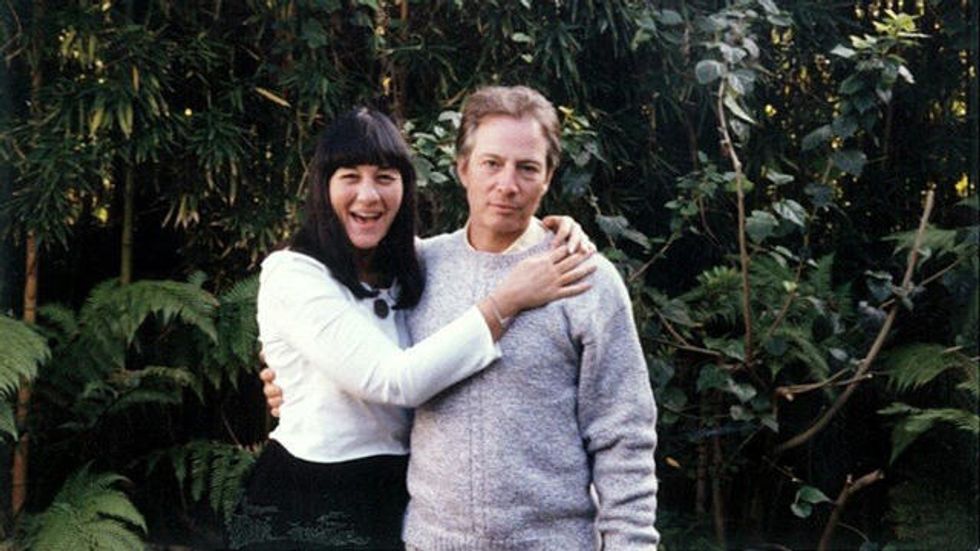

In Los Angeles, Durst is accused of the execution-style killing of a friend, Susan Berman, in her Benedict Canyon home in December 2000. At the time Berman was killed, New York authorities were planning to interview her to learn what she knew about the 1982 disappearance of Durst’s first wife, Kathleen.

The charges include allegations that Durst lay in wait and killed Berman because she was a witness to a crime. Durst could face the death penalty if he is found guilty.

Los Angeles police rejected any suggestion that the timing of last weekend’s arrest was influenced by the HBO documentary.

“We based our actions on the investigation and the evidence,” Los Angeles Police Department Deputy Chief Kirk Albanese said. “We didn’t base anything we did on the HBO series. The arrest was made as a result of the investigative efforts and at a time that we believe it was needed.”

Sunday’s finale of The Jinx revolved largely around the letter, which Durst wrote to Berman the year before she was killed. In the documentary, Jarecki zeroes in on similarities between the handwriting on the letter’s envelope and an anonymous note sent to Beverly Hills police at the time of Berman’s killing that alerted them to “a cadaver” in her house.

On both, Berman’s address was written in distinctive block handwriting, and the writer made the same mistake, misspelling the word “Beverly” as “Beverley.”

When confronted, a visibly shaken Durst admitted he penned the writing on the envelope to Berman but denied writing the note to police. He then left the interview to use the bathroom. Appearing not to notice that his wireless microphone was still recording, he is heard muttering to himself, “What the hell did I do? Killed them all, of course.”

“There it is, you’re caught,” he said at another moment. “What a disaster.”

Filmmakers said they provided investigators with the incriminating letter, which Berman’s stepson found in a box of her belongings, about two years ago, roughly the same time that prosecutors said they began reinvestigating the cold case with the LAPD.

The question of how LAPD detectives failed to discover the letter during their investigation into the murder turned an uncomfortable spotlight on the department. Asked for comment, Chief Charlie Beck declined, saying only that he hoped “that question and others will get answered in due time.”

Peter Arenella, a University of California, Los Angeles law professor and a nationally recognized expert on criminal law, said the timing of when the filmmakers began cooperating with police could become a thorny issue in a trial. If Jarecki and his team are viewed as having collaborated or assisted the police, they could be seen as having acted, if unwittingly, as agents of the government.

A judge then could rule that the interviews Jarecki did with Durst amounted to “unreasonable questioning and de facto interrogation” by the government, Arenella said. That could be grounds for Durst to claim his constitutional rights had been violated and that his statements should not be admitted as evidence.

Unaired footage Jarecki shot during interviews with Durst or others that did not make it into the final cut of the documentary could become a point of contention in the case, said Loyola Law School professor Stan Goldman, an expert on criminal procedure and evidence issues.

If prosecutors want to use Durst’s aired comments at trial, Durst’s attorneys probably will seek to review the unaired material to build their defense and explore whether the filmmakers presented any information in a misleading way or omitted favorable information about their client, Goldman said.

Close watchers of the documentary have already raised questions about whether Jarecki misrepresented for dramatic effect the timing of the climactic interview in which he confronts Durst with the letter.

In the documentary, Jarecki appears to persuade a reluctant Durst to sit for the interview by leveraging the possibility of sharing footage he shot of Durst in 2013 that Durst wanted to use in a legal proceeding. However, Jarecki and producer Marc Smerling said in interviews that the final confrontation with Durst took place in 2012. Jarecki also gave reporters differing answers to the question of how much time passed before an editor belatedly discovered Durst’s bathroom comments.

Goldman cited Michael Jackson’s 2005 criminal trial in Santa Barbara, Calif., on child molestation charges, in which defense attorneys used outtakes of British TV interviewer Martin Bashir’s documentary to make the case that Jackson had been unfairly portrayed as a pedophile.

That documentary, Goldman recalled, “included fragments of any sentence that made him sound guilty.”

The late pop singer’s defense attorneys closed their case by playing outtakes from the documentary that they believed showed Jackson in a different light.

If Jarecki and HBO executives refuse to hand over unaired footage from The Jinx, Goldman said, material that did air in the documentary could be excluded from the trial as well, including the bathroom comments. A judge, he said, is unlikely to allow prosecutors to present the documentary without also giving defense attorneys the opportunity to evaluate the context in which the statement was made.

But he and Arenella said Durst and his lawyers would be on weak legal ground trying to argue that a jury should not hear the bathroom mutterings because they were made in private. Arenella said a judge would probably rule that Durst had no expectation of privacy because he had signed a legal waiver allowing the filmmakers to use his comments.

“I think it’s very likely that it’ll end up before a jury,” Arenella said.

___

Staff writers Molly Hennessy-Fiske, Richard Winton and Kate Mather contributed to this report.

Robert Durst, a wealthy New York real estate heir, has been arrested and charged with the murder of his friend Susan Berman. The crime was allegedly commited by Durst inside this Beverly Hills home in 2000. (Francine Orr/Los Angeles Times/TNS)