Net Neutrality Regulations Released By FCC; Industry Lawsuit Expected

By Jim Puzzanghera, Los Angeles Times (TNS)

WASHINGTON — The Federal Communications Commission on Thursday publicly released the details of its new net neutrality regulations, which now will be pored over by broadband Internet service providers as they prepare for an expected legal challenge to the rules.

The 400-page order enacting the regulations was posted on the FCC’s website two weeks after it was approved on a partisan 3-2 vote by the Democratic-controlled commission.

The rules, crafted by FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler, change the legal classification of wired and wireless broadband, treating it as a more highly regulated telecommunications service in an attempt to ensure that providers don’t discriminate against any legal content flowing through their networks to consumers.

The decision to reclassify broadband under Title 2 of the telecommunications law, which has applied to conventional telephone service, was controversial even though Wheeler promised a light, modernized approach.

The FCC’s action was strongly opposed by AT&T Inc., Verizon Communications Inc., and other broadband providers as well as most Republicans.

AT&T hinted at a likely legal challenge of the regulations Thursday.

“Unfortunately, the order released today begins a period of uncertainty that will damage broadband investment in the United States,” said Jim Cicconi, the company’s senior executive vice president of external and legislative affairs.

“Ultimately, though, we are confident the issue will be resolved by bipartisan action by Congress or a future FCC, or by the courts,” he said.

Matt Wood, policy director of Free Press, a digital rights group that strongly supported tough net neutrality rules, said release of the order would end “fear-mongering” by opponents of the FCC’s action.

“Now that Congress and everyone else can read the rules, we can continue to have a debate about protecting free speech on the Internet,” he said.

“But we can dismiss the ridiculous claims from the phone and cable companies and their fear-mongering mouthpieces,” he said. “This is not a government takeover of the Internet or an onerous utility-style regulation.”

The actual new regulations take up just eight pages in the FCC’s order.

The main provisions prohibit broadband providers from blocking or slowing delivery of any lawful content for any reason other than “reasonable network management” and ban so-called paid prioritization, which would involve offering websites faster delivery of their content to consumers for a price.

The FCC could waive the ban on paid prioritization if a broadband provider or company could demonstrate it “would provide some significant public interest benefit and would not harm the open nature of the Internet.”

Most of the order was an explanation of the new regulations and the reasons for enacting them in hopes of withstanding a court challenge. Two previous FCC attempts to enact net neutrality rules were largely overturned by federal judges.

The last 87 pages of the order are statements from the five commissioners, including a 64-page dissent from Republican Commissioner Ajit Pai.

Pai and the agency’s other Republican commissioner, Michael O’Rielly, as well as key GOP members of Congress, unsuccessfully pushed Wheeler to release the entire proposal before the Feb. 26 vote.

But Wheeler did not, noting it was longstanding agency practice not to release draft proposals until they were approved by the commission.

In the two weeks since the vote, agency lawyers have been preparing the final version of the order.

It now will be published in the Federal Register in the next few weeks. Most of the rules will go into effect 60 days after that publication.

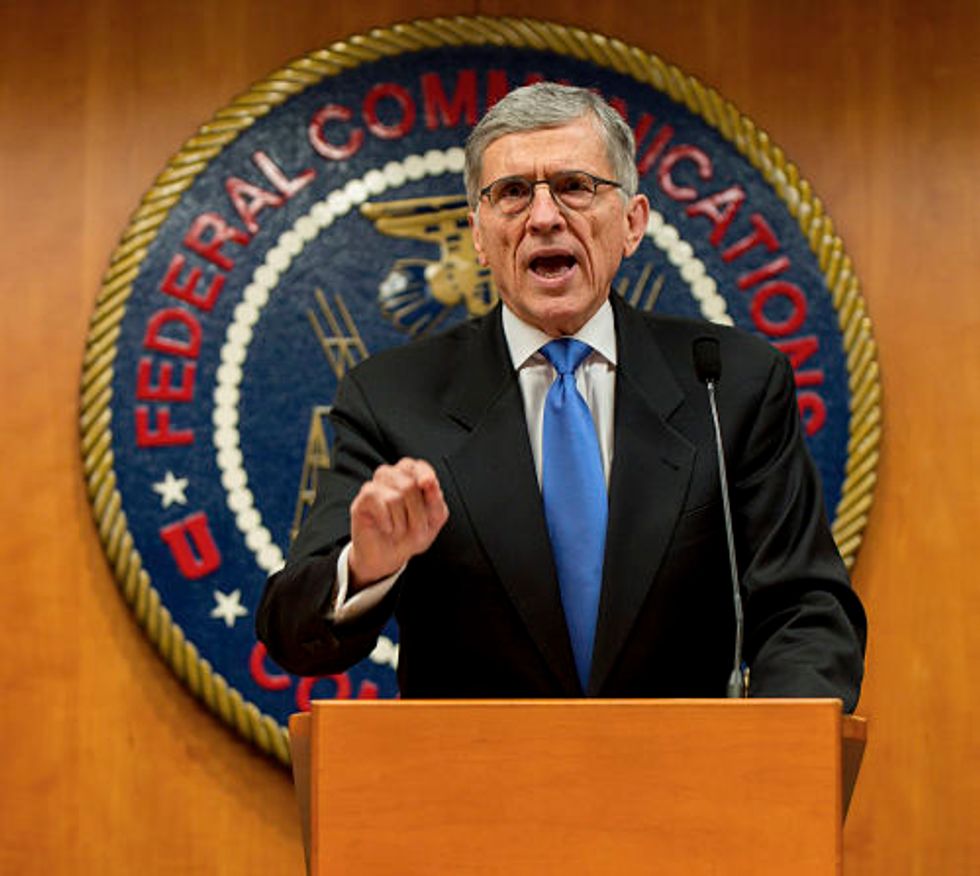

Photo: Federal Communications Commission staffers listen to statements being read during the FCC vote on net neutrality on Thursday, Feb. 26, 2015, in Washington, D.C. (Brian Cahn/Zuma Press/TNS)