Reprinted with permission from DCReport.

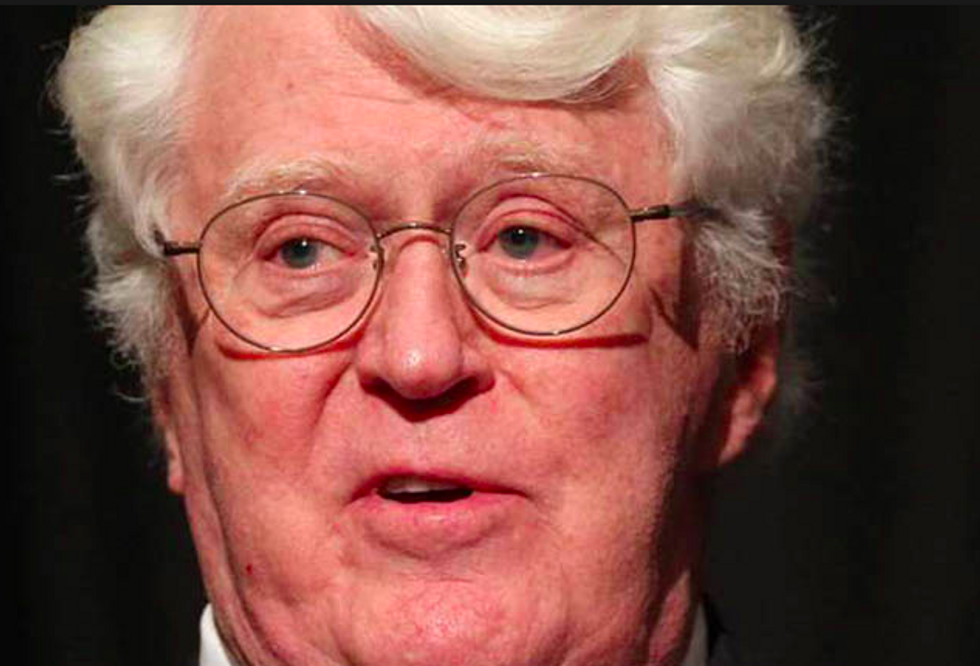

Only one of the billionaire Koch brothers supported Donald Trump’s 2016 campaign: William Ingraham Koch. Bill Koch even raised money for Trump, his nearby neighbor in Palm Beach, Fla.

That same year, IRS criminal agents began an investigation after receiving nearly 1,000 pages of documents detailing what were described as multiple tax frauds at Bill Koch’s companies. The documents, which we call the Koch Papers, came from a deeply knowledgeable source: Charles Middleton, who had been one of the companies’ top tax executives.

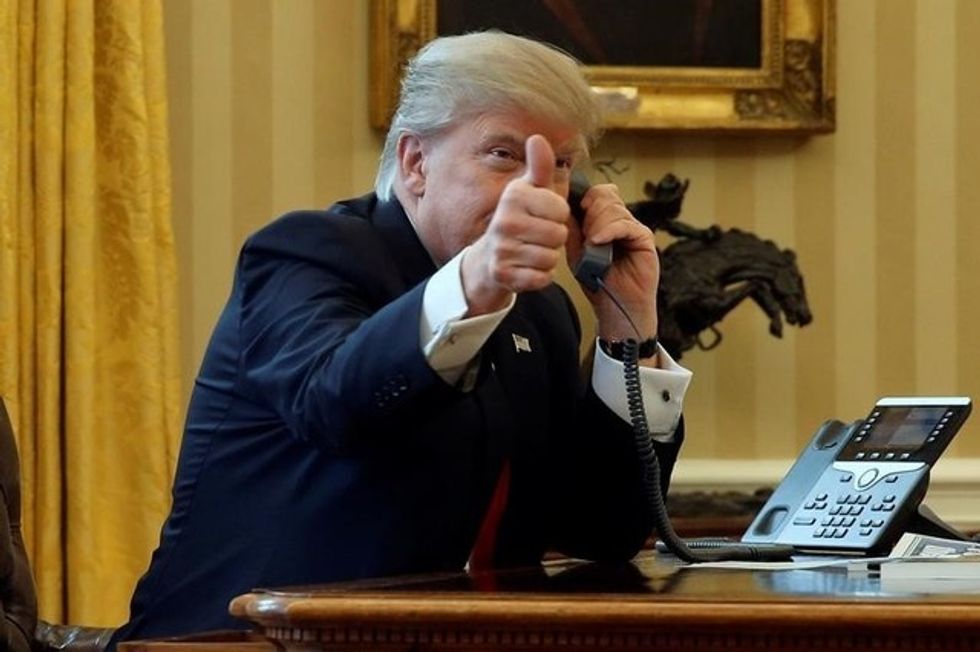

The IRS investigation went cold after Trump assumed office, documents obtained by DCReport show.

Michael Galdys, an IRS criminal investigation agent in West Palm Beach, gave no explanation as to why he was no longer pursuing the case when he sent a June 13, 2017 email to one of Middleton’s lawyers, William Cohan, in Rancho Santa Fe, Calif.

Cohan, and Middleton’s Seattle lawyer, John Colvin, both say the IRS and Justice Department stopped acknowledging their calls, emails and letters after Trump became president.

Koch’s company, in a written statement, said Bill Koch “has not approached President Trump to discuss any significant Company business issues, tax-related or otherwise.” The company also said it discharged Middleton “for cause” and noted that the IRS closed an audit of the company’s 2011 and 2012 tax returns without making any changes.

The Koch Papers detail what Middleton and his lawyers say were multiple tax dodges over many years. The biggest involves profits from selling petroleum coke, a residue from oil refining that is among the dirtiest of all carbon fuels.

Two of Bill Koch’s better known and much richer brothers, Charles and David, are also heavily invested in carbon industries and in promoting their libertarian political philosophy. In 1983, Bill, who is David’s twin, sold his shares in the family business and set up his own operations under the Oxbow moniker. Charles and David have no involvement with Bill Koch’s company.

While his brothers are worth more than $50 billion each, according to Bloomberg News, Bill Koch, 79, is worth about $4.1 billion. He holds a Doctor of Science and two other chemical engineering degrees from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

The Koch Papers are remarkably clear and complete, raising questions about why the IRS would choose not to pursue an inquiry. The head of the Justice Department’s tax division, which decides which IRS cases to pursue criminally, was notified of the case during the last days of the Obama Administration, the Koch Papers show.

The sham corporate tax shelters I’ve exposed over the decades were subtle, complex contracts, the legal equivalent of Rube Goldberg contraptions built on highly technical, and twisted, interpretations of tax law.

The Koch Papers, by contrast, reveal simple techniques. But recognizing those techniques would require seeing documents that were withheld from IRS auditors, Middleton wrote.

William Koch now owes our government hundreds of millions in taxes, penalties and interest, my analysis of the Koch Papers and other documents indicates, but he and his company would pay nothing if the investigation remains closed.

Federal law allows whistleblowers to collect up to 30 percent of any taxes, penalties and interest the IRS recovers as a result of the whistleblower complaint. However, Middleton cannot collect any reward under terms of his separation agreement with Koch’s company, according to Cohan, Middleton’s main lawyer.

Cohan said that while his client may be contractually blocked from keeping any IRS reward, he and Colvin, Middleton’s other lawyer, may be able to collect. However, both Colvin and Cohan said they have no expectation that the Trump administration will pursue their client’s whistleblower complaints. They said their interest was in pushing for fair enforcement of tax laws.

Investigation Halted

Cohan said he believes “Trump made a call and that was all it took to stop the investigation.” A White House spokesman, in an email, issued a non-responsive comment that he declared was “off the record.” (Journalists, not sources, decide what is off the record.) A second request drew no reply from the White House.

Any Trump involvement would also be appropriate for Congress to investigate, both as a matter of potential criminal conduct and as a potential article of impeachment. Trump vowed to voters that he would “drain the swamp” and to “put America first” under policies that in every instance “will be made to benefit American workers and American families.”

But even if Trump played no role, Congress can obtain the tax documents, question Koch and his senior staff, as well as IRS auditors and those involved in the seemingly aborted criminal inquiry.

Bill Koch has a well-established reputation as a serious businessman who intensely analyzes deals and watches his money closely. The Koch Papers show he was actively engaged in the tax-avoidance efforts. Middleton’s whistleblower complaints and letters by his lawyers assert that he crossed line from lawful tax minimization into tax fraud.

The biggest plan described in the Koch Papers was conceptually simple. It involved various Koch carbon companies under the umbrella of parent company Oxbow Carbon LLC that all shared the name Oxbow. For simplicity, we will refer to them as Oxbow America and Oxbow Bahamas.

Oxbow America bought petroleum coke, also known as petcoke. Various grades are mixed and then sold to different buyers. Low-quality petcoke is burned as fuel in Japan and South Korea, while the best quality helps anodize aluminum and other metals.

The petcoke profits were exceptional, in part because Oxbow America, through a real estate deal, blocked competitors at the Port of Long Beach in California.

That deal gave Oxbow America exclusive access to sell Southern California petcoke to Asian markets. Because of the costs of transporting petcoke by rail or truck, the Long Beach deal made profits per ton of petcoke there exceptionally profitable, company financial calculations show.

The Oxbow companies were organized so that tax bills flowed through to Bill Koch.

With profits of more than $100 million annually, federal taxes of $40 million to $50 million were owed each year, the internal documents show, through 2017. (The Trump/GOP tax law discounts subsequent tax bills by about 5%.)

To escape these taxes, Oxbow America created a shell company in Switzerland, which in turn operated in the tax-free Bahamas. Profits were then attributed to Oxbow Bahamas, wiping out all income taxes.

This brings up two important areas of tax law. When it comes to taxes, substance trumps form. Tax benefits are allowed only when there is a legitimate business purpose to transactions. Business actions designed solely to evade taxes are shams. When discovered during audits these shams are disregarded and taxes are assessed.

In the Koch Papers, reports by consultants, executives and tax advisers suggest that escaping taxes was the sole motivation for creating Oxbow Bahamas. Colvin, the lawyer for Koch’s then top tax executive, wrote to the government that the documents show “the only reason for Oxbow’s creation of the Bahamas office was to avoid U.S. tax.”

No other benefit, such as increased efficiency, was even considered, lawyer Colvin wrote. The Koch Papers show no indication of a business purpose, only escaping taxes.

Significantly, however, the Bahamas deal was evaluated on the basis of whether it would be detected in an IRS audit and what that might cost. Bill Koch’s company’s home office in West Palm Beach, Fla., performed calculations to determine that potential expense.

Playing ‘Audit Roulette’

The report estimated “the net present value” of shifting profits to Oxbow Bahamas using “several alternative assumptions on the likelihood of being audited,” Colvin wrote.

“This document is literally a ‘tax audit roulette’ calculation,” Colvin wrote, referring to the practice of tax cheating based on the risk of getting caught, which is small overall and especially small when complex international transactions are involved. The IRS told Congress several years ago that it lacked the expertise and time to unravel many tax dodges, a disclosure that surely emboldened any individuals, business owners and executives already inclined to cheat.

A report for Oxbow America by outside consultant Robert VanKleek cited estimated tax savings of $21 million annually unless challenged by the IRS. But, Colvin wrote, “it was actually between $40M and $50M per year.”

The second key area of law is Section 864 of the tax code. It says that “the term ‘produced’ includes created, fabricated, manufactured, extracted, processed, cured, or aged”—all terms that describe the petcoke produced by Oxbow America’s operations. That section also provides that income from “producing” in the United States is “effectively connected” to America and will be taxed by our Congress.

The number of employees and locations of operations tell the story of where petcoke was produced and profits earned.

Oxbow America employs about 300 people, including a half dozen sales agents making more than $1 million annually selling millions of tons of petcoke, the Koch Papers show.

Oxbow Bahamas had just three employees, later increased to five. Not a single pound of petcoke was produced there. The Bahamas boss was a $115,000-a-year executive so junior that internal company reports state that he was not qualified even to run that small operation, much less the global petcoke enterprise controlled by Bill Koch.

Oxbow America sales agents were told that revenue from the deals they made was to be attributed to Oxbow Bahamas once it was set up even though it did not have enough staff just to track and process invoices.

The transferred contracts were “deep in the money,” meaning they had large built-in profits that would be harvested as soon as each contract was completed, the Koch Papers reveal. Middleton, Koch’s former tax expert, wrote in October 2016 to Teresa Homola of the IRS Whistleblower office that “Oxbow misrepresented the nature of its business to the IRS. The analysis delivered to the IRS concluded that Oxbow’s U.S. supply contracts had no value.”

An email by Bill Koch, written as delays in setting up the Bahamas operation mounted, complains that “I am being flooded with emails and complaints that the LOB (line of business) managers are getting conflicting instructions and information on how to do deals properly…”

Middleton wrote that “It is obvious from these emails that the Bahamas structure was motivated by tax. The business guys were not driving it. Since it wasn’t driven by business considerations, the business guys wanted clear instructions on how to achieve the tax goals.”

A consultant’s report stated that another of Oxbow’s staff tax lawyers “does NOT believe that Oxbow is acting correctly with regard to the tax implications/exposures concerning [Oxbow Bahamas]. His philosophy seems to be ‘we can beat them in court….’” A 2009 email to Koch and two senior executives warned that the Bahamas project was not properly structured to comply with tax law. “Oxbow’s exposure could be horrific – penalties are huge,” the email warned.

Some deals “have not been structured correctly,” Koch was told in writing.

“I wonder if the Bahamas operation has been carefully thought out tax-wise,” the same writer advised Koch.

The email also said the person Koch sent to the Bahamas was much too junior to be in charge.

In April 2010, Oxbow America’s contracts were transferred to Oxbow Bahamas. The Bahamas firm paid nothing for these contracts even though they were “deep in the money.”

Shifting money this way is known as “assignment of income.” Under a 1930 Supreme Court ruling, neither people nor companies can assign their income to another party to reduce or escape taxes. Numerous court rulings since have strengthened this doctrine.

The transfer of these valuable contracts was also affected by a subtle change in new contracts with petcoke buyers.

Previous contracts transferred title at the edge of the railroad line delivering the petcoke or when it was loaded onto a ship docked at Long Beach. The new language said the transfer occurs “on the high seas in international waters.”

Lawyer Colvin said that the transfer at sea language was adopted because Oxbow executives “believed that transferring title outside the United States was important for the tax treatment being sought. However, the actual shipping practices did not change, and most of the purchasers continued to arrange for their own shipping and insurance.”

In an interview, Colvin confirmed that he regards the transfer at-sea language as a sham that the IRS should disregard.

The report by consultant VanKleek warned of other tax problems in Belgium, India, and the Netherlands, noting that the “Rotterdam tax people are very aware of DUTCH law and fear that when a contract transfer is made Oxbow may be exposed to significant tax exposure in Holland.”

The report cited “a lack of transfer pricing policy” with major potential tax costs saying in all caps “THIS IS VERY IMPORTANT.”

Referring to Oxbow Bahamas, the report spoke of “bad tax advice” and noted that Bill Koch “has the responsibility to make sure” it is done properly.

Emails and other documents show that Bill Koch knew that the Bahamas tax avoidance depended on precise execution if it was to have any chance of being upheld by IRS auditors.

An internal analysis estimated that each business day’s delay in attributing profits to the Bahamas cost about $85,000, which totals $21 million for the year. After the Bahamas plan was put into effect, the Koch Papers show, that estimate proved to be less than half the actual taxes avoided.

“I am very worried that it is not being done properly,” Bill Koch wrote in an email, adding in capital letters, “HIRE SOMEONE WHO UNDERSTANDS THESE TAX ISSUES.”

Koch’s company soon hired Charles Middleton, who came with deep experience and knowledge of international tax issues and an LLM, the highest degree in tax law, from New York University. As senior vice president for tax, Middleton was Koch’s top tax lawyer. He signed company tax returns.

Middleton told the IRS he relied on what others told him in signing the 2010 tax returns and related documents for Koch’s carbon companies. Middleton wrote that he subsequently concluded that the 2010 tax return was fraudulent.

No Time Limit on Tax Fraud

If the Trump administration pursues the Koch tax behavior and finds fraud, it can collect taxes, penalties and interest back to 2010. That is because while there is a basic six-year limit on reaching back to collect unpaid taxes, there is no time limit when tax fraud is involved.

American tax law allows the IRS to reopen any audit where fraud was used to deceive auditors. Tax fraud can be pursued as a civil matter and also prosecuted as a felony, punishable with long prison terms.

Congress has absolute authority to inspect the tax returns under a 1924 anti-corruption law, to compel IRS Special Agent Galdys and others to testify in public hearings and to enact new laws to undo other tax dodges that Middleton uncovered when he was Koch’s top tax executive. Congress can also investigate who issued the orders to stop the IRS’s criminal investigation.