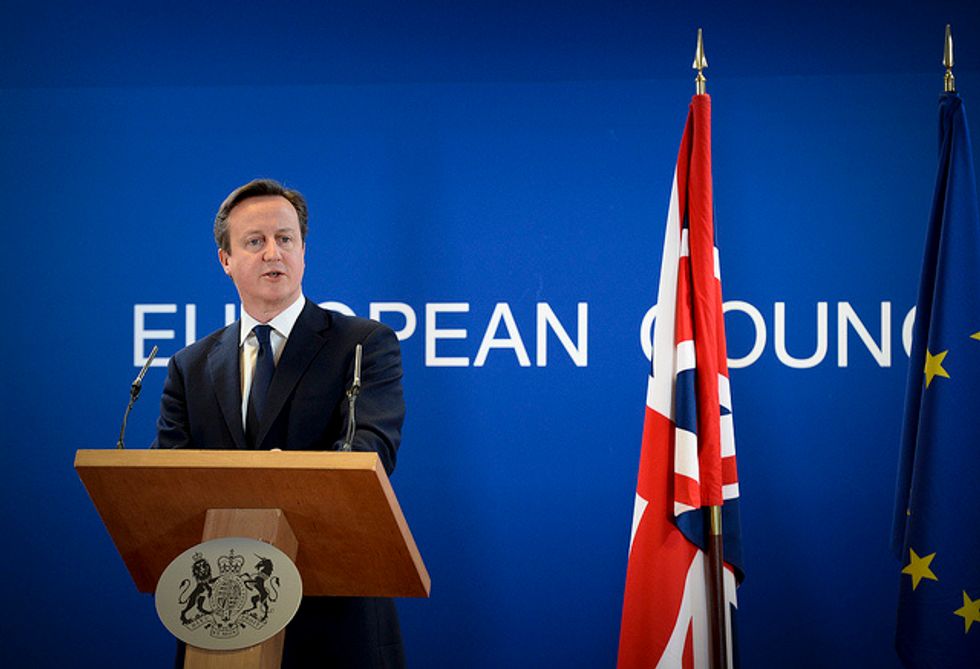

David Cameron’s Wizardry

WASHINGTON — Prime Minister David Cameron’s surprising success in winning an outright majority of seats in Britain’s Parliament is the result of a paradox: The center in Britain held and flew apart at the same time.

Neither the polls nor the pundits predicted the extent of Cameron’s triumph in Thursday’s voting. While they have something to answer for, their miscalculations also reflected the Conservative leader’s ability to translate a very modest increase in his share of the overall vote into many more additional seats than anyone thought possible.

On the latest count, Cameron’s Conservatives won just under 37 percent, roughly one percentage point more than they won five years ago. The center-left Labour Party, led by Ed Miliband, won roughly 30.5 percent, up about a point and a half. Yet Labour’s result was disastrous, in part because it was wiped out in Scotland by the separatist Scottish National Party.

That the two big parties could not even manage 70 percent of the vote between them is one sign of Britain’s political distemper. Another is the electoral revolution in Scotland.

Labour’s roots run deep north of the River Tweed. Scotland was always its bastion. Not this time. By giving the SNP all but three of Scotland’s 59 seats — Labour held 41 of them before the election — its voters signaled not only their frustration that Miliband’s party had taken them for granted over many years, but also that they were fed up with London politicians altogether.

Cameron profited twice over from the nationalist surge. Even on a better day, Labour could not have assembled a majority in Parliament without its Scottish base. And at the close of the campaign, Cameron almost certainly picked up votes in England by warning that Labour could only form a governing majority if it were willing to put the country in hock to separatists. Cameron presented himself as the man who would never pay a ransom and was thus the only choice for English voters who cared about political stability.

But the price of this gambit could be high. The Conservative majority is almost entirely an English majority. Cameron’s approach stoked English nationalism and anti-Scottish feeling, which can only aggravate Scottish resentment. Containing British disintegration will be Cameron’s biggest second-term headache.

His genius for cool political calculation was on display in another respect: In embracing the once center-left Liberal Democrats as coalition allies in his first term, he crushed them. Many on the right-wing of Cameron’s party disliked governing with the Lib Dems. But Cameron understood that allying with Lib Dem leader Nick Clegg would allow him to live up to his promise to create a more moderate brand of Conservatism — and would ultimately discredit Clegg’s party with its own voters.

During Prime Minister Tony Blair’s time in office, Liberal Democrats were to the left of Blair’s Labour Party. The abrupt transformation of the Lib Dems’ identity as enablers of a center-right government was too much, too fast.

And on Thursday, the party’s vote was cut by two-thirds, from 23 percent in 2010 to just under 8 percent. The Lib Dems went into the election with 57 seats and salvaged only eight of them. The Conservatives won more than two dozen of the lost Lib Dem seats, providing Cameron with his new majority. It was a two-step: Weakened by the loss of voters on their party’s left end, the Lib Dems were easy pickings for Cameron, and his party apparatus ruthlessly targeted his one-time allies.

In a lesson for American conservatives, Cameron went out of his way during the campaign to reassure economically hard-pressed voters with promises that he reiterated in his victory speech Friday, including, “3 million apprenticeships,” and “more help with child care.” Cameron was the candidate of a kinder, gentler austerity. By making enough concessions to Miliband’s argument that the working class was hurting, Cameron could focus the country’s attention on good economic news and the SNP threat.

But now that he has a parliamentary majority, Cameron will be challenged inside his party to move away from his signature moderation. Harder-line conservatives will point to Thursday’s thunder from the right-wing United Kingdom Independence Party. UKIP won just one seat, but became the country’s third largest party in popular votes, quadrupling its share to nearly 13 percent. On immigration and Britain’s future with the European Union, Cameron will have limited maneuvering room.

David Cameron has proven himself an electoral wizard. Now he’ll have to reveal a good deal more about what’s behind the curtain.

E.J. Dionne’s email address is ejdionne@washpost.com. Twitter: @EJDionne.

Photo: Number 10 (Official Flickr Account of the Prime Minister’s Office)