Texas Trumpers' Assault On Biden Bus Previewed Capitol Riot

This article was first published by The Texas Tribune, a nonprofit, nonpartisan media organization that informs Texans — and engages with them — about public policy, politics, government and statewide issues.

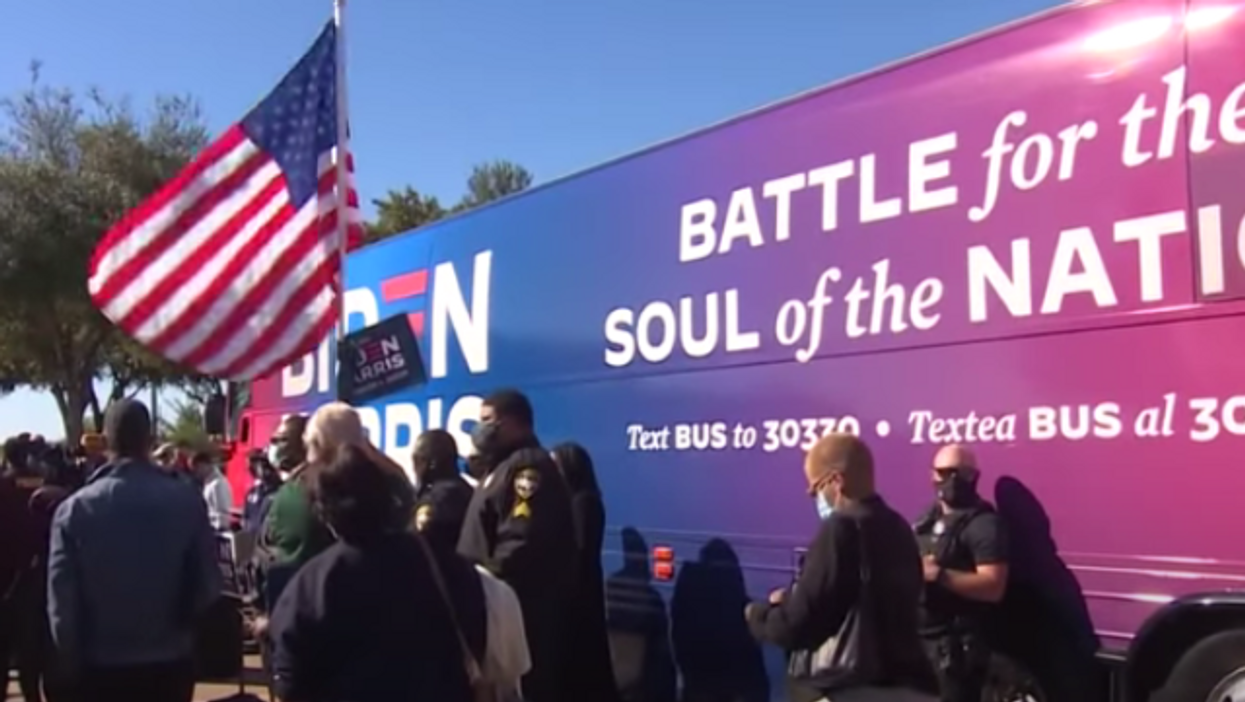

Nine weeks before invaders violently took siege on the U.S. Capitol, President Donald Trump's zealous supporters swarmed a Joe Biden presidential campaign bus driving through Central Texas, waving "Make America Great Again" flags, shouting profanities and ultimately frightening those on board enough that Democrats canceled multiple campaign events that evening.

Former Texas state Sen. Wendy Davis, who was on the bus, said that law enforcement authorities didn't take that incident seriously enough and now sees it is an example of how Trump supporters have become dangerously emboldened to act lawlessly, fueled by some Republicans who either tacitly or explicitly encouraged the sort of violence that culminated with last week's attack.

"This is a symptom of a broader problem that is not going away. This truly is the birth of a domestic terrorist unit. And I think that the FBI and local law enforcement need to see it this way," said Davis, who spoke publicly about the October incident for the first time on Monday to The Texas Tribune. "It's no surprise that we see things like Wednesday of last week in our nation's Capitol, when people who are behaving aggressively like that are rewarded and praised by their quote-unquote leader for that kind of behavior."

Davis described a sense of déjà vu as she watched on TV last week the people storming the Capitol building who displayed the same aggression, anger and discontent she witnessed just a few months ago when she and three others on the campaign bus were surrounded by a caravan of Trump supporters. She noted that the violence at the Capitol which resulted in five deaths was much more severe.

The bus incident, which resulted in a minor collision between a Biden volunteer driving behind the bus and a Trump supporter, was caught on video and made national headlines just days before the November election. It also garnered praise from Republican leaders.

A day after the incident, Trump tweeted a video of the Trump supporters following the Biden bus saying, "I LOVE TEXAS!" and falsely claimed his supporters were "protecting" the bus.

Florida GOP Sen. Marco Rubio also heaped on praise at a Trump rally in Miami a few days after the incident.

"Did you see it? All the cars on the road, we love what they did," Rubio told Trump supporters.

Davis' campaign had refused to comment at the time as she wrapped up her campaign against U.S. Rep. Chip Roy, which she lost. She said she didn't want to empower the Trump supporters further. Now, she regrets not speaking out, as she views the experience in October as a warning sign.

"I've been in public politics for a long time. This isn't how people who have been on the other side have conducted themselves in the past," she said. "It's risen to a level that is emboldened and embraced, unfortunately, by elected officials, and it's going to continue to rise to these dangerous fever pitches if we don't do something about it."

Davis was interviewed by the FBI a few days after the October incident, she said.

At the time, she said it seems like the federal authorities — who were especially interested in the people involved in the car collision —took the issue seriously, but she has not heard from them since then. She said she was not contacted by any other local law enforcement about the incident. A law enforcement official confirmed the investigation is ongoing.

Davis said the Biden campaign had already decided not to broadcast where the campaign bus was headed on Oct. 30 after social media posts showed Trump supporters were looking to target the campaign as it made its way through Central Texas. She said a Trump supporter found them at the voting location at the AT&T Center in San Antonio and alerted other supporters on social media.

The supporters, driving mostly pickup trucks donning Trump flags, quickly found the bus as it was leaving the city. Davis said the San Antonio police responded to a request for assistance, pushing the trucks back. But once they left San Antonio, the caravan surrounded the bus again. Davis said they called 911 again in San Marcos but they could not get an officer to respond.

"They just kept saying, 'Where are you now? Where are you now,'" Davis said. "We kept giving them landmark after landmark, mile marker after mile marker...Never were we able to get anyone to come out. It was unbelievable."

A spokesperson for the city of San Marcos said in October that they had dispatched officers, but they were unable to get to the scene before the bus left their jurisdiction because of traffic caused by an unrelated accident.

Davis said she and one of the two bus drivers on board shifted into "combat mode" when they realized law enforcement wasn't going to respond. All four on the bus were extremely shaken, especially when the volunteer driving the car collided with the Trump supporter. The driver ultimately made a last minute maneuver and quickly exited I-35 at Riverside Drive just before approaching downtown Austin. But the group found them again as they neared the AFL-CIO building downtown, where Austin police were waiting for them. Everyone got off the bus and decided to cancel the rest of the campaign events that night.

"After all was said and done and then the couple of days following that, it was given a pass, like it was shrugged off like it was really no big deal," Davis said.

Davis slammed Texas Republican leaders, including Gov. Greg Abbott, Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick and Attorney General Ken Paxton, for encouraging a climate where people feel emboldened to harass others and break the law.

Abbott issued a short statement last Wednesday that the "violence and mayhem must stop." Asked on Wednesday if he thought Trump contributed to the attack on the Capitol, he said "the people responsible for that violence are the people who did it, and they're the ones who should be punished for it." Patrick did not respond to a request for comment.

Paxton led the charge to overturn election results in four battleground states, filing a lawsuit based on baseless conspiracy theories of widespread voter fraud in the November election. He also attended a pro-Trump rally Wednesday in Washington D.C., encouraging people to continue to fight. He perpetuated false conspiracy theories in the hours after the insurrection that those who broke into the Capitol were not Trump supporters.

Ian Prior, a political spokesperson for Paxton, said the attorney general condemns all political violence.

"However, citizens should absolutely 'keep fighting' for their rights at the ballot box, in the courts and through their First Amendment right to peacefully protest," Prior said.

Looking back, Davis wonders if she, too, did not take the incident seriously enough because no one was physically injured.

"I question my own growing immunity to the egregiousness of the way people have behaved, spurred on by Donald Trump," she said. "We can't let things like that ever become our new normal. And we've got to be absolutely forceful in pushing back against it when it happens."

Disclosure: AT&T has been a financial supporter of The Texas Tribune, a nonprofit, nonpartisan news organization that is funded in part by donations from members, foundations and corporate sponsors. Financial supporters play no role in the Tribune's journalism. Find a complete list of them here.

This article originally appeared in The Texas Tribune at https://www.texastribune.org/2021/01/11/wendy-davis-us-capitol-riot-texas/.

The Texas Tribune is a member-supported, nonpartisan newsroom informing and engaging Texans on state politics and policy. Learn more at texastribune.org.