Forgotten Lessons Led To Tragedy In Afghanistan

The spectacle of Americans and their local allies rushing desperately to evacuate from Kabul brought to mind similar scenes from Saigon in 1975. The repetition suggested that Americans and their leaders didn't learn from the earlier experience. In fact, we did learn. But then we forgot.

Maybe the surprise is not that we had to rediscover the difficulty of extricating our people and allies after giving up on an unsuccessful war. Maybe the surprise is that there was such a long interval between the two debacles. For a while, we avoided such failures, and not by accident.

In the 1980s, liberals depicted President Ronald Reagan as a trigger-happy warmonger. But his two terms stand out as a time when the United States, haunted by Vietnam, largely rejected direct military intervention abroad. He did dispatch Marines to Beirut as part of a peacekeeping force — but when a terrorist attack killed 241 American service members, he quickly withdrew our forces.

Reagan's Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger laid out a set of principles for deciding when to go to war. He argued that "vital national interests" must be at stake and that we must have clear objectives and the means to attain them.

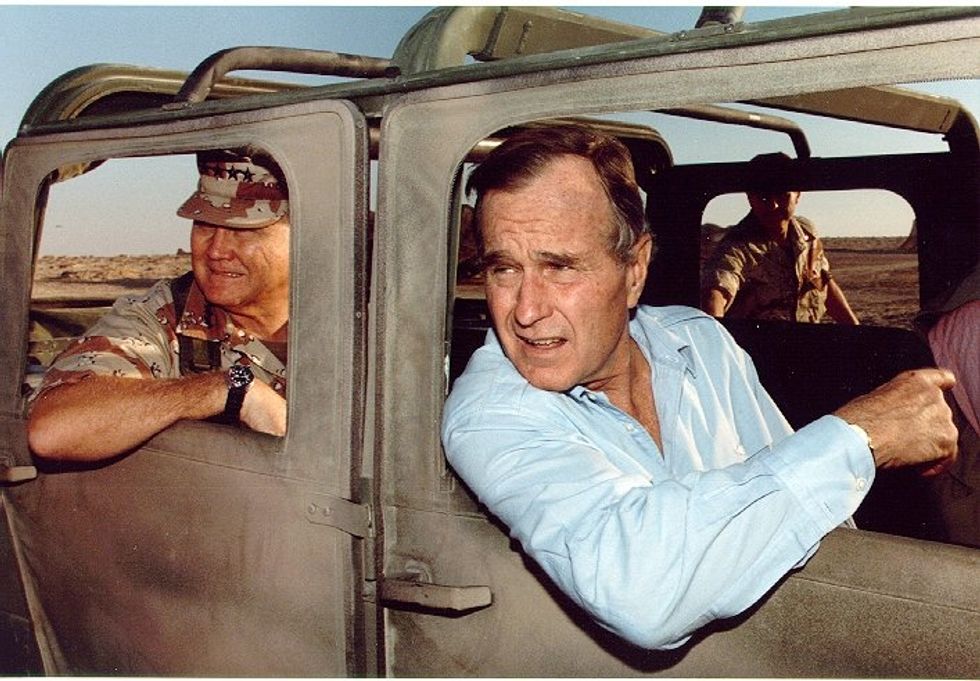

By 1992, the "Weinberger Doctrine" was incorporated into the "Powell Doctrine" by Gen. Colin Powell, who served President George H.W. Bush as chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Among his contributions was the rule that we have "a plausible exit strategy to avoid endless entanglement."

This approach didn't mean the U.S. would never go to war: We did so in 1983 in Grenada to topple a Marxist government and rescue American students. We did so in 1989 in Panama to remove a dictator blamed for drug trafficking. Most notably, we did so in 1991 to evict Saddam Hussein's army from Kuwait.

Whether these wars were wise and necessary is subject to debate. But in each case, we did what we set out to do and got out.

Success, however, bred amnesia. President George W. Bush had little choice but to invade Afghanistan after Osama bin Laden used it as a base for the 9/11 attacks. But once the Taliban were defeated and al-Qaeda was on the run, Bush chose to stay in an effort to cultivate freedom, democracy, and prosperity. It was the antithesis of the Powell Doctrine: an ill-defined mission that lay beyond our core competence and was not essential to our security — all without an exit strategy.

It has been clear for years that our efforts in Afghanistan were not working. But three presidents chose to prolong our involvement rather than admit futility.

What we learned when President Joe Biden refused to continue the war is that our failure exceeded our worst assumptions. We didn't know what was really going on in Afghanistan, and we didn't know we didn't know. We were clueless in Kabul.

The sudden, complete disintegration of the government revealed that it was no more viable than a brain-dead patient on life support. All Biden did was pull the plug.

It's fair to say that his administration should have been better prepared for the collapse so it could manage a more orderly withdrawal. But as Texas A&M security scholar Jasen Castillo tweeted, "There is no pretty way to leave a losing war." The nature of wars is that winners dictate the final terms. And the Taliban won this war.

It's commonly assumed that we could have preserved the previous status quo by maintaining a military presence in Afghanistan. But by May 2020, long before Biden arrived, the government had seen its control dwindle to 30 percent of the country's 407 districts, with the Taliban controlling 20 percent — more than at any time since the U.S. invasion.

Back then, one expert told Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, "The Taliban has so far been successful in seizing and contesting ever larger swaths of rural territory, to the point where they have now almost encircled six to eight of the country's major cities and are able to routinely sever connections via major roads." Sound familiar? The longer we stayed, the greater the risk of being forced into an even bigger commitment — with no hope of victory.

During the 2003 invasion of Iraq, Gen. David Petraeus said to a reporter, "Tell me how this ends?" Before we embark on a war, not after, is the time to answer that question. If we don't have an answer, the enemy will.

Follow Steve Chapman on Twitter @SteveChapman13 or at https://www.facebook.com/stevechapman13. To find out more about Steve Chapman and read features by other Creators Syndicate writers and cartoonists, visit the Creators Syndicate website at www.creators.com