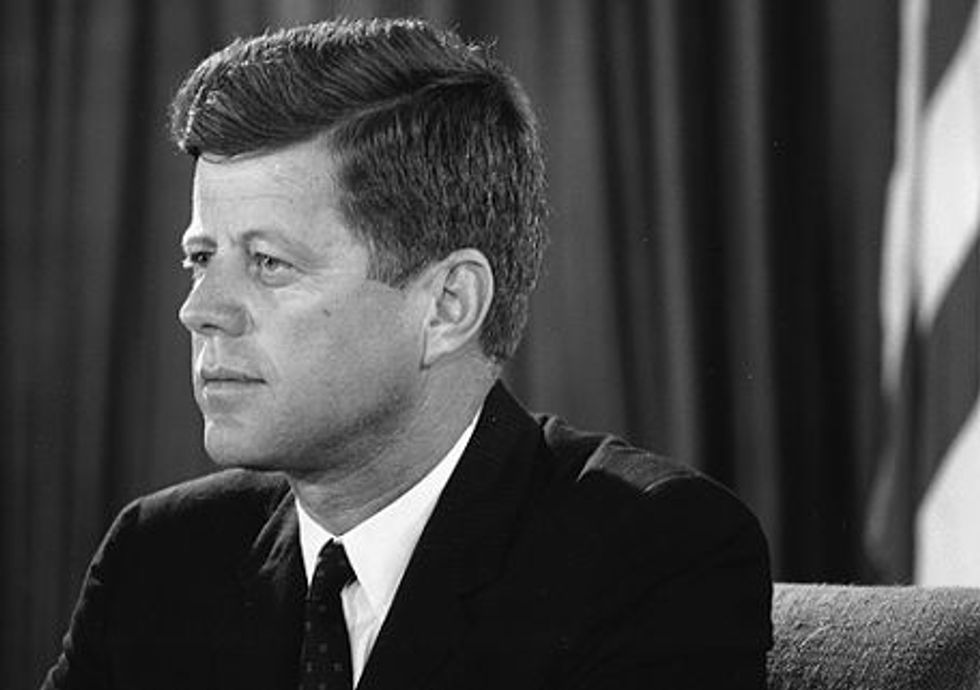

Looking back through the haze of history, it’s hard to see clearly a time when an American president would be driven through the streets of a U.S. city in an open convertible, wind swirling through his hair, as President John Kennedy was on that fateful day in Dallas 50 years ago. Yet, that picture emerges from the latter part of the 20th century, the not-so-distant past.

It was hardly a more innocent time. I won’t indulge in that cheap sentimentality. Black Americans were still subject to the harsh lash of Jim Crow; many women were at the mercy of violent husbands; pedophiles in high places preyed on their victims without fear of penalty.

Still, November 1963 was, in many ways, a more naive era — one before gun violence became an emblem of American life, before security trappings took over public and private buildings, before ubiquitous surveillance cameras, before the vicious hatred of alienated men (and a few women) strafed our public commons.

John Kennedy wasn’t the first American president to be assassinated, of course. He wasn’t commander in chief during a violent revolt, when the very fate of the republic hung in the balance. He wasn’t even the sitting president during the tumult of the latter 1960s, when the craziness of an unnecessary war and the continuing protests of a long-suffering people seemed the catalysts that might spark genuine revolution.

But Kennedy’s assassination 50 years ago did mark the opening of that apocalyptic period, that combustible era when a great man could be gunned down on a hotel balcony or in the passageway of a hotel kitchen. And it marked the end of something else, too — some quaint notion of security, of comity, of patriotism.

How stunned we all were at the news that spread surprisingly quickly for an age before Twitter, Facebook and 24-hour cable news. Few moments could so convulse a nation and unite it in grief. Some of my elementary school classmates cried at the news of the president’s death.

I remember it as the first in a series of bleak, unspeakable moments, incomprehensible atrocities that later consumed Martin Luther King Jr. and, in rapid succession, Bobby Kennedy. When President Kennedy was shot, the bloodshed was only just beginning.

The era’s violence took many others whose only crime was trying to form a more perfect union, from stalwart activists such as Medgar Evers to protesting students at Kent State and Jackson State. For all our complaints about the current state of our politics, awash in vitriol, this is a stable and predictable period compared to that.

Perhaps that’s because the America we created in the aftermath of the Era of Political Assassinations is a better one, a nation that President Kennedy might little recognize but greatly respect. Successive movements for full equality have advanced human rights for black and brown citizens, for women, for gays and lesbians. Kennedy’s daughter, Caroline, is now U. S. ambassador to Japan; she’s been elevated to the sort of significant political role few women held during his lifetime.

Communism, the scourge of Kennedy’s presidency, has collapsed. As a result, American presidents, Democratic and Republican, have had the luxury of attempting to scale back the world’s arsenal of nuclear weapons. With no significant military rival, the United States has stood astride the globe as a lone superpower.

Perhaps the change that would stun Kennedy most would be the complexion of the current occupant of the Oval Office, Barack Obama. His election represents not only the dramatic success of the civil rights movement, but also the demographic change largely ushered in by Kennedy’s brother, the late Senator Ted Kennedy. The senator championed legislation that allowed immigrants from across the globe, not just Western Europe, to enter the country.

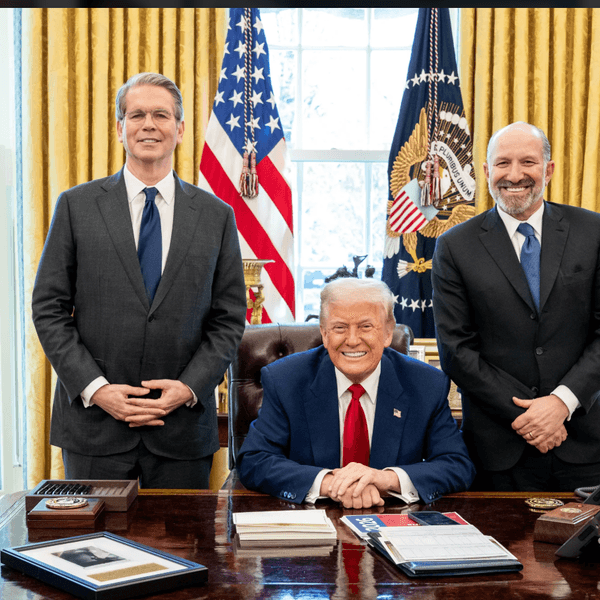

History and an American thirst for equality have helped to create a post-Kennedy nation of even greater promise than Camelot held. But it’s also a nation of less institutional trust, more paranoia, less civility. The current president takes to the streets in a motorcade that’s a rolling war machine.

We’ve gained much, but we’ve lost something, too.

(Cynthia Tucker, winner of the 2007 Pulitzer Prize for commentary, is a visiting professor at the University of Georgia. She can be reached at cynthia@cynthiatucker.com.)