CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla. (AP) — Atlantis and four astronauts returned from the International Space Station in triumph Thursday, bringing an end to NASA’s 30-year shuttle journey with one last, rousing touchdown that drew cheers and tears.

A record crowd of 2,000 gathered near the landing strip, thousands more packed Kennedy Space Center and countless others watched from afar as NASA’s longest-running spaceflight program came to a close.

“After serving the world for over 30 years, the space shuttle’s earned its place in history. And it’s come to a final stop,” commander Christopher Ferguson radioed after Atlantis glided through the ghostly twilight and landed on the runway.

“Job well done, America,” replied Mission Control.

With the shuttle’s end, it will be another three to five years at best before Americans are launched again from U.S. soil, with private companies gearing up to seize the Earth-to-orbit-and-back baton from NASA.

The long-term future for American space exploration is just as hazy, a huge concern for many at NASA and all those losing their jobs because of the shuttle’s end. Asteroids and Mars are the destinations of choice, yet NASA has yet to settle on a rocket design to get astronauts there.

Thursday, though, belonged to Atlantis and its crew: Ferguson, co-pilot Douglas Hurley, Rex Walheim and Sandra Magnus, who completed a successful space station resupply mission.

Atlantis’ main landing gears touched down at 5:57 a.m. sharp, with “wheels stop” less than a minute later.

“The space shuttle has changed the way we view the world and it’s changed the way we view our universe,” Ferguson radioed from Atlantis. “There’s a lot of emotion today, but one thing’s indisputable. America’s not going to stop exploring.

“Thank you Columbia, Challenger, Discovery, Endeavour and our ship Atlantis. Thank you for protecting us and bringing this program to such a fitting end.”

The astronauts’ families and friends, as well as shuttle managers and NASA brass, were near the runway to welcome Atlantis home. Difficult to see in the darkness, Atlantis was greeted with cheers, whistles and shouts. Soon, the sun was up and provided, finally, a splendid view. Within an hour, Ferguson and his crew were out on the runway and swarmed by well-wishers.

“The things that we’ve done have set us up for exploration of the future,” said NASA Administrator Charles Bolden Jr., a former shuttle commander. “But I don’t want to talk about that right now. I just want to salute this crew, welcome them home.”

Nine-hundred miles away, flight director Tony Ceccacci, who presided over Atlantis’ safe return, choked up while signing off from shuttle Mission Control in Houston.

“The work done in this room, in this building, will never again be duplicated,” he told his team of flight controllers.

At those words, dozens of past and present flight controllers quickly streamed into the room, embracing one another, wiping their eyes and snapping pictures.

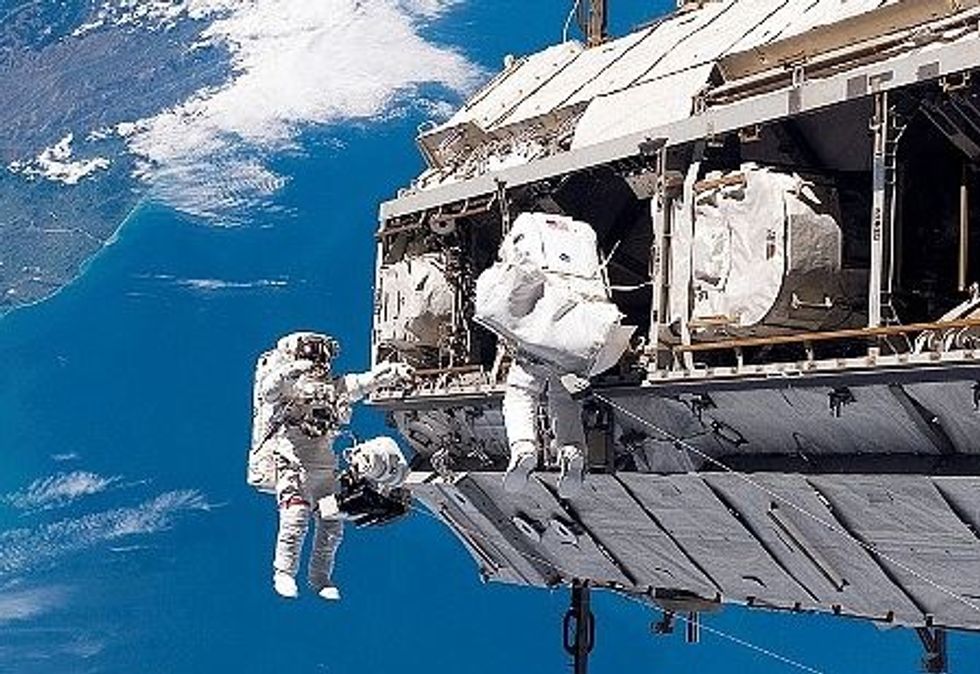

NASA’s five space shuttles launched, saved and revitalized the Hubble Space Telescope; built the space station, the world’s largest orbiting structure; and opened the final frontier to women, minorities, schoolteachers, even a prince. The first American to orbit the Earth, John Glenn, became the oldest person ever in space, thanks to the shuttle. He was 77 at the time; he turned 90 this week.

Born with Columbia in 1981, it was NASA’s longest-running space exploration program.

“I haven’t cried yet, but it is extremely emotional,” said Karl Ronstrom, a photographer who helps with an astronaut scholarship fund. He witnessed the first shuttle launch as a teenager and watched the last shuttle landing as a middle-aged man.

It was truly a homecoming for Atlantis, which first soared in 1985. The next-to-youngest in NASA’s fleet will remain at Kennedy Space Center as a museum display.

This grand finale came 50 years to the day that Gus Grissom became the second American in space, just a half-year ahead of Glenn.

Atlantis — the last of NASA’s three surviving shuttles to retire — performed as admirably during descent as it did throughout the 13-day flight. A full year’s worth of food and other supplies were dropped off at the space station, just in case the upcoming commercial deliveries get delayed. The international partners — Russia, Europe, Japan — will carry the load in the meantime.

It was the 135th mission for the space shuttle fleet, which altogether flew 542 million miles and circled Earth more than 21,150 times over the past three decades. The five shuttles carried 355 people from 16 countries and, altogether, spent 1,333 days in space — almost four years.

Two of the shuttles — Challenger and Columbia — were destroyed, one at launch, the other during the ride home. Fourteen lives were lost. Yet each time, the shuttle program persevered and came back to fly again.

The decision to cease shuttle flight was made seven years ago, barely a year after the Columbia tragedy. President Barack Obama nixed President George W. Bush’s lunar goals, however, opting instead for astronaut expeditions to an asteroid and Mars.

Last-ditch appeals to keep shuttles flying by such NASA legends as Apollo 11’s Neil Armstrong and Mission Control founder Christopher Kraft landed flat.

It comes down to money.

NASA is sacrificing the shuttles, according to the program manager, so it can get out of low-Earth orbit and get to points beyond. The first stop under Obama’s plan is an asteroid by 2025; next comes Mars in the mid-2030s.

Private companies have been tapped to take over cargo hauls and astronaut rides to the space station, which is expected to carry on for at least another decade. The first commercial supply run is expected late this year, with Space Exploration Technologies Corp. launching its own rocket and spacecraft from Cape Canaveral.

None of these private spacecraft, however, will have the hauling capability of NASA’s shuttles; their payload bays stretch 60 feet long and 15 feet across, and hoisted megaton observatories like Hubble. Much of the nearly 1 million pounds of space station was carried to orbit by space shuttles.

Astronaut trips by the commercial competitors will take years to achieve.

SpaceX maintains it can get people to the space station within three years of getting the all-clear from NASA. Station managers expect it to be more like five years. Some skeptics say it could be 10 years before Americans are launched again from U.S. soil.

An American flag that flew on the first shuttle flight and returned to orbit aboard Atlantis on July 8, is now at the space station. The first company to get astronauts there will claim the flag as a prize.

Until then, NASA astronauts will continue to hitch rides to the space station on Russian Soyuz spacecraft — for tens of millions of dollars per seat.

After months of decommissioning, Atlantis will be placed on public display at the Kennedy Space Center Visitors Complex. Discovery, the first to retire in March, will head to a Smithsonian hangar in Virginia. Endeavour, which returned from the space station on June 1, will go to the California Science Center in Los Angeles.

Ferguson said the space shuttles will long continue to inspire.

“I want that picture of a young 6-year-old boy looking up at a space shuttle in a museum and saying, ‘Daddy, I want to do something like that when I grow up.’ ”

AP writers Mike Schneider at Cape Canaveral and Seth Borenstein in Houston contributed to this report

Online:

NASA: http://www.nasa.gov/shuttle

Copyright 2011 The Associated Press.