Far-Right Infiltration Of The Military Threatens American Society And Values

In April, when Jack Teixeira, a 21-year-old Massachusetts Air National Guardsman with a top-secret clearance, was arrested for posting a trove of classified documents about the Russia-Ukraine war online, the question most often asked was: How did such a young, inexperienced, low-level technician have access to such sensitive material? What I wanted to know was: How did he ever get accepted into the Air Force in the first place?

Teixeira seems to have leaked that secret information for online bragging rights rather than ideological reasons, so his transgression probably wouldn’t have fallen under the military’s newly reinforced regulations on extremist activities. After he was indicted, however, perturbing details about his behavior emerged, including his online searches for violent extremist events, an outsized interest in guns, and social media posts that an FBI affidavit called “troubling” and I’d call creepy.

Ideological zealotry is disruptive wherever it takes root, even if it never erupts into violence, but it’s particularly chilling inside the military. After all, servicemembers have access to weapons and the training to use them. Even more significant, a kind of quid pro quo exists between the military and civilians. Trust is paramount within the military and every service member is supposed to abide by a code of ethics, as well as by the Constitution, to which all of them swear an oath.

In theory, a democratic civil society invests its military with the authority to use force in its name in exchange for the principled conduct of its members. Military service is supposed to be a higher calling and soldiers better (or at least better behaving) people. So when active-duty personnel or veterans use violence against the system they’re sworn to protect, the sting of betrayal is especially sharp.

Whoops!

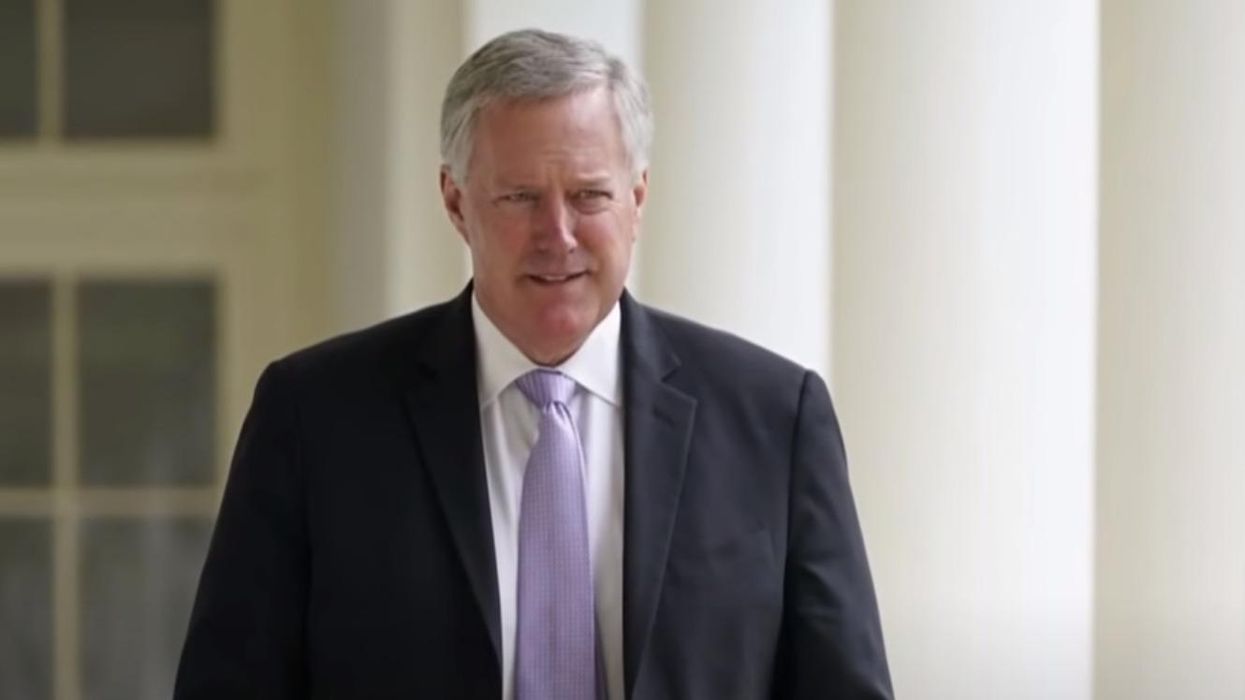

In a photo of Teixeira in a neat dress uniform that accompanied media reports, he’s a bright-eyed kid with stick-out ears and a sweet half-smile. He looks young and promising, the kind of guy people offer thanks to when they see him in uniform at an airport. In reality, however, everything else about him was a red flag.

The Washington Post found videos and chat logs that suggested he was getting ready for a race war. Former classmates told CNN that he had been obsessed with guns and war. He was suspended from high school for comments he made about Molotov cocktails. His first application for a gun license was denied, but he kept trying and was eventually approved, over time amassing a trove of handguns, rifles, shotguns, high-capacity weapons, and a gas mask, which he kept in a gun locker about two feet from his bed.

Granted, some of this activity didn’t begin until he enlisted in 2019 and no one’s advocating that military recruiters make bedroom checks. Still, recruits are supposed to go through a careful vetting process. Family, friends, teachers, and classmates may be interviewed to assess a recruit’s character and fitness. Such background checks are designed to detect things like racist tattoos, drug use, gang affiliation, or arrest records, but are inevitably limited in what they can discover about young people without much life experience, including the teenage gamers the Air Force woos for their up-to-the-minute technical skills who may not prove to be the most level-headed crew — people, in fact, like Jack Teixeira.

In his case in particular, the vetting of service members for handling the top-secret or sensitive-compartmentalized-information security clearances he received in 2022 is supposed to be particularly thorough. I was first faced with this reality when a government agent showed up at my door, flashed a badge, and asked me about a neighbor applying for a clearance. He inquired all too casually about whether I had noticed anything telling, like lots of liquor bottles in his trash. (That left me wondering how many people check their neighbor’s garbage.)

Teixeira’s posts of classified material taken from the computers of the intelligence unit at the Cape Cod air base where he was stationed first appeared on Thug Shaker Central, a small, obscure chat group which appealed largely to teenage boys through adolescent humor, a fetishistic love of guns, and extreme bigotry. It was hosted on the gamer-centric platform Discord. At first, he posted transcribed documents, then began photographing hundreds more in his parents’ kitchen and started uploading copies of them filled with secret materials on the U.S., its allies, and its enemies. Someone at Thug Shaker began sharing those posts more widely and they made their way to Russian Telegram channels, Twitter, and beyond — and Teixeira was in big trouble.

Since he seems to have made no effort to hide who he was, no one could call him the world’s smartest criminal. He made it all too easy for the FBI to track him down. By then, Air Force officials had already admonished him for making suspicious searches of classified intelligence networks, but allowed him to stay in his job. That’s where the Justice Department charged him with the retention and transmission of classified information under the Espionage Act of 1917, which had already caught in its maw journalists, dissidents, whistleblowers (including Daniel Ellsberg, who, to the end of his life, wanted to challenge the act in court on First Amendment grounds), and most recently, another hoarder of classified documents, former President Donald Trump.

In June, Teixeira pleaded not guilty on six counts, each carrying a maximum penalty of 10 years in prison and a fine of up to $250,000. Probably just as happy to let the civilians handle it, the Air Force removed the intelligence division from his unit, but it hasn’t yet brought charges against him.

Meanwhile, Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin ordered a policy and procedure review to assess how bad Pentagon security really was. The results, made public on July 5th, gave the military a passing grade but, with a firm grasp of the obvious, recommended more careful monitoring of the online activities of personnel with security clearances.

Small Numbers, Outsized Impact

Rhetoric and regulations addressing extremism in the military date back to at least 1969 and have been tinkered with since, usually in response to hard-to-ignore events like the murder of 13 people at Fort Hood by Army psychiatrist Nidal Hasan in 2009. In reaction to the material Chelsea Manning (who was anything but an extremist) leaked to WikiLeaks to reveal human-rights abuses connected to the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, the Department of Defense created a counter-insider threat program around 2014. Six years later, the Army revised its policies for the first time to face the potential role of social media in extremist activities.

Tracking and reporting on extremism in the military has not been without controversy, which tended to be of the let’s-not-air-our-dirty-laundry-in-public variety. In 1986 when, for instance, the Southern Poverty Law Center informed the Department of Defense (DoD) that active-duty Marines were participating in the Ku Klux Klan, the Pentagon responded that the “DoD does not prohibit personnel from joining such organizations as the Ku Klux Klan.” (It still doesn’t name or ban specific organizations in its regulations.) And when, in 2009, a Department of Homeland Security assessment warned of right-wing extremists recruiting veterans, conservative politicians and veterans groups killed the report which, they claimed, was insulting to veterans.

Then came the invasion of the Capitol on January 6, 2021. A striking number of participants proved to have military connections or histories — 13.4% to 17.5% of those charged, depending on who’s counting — and the Pentagon could no longer ignore the problem. Defense Secretary Austin ordered an unprecedented, day-long stand-down to educate all military personnel on extremist activity and then created the Countering Extremist Activity Working Group, or CEAWG, to come up with a plan for dealing with that anything-but-new reality.

It’s not possible to pin down the true scope of the phenomenon, but the Center for Strategic and International Studies found active-duty and reserve personnel were linked to seven of the 110 terrorist attacks and plots the FBI investigated in 2020. That same year, the New York Times estimated that active-duty military personnel and veterans accounted for at least 25% of antigovernment militias. In 2022, the Anti-Defamation League identified 117 active-duty service personnel and 11 reservists on a leaked membership list from the Oath Keepers, the far-right antigovernment militia prominently involved in January 6th events. CEAWG, on the other hand, claimed that, in 2021, there were fewer than 100 substantiated cases of military personnel involved in officially prohibited extremist activity in the past year.

While such reckonings suggest that just a small number of servicemembers are actively involved in extremist violence, even a relative few should be concerning for obvious reasons.

Report, Revise, Reconsider

Opportunities to identify and prevent extremism arise at three junctures: during recruitment, throughout the active-duty years, and in the discharge process when those transitioning back to civilian life may be especially susceptible to promises of camaraderie and ready action from extremist groups. As 2021 ended, the Pentagon’s working group reported that it had addressed such vulnerabilities by standardizing questionnaires, clarifying definitions, and — that old bureaucratic fallback — commissioning a new study.

The revised rules included a long list of banned “extremist activities” and a long definition of what constitutes “active participation.” In addition to the obvious — violence, plans to overthrow the government, and the leaking of sensitive information — prohibited acts include liking, sharing, or retweeting online content that supports extremist activities or encouraging DoD personnel to disobey lawful orders with the intention of disrupting military activities.

Active participation includes organizing, leading, or simply attending a meeting of an extremist group and distributing its literature on or off base. Commanders may declare places off-limits where “counseling, encouraging, or inciting Service members to refuse to perform duty or to desert” occurs. That also sounds like it could apply to gatherings of antiwar groups like Veterans for Peace, where supporting war resisters is part of their mission. And therein lies the rub.

As in the past, the updates focus on activity, rather than speech, which is a good thing, but figuring out how to suppress extremism without turning into the thought police is challenging, particularly in light of the prominence of social media and the impossibility of monitoring everyone’s online activity. The result: regulations that are both too vague and too restrictive and a recipe for implementing the rules unfairly.

In military culture, reporting is often equated with snitching and retaliation is common. Since it’s not practicable to draw bright lines between what’s allowed and what isn’t, that determination rests ultimately (and sometimes ominously) with commanders. The regulations urge them to balance First Amendment rights with “good order and discipline and national security.” In reality, however, such decisions too often fall prey to bias, distrust, self-interest, racial disparities, and a history of bad faith.

Then there’s the issue of paying for the extra work the rules require. The only relevant funding seems to be a puny $13.5 million for the insider-threat program. Meanwhile, the Pentagon budget that recently exited the Republican-controlled House Appropriations Committee makes it a “conservative priority” to defund the position of Deputy Inspector General for Diversity and Inclusion and Extremism in the Military. So anti-extremism may prove but one more victim of anti-diversity and, even without that, if money is a measure of commitment, the military’s commitment to fighting extremism is looking lukewarm at best.

Consistently Inconsistent

Recently, the Center for New American Security, a D.C.-based think tank, damned the military’s efforts to address domestic violent extremism historically as being all too often “reactionary, sporadic, and inconsistent” when it comes to recognizing the problem to be solved, or even admitting there is one. Though harsh, it’s not an unfair assessment.

The National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START), a Department of Homeland Security research center at the University of Maryland, analyzed an extensive database of extremist activity in the U.S. called PIRUS and found that 628 Americans with military backgrounds were involved in such criminal activity from 1990 to March 2023. Almost all of them were male veterans, with Marines showing up in disproportionately large numbers (as they did among the January 6th arrestees). A slight majority of the cases considered involved violence and a large majority involved white supremacist militias. And here’s an intriguing fact that probably won’t surprise anyone who’s followed the U.S. military’s dismal war record in this century: extremists with a military background were less successful in carrying out violent attacks than those without it.

Indeed, the extremist threat appears to be growing. A chart in a research brief looking at PIRUS data shows little blips for extremist cases in most years until the past six, including not only the (hopefully) unrepeatable 2021, but the years on either side of it.

Activities that rise to the level of criminal conduct, however, tell only part of the story.

The RAND Corporation interviewed a large, demographically representative sample of veterans — mostly older, white, middle-class men who joined the military before 9/11 — to assess sympathy for extremist organizations and ideas. The researchers found no evidence that veterans support violent extremist groups or their ideologies more than the rest of the American public does.

If you find that reassuring, however, think again. After all, according to the 2022 Yahoo! News/YouGov poll Rand used for comparison, a little more than a third of the U.S. population agrees with the Great Replacement Theory that “[a] group of people in this country are trying to replace native-born Americans with immigrants and people of color who share their political views.” Am I supposed to be comforted because only about five percent fewer veterans think that?

Then there’s the finding that almost 18 percent of the veterans surveyed who agree with one of four cited extremist ideologies also support violence as a means of political change. That finding is scary, too, because extremist groups can take advantage of such veterans’ support for political violence to recruit them for their often all-too-violent purposes.

All of this leaves me very uneasy, both about what is being done and what should or even could be done. I worry about how much more extreme and violent this country has become in this century of failed wars. And I worry about anti-extremism policies sliding into prosecuting — and persecuting — people for disfavored beliefs, while immediate danger glides in from some unexpected source — like a 21-year-old techie, who, for reasons no one anticipated, pulled off one hell of a breach of national security right under the military’s nose.

Reprinted with permission from Tom Dispatch.