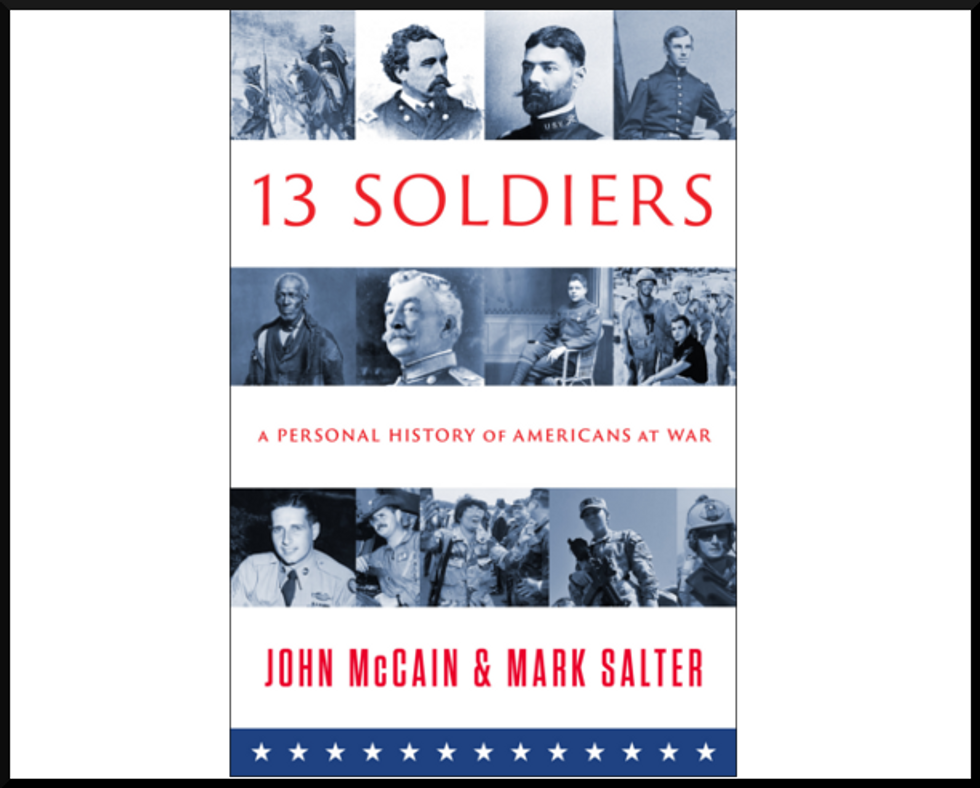

Weekend Reader: ‘Thirteen Soldiers: A Personal History Of Americans At War’

Senator John McCain and Mark Salter examine war as it was lived, fought, and endured on the ground in their new book, Thirteen Soldiers: A Personal History of Americans at War. Recounting the experiences of thirteen specific American soldiers, from 1776 to the campaigns of the 21st century, McCain and Salter consider the changing face of warfare and the qualities of duty and valor endemic to the armed forces in every military engagement from the Revolution to the present day.

McCain and Salter’s book is written with thrilling immediacy, insight, and reverence for the men and women who have risked and sacrificed their lives for their country. Much more than a military history, Thirteen Soldiers brings famous battles and campaigns down to the individual scale, enhances our understanding of the costs and consequences of battle, and introduces a human dimension to the history of armed conflict.

In the following excerpt from the book’s thirteenth and final chapter, Private Monica Brown, a frontline medic, is injured when her convoy traveling through rural Afghanistan is ambushed.

You can purchase the book here.

Private Monica Brown reported to the hospital at Forward Operating Base Salerno in Khost Province, Afghanistan, on February 7, 2007. Salerno is situated on three hundred flat acres in the shadow of the jagged mountain peaks along Afghanistan’s border with Pakistan. In 2007 it was one of the biggest and oldest FOBs in Afghanistan, a small city of canvas and plywood with a population of three thousand, and a major hub of coalition operations. It had an airstrip, helo pads, airplane hangers, well-staffed medical facilities, a big chow tent, decent food in ample quantities, a good-sized, well-equipped gymnasium, a PX, a chapel, a movie theater (with a large-screen TV and DVD player), a café, and a restored mosque. Taliban and al Qaeda attacked it so often with rockets and mortars its harassed inhabitants nicknamed it “Rocket City.” A few days before Brown arrived there, a suicide bomber had killed himself and a dozen others at Salerno’s front gate.

Brown helped medical staff treat trauma patients, both soldiers and local civilians. The first patient she worked on was a local male with a gunshot wound. “That’s when the switch flipped,” she recalled, “and … everything changed over from training to me really liking the job.”

In March she was temporarily detailed to an isolated outpost with the 4th Squadron, 73rd Cavalry Regiment in rugged, volatile Paktika Province. The squadron needed a female medic to provide basic medical care to Afghan women in the villages they patrolled. Female medics and corpsmen were often temporarily assigned to combat units to treat Afghans in their homes or in clinics the army set up to help build local relationships crucial to a successful counterinsurgency. Male medical personnel aren’t permitted to examine Afghan women in the extremely patriarchal society, especially in the remote, poorest locations where the Taliban is strongest. Female soldiers often helped in home searches and interrogations too. They shared the same risks and hardships male soldiers faced on the missions, the same threat of ambush, the same threat of death or injury from enemy fire or IEDs. They ate the same food, slept on the same stony ground, felt the same fears.

Brown arrived in the advent of spring, when the snow was starting to melt in the Toba Kakar Mountains, the apricot trees were beginning to bloom, and the Taliban were launching another offensive. It was a dangerous place to be, and it got more dangerous every day Brown was there. Taliban and Haqqani network fighters are plentiful there. Paktika’s rugged terrain offers abundant hiding places and hard-to-detect routes into the country from Pakistan. One of the important tribes in the province, the Sulaimankhel, was hostile and a reliable source of recruits for the Haqqani. Suicide bombings were common.

Living conditions in the outpost were pretty primitive. Soldiers were crowded together in tents behind Hesco barriers—wire mesh containers filled with dirt that served as the walls of the command observation post. They were without power or running water. They ate MREs (meals ready to eat) or local dishes Afghan soldiers and interpreters sometimes provided. The aid tent where Brown worked was only forty square feet. And she was the only woman there. She loved it, she told the Washington Post.

Brown wasn’t there very long when she started going on patrols as a line medic with Delta and Charlie troops. That wasn’t in her job description or consistent with official policy, but nobody bothered about that, not out there. Medics were in scarce supply at the outpost, and as someone in Charlie Troop commented afterward, she was one of the best there. They went looking for Taliban, weapons caches, and bomb makers for three, four, and five days at a time, returned for a day’s rest and resupply, and went back out again. She loved that too, hunting bad guys, sleeping under the stars. She carried her own weight, she later insisted to the 60 Minutes reporter Lara Logan. “I expected to be treated like one of the guys. So, that’s how I got treated.”

She hadn’t run into any serious trouble yet. No IEDs, no ambushes, no firefights. She had been on patrol almost constantly for several weeks, and she still did not know for certain if she could do the job. She had not had to keep someone alive while someone else was trying to kill her.

On the afternoon of April 25, 2007, she had been out two days on a patrol with 2nd Platoon from Charlie Troop. The platoon’s medic had gone on leave, and Brown was the best of the available replacements. They had received a tip there might be a couple members of a bomb-making cell and some weapons in a little village in the Jani Khel district. It would be their last stop of the day before spending the night at an Afghan National Army camp. They searched a dry well before entering the village and searching a few homes. If there were Taliban there they had been warned in advance and made their escape. The streets were empty, but the Afghans they encountered in their homes were noticeably hostile. Their welcome worn out the moment they appeared, the soldiers were as happy to vacate the area as its inhabitants were to see them leave.

They traveled in a column of four up-armored Humvees and an Afghan Army Ford pickup truck. Approximately a hundred meters separated each vehicle from the next, a distance considered prudent in hostile country, where, in the words of the army manual for convoy tactics, you want “to reduce the number of vehicles in the kill zone,” in the event you are attacked or drive over a mine. As the sun started to set, the convoy took another precaution a couple of miles outside the village: they pulled off the road into an adjacent wadi, a dry riverbed. As a general rule, you are less likely to encounter an IED if you drive off-road. The Taliban believe ours is a road-bound army. They are right for the most part, and it is a liability in the asymmetrical wars the army has fought this century. But soldiers adjust their tactics to the threat, and when a wadi or open field can get them to where they need to be, they’ll take it.

The platoon commander, Lieutenant Martin Robbins, was in the lead Humvee. Staff Sergeant Aaron Best was Robbins’s gunner. Brown was in the third Humvee with platoon sergeant Jose Santos. A hundred meters behind her, in the last Humvee, were Sergeant Zachary Tellier and specialists Jack Bodani, Stanson Smith, and Larry Spray. The first three Humvees and the pickup had turned into the wadi and were rolling. The last Humvee started to ease over the bank when its left rear tire struck a pressure-plate mine. The explosion nearly blew a man out of the gun turret. It ignited the fuel tank and the extra fuel cans stored in the rear, creating a fireball that engulfed the Humvee. All four men inside were wounded.

If you enjoyed this excerpt, purchase the full book here.

Excerpt from Thirteen Soldiers: A Personal History of Americans at War by John McCain and Mark Salter. Copyright © 2014 John McCain and Mark Salter. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Want more updates on great books? Sign up for our daily email newsletter here!