Biden's New 'Harm Reduction' Policy Could Actually Stem Opioid Epidemic

A deadly plague continues to rage across America, and neither vaccines nor face masks nor herd immunity can stop it. The epidemic of drug overdose deaths has taken more lives than COVID-19 and is more intractable. But the Biden administration is showing a welcome openness to a new strategy.

That approach is known broadly as "harm reduction." The idea is that drug abuse should be regarded as a public health problem, not a crime or a sin. Prohibiting and punishing drug use doesn't work. A better option is helping illicit users modify their behavior to reduce their risks.

"I believe this administration is the first to use the term 'harm reduction' in its drug strategy," says Maritza Perez, director of the office of national affairs for the Drug Policy Alliance.

The risks of opioid use in particular are grave and growing. In 2019, the number of drug overdose deaths was 70,630, the highest ever, and most involved opioids. But in 2020, the total was 93,331, an increase of 32 percent. Since 1999, more than 900,000 Americans have died of drug overdoses.

The epidemic has its roots in the 1990s, when drug companies brought out new opioids such as OxyContin, which were marketed as safe for treating chronic pain. But many patients became addicted, and some died of overdoses.

You might think that the federal crackdown on pain prescriptions and the successful lawsuits against pharmaceutical companies would make a big difference, and you would be right: The number of fatalities involving nonprescription opioids has soared.

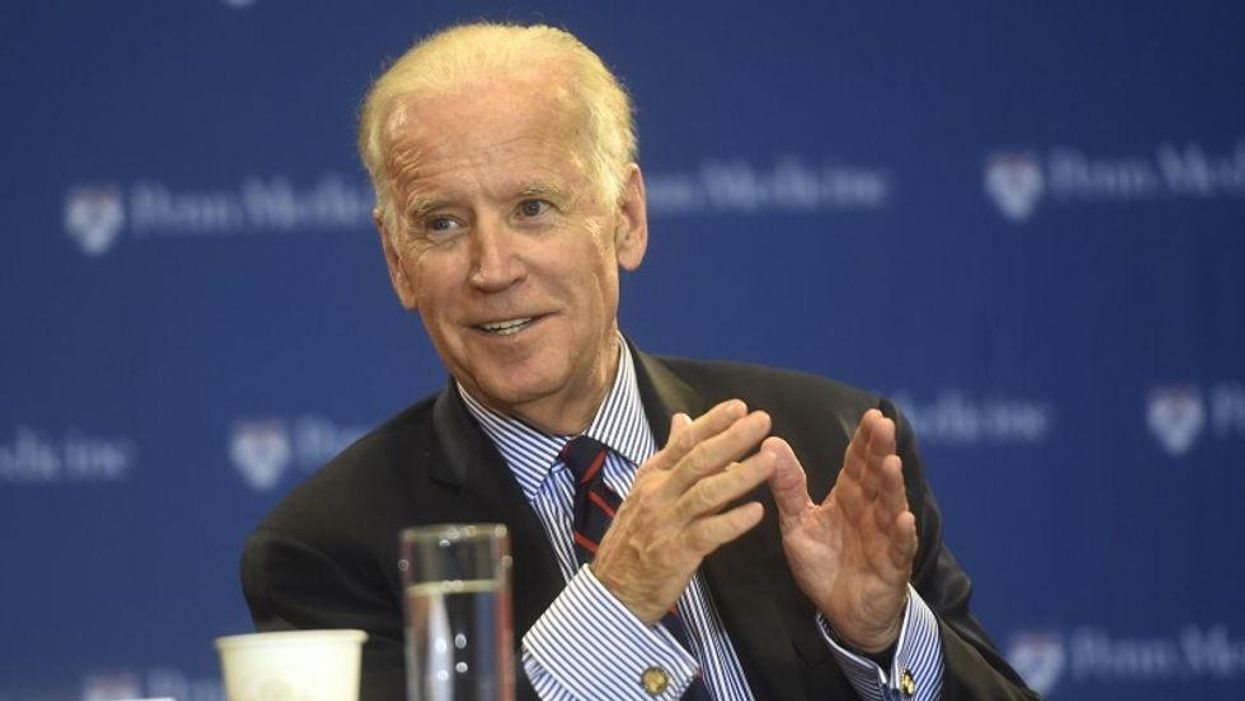

For the past half-century, presidents of both parties have seen drug abuse as a job for police and prosecutors, relying on harsh punishment to deter buyers and sellers. But mass incarceration failed — and President Joe Biden, who helped bring it about as a U.S. senator, now recognizes it was "a big mistake."

Today, he's embracing something different: trying to keep drug users alive while facilitating their access to ways of overcoming addiction and avoiding death. The COVID-19 relief act enacted this year includes $30 million for programs aimed at harm reduction.

Among these are syringe services, which let injecting drug users get free, sterile needles without fear of arrest. These are a time-tested method of curbing lethal diseases, including HIV and hepatitis C, but they have long been barred from federal funding. President Barack Obama got the ban lifted, but when Republicans regained control of Congress in 2011, they restored it.

Even former Vice President Mike Pence, however, was willing to allow syringe services when things got dire enough. As governor of Indiana in 2015, he approved a program in one county to combat a severe outbreak of HIV. "I will tell you that I do not support needle exchange as anti-drug policy," he said then. "But this is a public health emergency." The program was a phenomenal success.

The White House has issued a long statement of its drug policy priorities, with an eye to reducing fatal overdoses. It promises to improve access to drugs used to treat and overcome opioid dependence. It endorses efforts to promote the use of naloxone, which can reverse overdoses, and test strips to detect fentanyl, a highly potent opioid that suppliers often mix into heroin and cocaine — with sometimes tragic results.

The point is not only to save drug users from sudden death but also to give them a path away from addiction. Harm-reduction organizations, the White House statement says, "can build trust over time with patients and are in a unique position to encourage (drug users) to request treatment, recovery services and health care." This year's expansion of the Affordable Care Act has also made it possible for more people to get mental health and substance abuse treatment.

But the addiction to law enforcement is hard to break. Biden has proposed to make permanent the Trump administration's policy of classifying all fentanyl-related substances as Schedule I drugs, exposing users to stiff criminal penalties.

That's the opposite of harm reduction — adding the hazards of imprisonment to the risk of overdose. Not to mention that, as we've learned from decades of trying to eradicate cocaine, heroin and methamphetamines, locking up people for using drugs doesn't keep people from using drugs.

Biden has taken a big step toward a better future. But he still has one foot stuck in the past.

Follow Steve Chapman on Twitter @SteveChapman13 or at https://www.facebook.com/stevechapman13. To find out more about Steve Chapman and read features by other Creators Syndicate writers and cartoonists, visit the Creators Syndicate website at www.creators.com.