Reprinted with permission from Uexpress.

History, despite its wrenching pain, cannot be unlived, but if faced with courage, need not be lived again. — Maya Angelou

On July 5, 1933, Elizabeth Lawrence, a black schoolteacher, was lynched in Jefferson County (Birmingham), Alabama. A mob of white men dragged her from her home, burning the house down as they left, because she had scolded a group of white schoolchildren for throwing rocks at her earlier in the day. When her son protested to authorities, he was threatened by the same mob and forced to flee to Boston.

If you didn’t know the story of Lawrence’s murder, that’s no surprise. Neither did I. America’s ignominious history of violent repression of its citizens of color is largely forgotten and occasionally denied.

That is certainly true of the sordid and miserable era of racial terror that rained down on black Americans — mostly, but not exclusively, in the Southern states — from the post-Civil War years through the middle of the 20th century, with lynching as a primary tool to reinforce fear and submission throughout the black community. America’s history of terrorist lynchings is very rarely acknowledged.

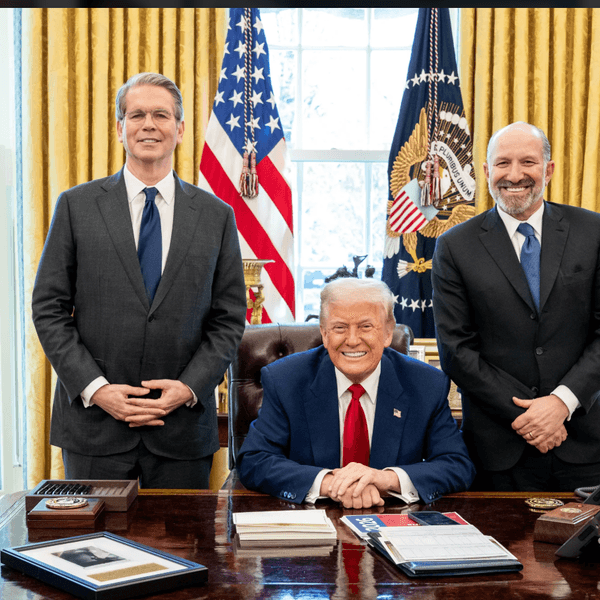

Bryan Stevenson, the “Genius Grant”-winning public interest lawyer best known for representing death penalty defendants, is determined to change that. With private funds, he and the staff of the Equal Justice Initiative, the Montgomery-based nonprofit he founded, have built a powerful, must-see memorial to victims of lynching, as well as an accompanying museum that draws a straight line from slavery to our current era of mass incarceration.

The National Memorial to Peace and Justice, which remembers the victims of lynchings, sits on a prominent Montgomery hilltop, from which visitors can see the Alabama River that served to ferry enslaved men, women and children throughout the interior of the South. (The museum and memorial had their official opening on Thursday, April 26.) The Legacy Museum occupies a building once used as a warehouse for the enslaved.

Having spent decades defending the poor who have been shabbily treated by a criminal justice system that claims to be impartial, Stevenson now believes that equal justice for all will be possible only when the nation fully acknowledges its brutal past.

“We haven’t addressed the legacy of slavery and the history of racial inequality in the way that we need to,” he told journalists recently. “I am persuaded that we are not free yet in America. We are burdened by this history. It’s created a kind of smog that’s in the air, and we all breathe it in. If we are going to get to freedom, we have to talk about these things.”

Stevenson and his staff spent years doing meticulous research to document more than 4,400 terror lynchings of black Americans across 20 states from 1877 to 1950. That’s more than any other group of researchers has uncovered, but Stevenson’s team was careful to include only those murders that were corroborated by at least two documents. (As Stevenson acknowledges, there were likely many more lynchings lost to history.)

The memorial and museum bring historical context to the bias and brutality that stalk the criminal justice system to this day and fuel black Americans’ troubled relationship with it. While popular culture tends to treat lynchings as mob justice of the sort you might see in a Western, they were, in fact, terrorism — murders meant to punish those who had offended social norms (as, apparently, Elizabeth Lawrence had), campaigned for equal rights or, perhaps, perpetrated a petty offense.

Lynchings were not merely extralegal; they were often committed with the cooperation of local law enforcement authorities, including sheriffs and judges. Contemporaneous newspaper clippings show that some of them were announced in advance. Horrifyingly, white citizens often treated lynchings as entertaining social events, packing picnic lunches and bringing their children to watch, even though human bodies might be burned and dismembered. As Stevenson notes, that savagery created a legacy in which many whites continue to believe that black bodies may be abused with impunity. The dehumanization of black people, Stevenson argues persuasively, has paved the road to mass incarceration.

This, of course, is not an easy history to discuss. Even some black Americans would rather not be reminded of a not-too-distant past in which our ancestors were treated as subhuman, not only denied basic liberties, but also beaten, tortured, murdered, dismembered. But I believe Stevenson is right: The only hope for overcoming that history is to acknowledge it, and the only way forward is to start with the truth.

Header image source.