By Anita Kumar and William Douglas, McClatchy Washington Bureau

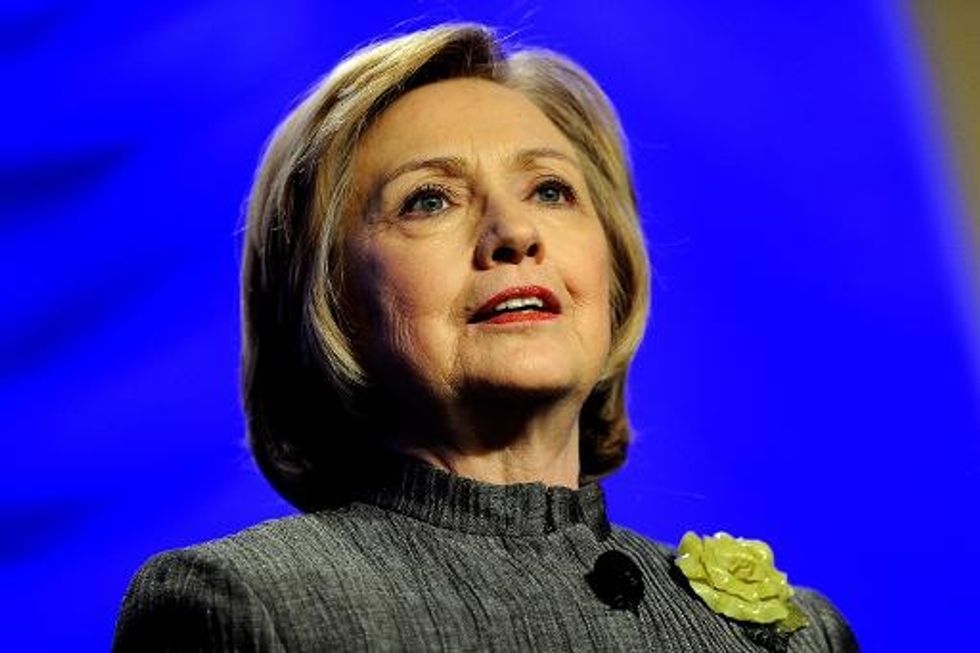

WASHINGTON — Hillary Clinton isn’t running for president yet, but she’s already learning that it’s not easy running away from her former boss, even if he’s unpopular.

After spending a year and a half praising Barack Obama, the former secretary of state is starting to distance herself from the president. In a blunt interview in The Atlantic, Clinton dismissed Obama’s foreign policy as focusing on avoiding mistakes overseas that could lead to military involvement.

“Great nations need organizing principles, and ‘Don’t do stupid stuff’ is not an organizing principle,” Clinton told interviewer Jeffrey Goldberg, referring to a phrase Obama has used to describe his resistance to intervention.

Clinton’s comments are her strongest to date against Obama, who faces a series of global crises while suffering from low approval ratings, especially on foreign policy.

“This is one smart lady. Nothing happens by coincidence,” said Aaron David Miller, a former adviser to Democrats and Republicans at the State Department who now serves as a distinguished scholar at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington. “It’s an attempt to differentiate herself from an unpopular president. This is inevitable. You are going to see more of it.”

But the interview foreshadows a challenge for Clinton if she does run for president in 2016. How does she differentiate herself from a president without appearing to be disloyal, a flip-flopper or an ineffective secretary of state? And how much did she really differ from Obama?

Clinton called Obama on Tuesday, working to assure him that she was not attacking him, his policies or his leadership.

“Secretary Clinton was proud to serve with President Obama, she was proud to be his partner in the project of restoring American leadership and advancing America’s interests and values in a fast-changing world,” said Clinton spokesman Nick Merrill.

Merrill acknowledged that Clinton and Obama have had “honest differences” on some issues, including Syria, but he said some people are hyping those disagreement. “Like any two friends who have to deal with the public eye, she looks forward to hugging it out when they see each other” at an event Wednesday night on Martha’s Vineyard.

Conflicts between top members of an administration are not new, some laid bare in real time, others revealed later as understudies run for election themselves.

Democrat Hubert Humphrey waited until late in the 1968 campaign to break with President Lyndon B. Johnson on Vietnam. He had a surge in the polls just before the election but still lost narrowly to Republican Richard Nixon.

Vice President Al Gore in 2000 had to straddle defending President Bill Clinton over his impeachment and sexual relationship with White House intern Monica Lewinsky while distancing himself from Clinton’s behavior as he was running for president.

Two secretaries of state resigned over disagreements with their presidents. Cyrus Vance resigned in 1980 in protest over Jimmy Carter’s planned military rescue mission to free American hostages from Iran, predicting that it would fail, which it did. William Jennings Bryan resigned in 1915 because he thought President Woodrow Wilson’s policies would lead to war.

In a sign of the challenges, Clinton’s remarks were criticized by the right, which seeks to remind people that she’s closely associated with Obama’s foreign policy, and the left, which fears she will prove too hawkish.

“Let’s be real, she was the Obama foreign policy for four years,” said Kirsten Kukowski, a spokeswoman for the Republican National Committee. “And in year five, it’s ridiculous to ask Americans to believe that the results we’re seeing today aren’t a product of Obama-Hillary diplomacy.”

From the left, Obama’s longtime adviser, David Axelrod responded harshly to Clinton on Twitter. The liberal group MoveOn Political Action said Clinton should think before embracing the same policies that got America into the Iraq War.

But some say that Clinton offers a philosophy on foreign policy that could be appealing to those who think Bush overreached and Obama under-reached.

“The time is better now for Hillary Clinton’s message than 2008,” said David Rothkopf, a visiting scholar at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, a think tank, and CEO and editor of Foreign Policy magazine. “She has a foreign policy approach that is much more likely to be embraced in the general election.”

Her moves suggest she’s assuming she can afford to upset Democratic primary voters while coasting to her party’s nomination, instead positioning herself for the general election.

Indeed, criticizing Obama could anger partisan Democrats and liberals who are traditionally the most vocal and most influential in the primaries. A new McClatchy-Marist Poll this week found that even while a solid majority of voters does not like Obama’s foreign policy, Democrats approve of it by 65 percent to 28 percent, and liberals approve by 68 percent to 28 percent.

However, the Democratic nominee will need to reach out to other voters in the general election. And the McClatchy-Marist Poll found that independents disapprove of Obama’s foreign policy 64 percent to 31 percent, and moderates disapprove 53 percent to 39 percent.

“Clinton may think she can write off the anti-interventionist left — again — and win the White House this time,” liberal writer Joan Walsh wrote at Salon.com. “But she may find out she’s wrong this time, too,” a reference to Clinton’s failed campaign against Obama for the Democratic nomination in 2008.

Obama resists pressure to intervene militarily unless U.S. interests are at risk or Americans are threatened, placing his emphasis instead on training and supporting foreign governments or entities to tackle their own problems. But Clinton is more aggressive in her approach, believing the United States can and should play a more muscular role in the world.

“You know, when you’re down on yourself, and when you are hunkering down and pulling back, you’re not going to make any better decisions than when you were aggressively, belligerently putting yourself forward,” Clinton told Goldberg.

P.J. Crowley, a former State Department spokesman under Clinton, said she and the president share the same goals on some foreign policy issues but have different perspectives on how to achieve them.

“Her instinct is that while we do need to be mindful in deploying American power prudently, there’s a point when you’re being too cautious,” Crowley said. “She believes we’ve reached the point where we’re leaning a bit back instead of moving forward.”

Obama and Clinton agreed on some issues, including resetting U.S. relations with Russia and pivoting to Asia. But in other areas, they parted ways. Clinton wanted to send more troops to Afghanistan, leave a residual military force in Iraq and wait longer before withdrawing support for Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak during massive protests in Cairo.

In her interview in The Atlantic, she talks of halting, not just curbing, Iran’s nuclear program and more forcefully defending Israel’s actions against Hamas. And she would have supplied arms to the rebels in Syria, which she said “left a big vacuum, which the jihadists have now filled.”

In an interview with New York Times columnist Thomas L. Friedman, Obama said the idea that arming the rebels would have made a difference has “always been a fantasy.”

AFP Photo/Patrick Smith