By Kelly Smith, Minneapolis Star Tribune

MINNEAPOLIS — On a quiet Saturday evening in 1989, a police officer was called to a Maple Grove house on a routine report of a teen runaway. He interviewed the parents. And the report was filed, drawing little police, public, or media attention.

Now, 25 years later, dozens of FBI investigators, state forensic scientists, and police officers are intensifying work on an unsolved mystery: What happened to Amy Sue Pagnac?

The 13-year-old, who vanished after a trip to her family’s central Minnesota farm, would now be 38, and her birthday this month was a reminder to her family and classmates of a case they say never got the attention it deserved — until now.

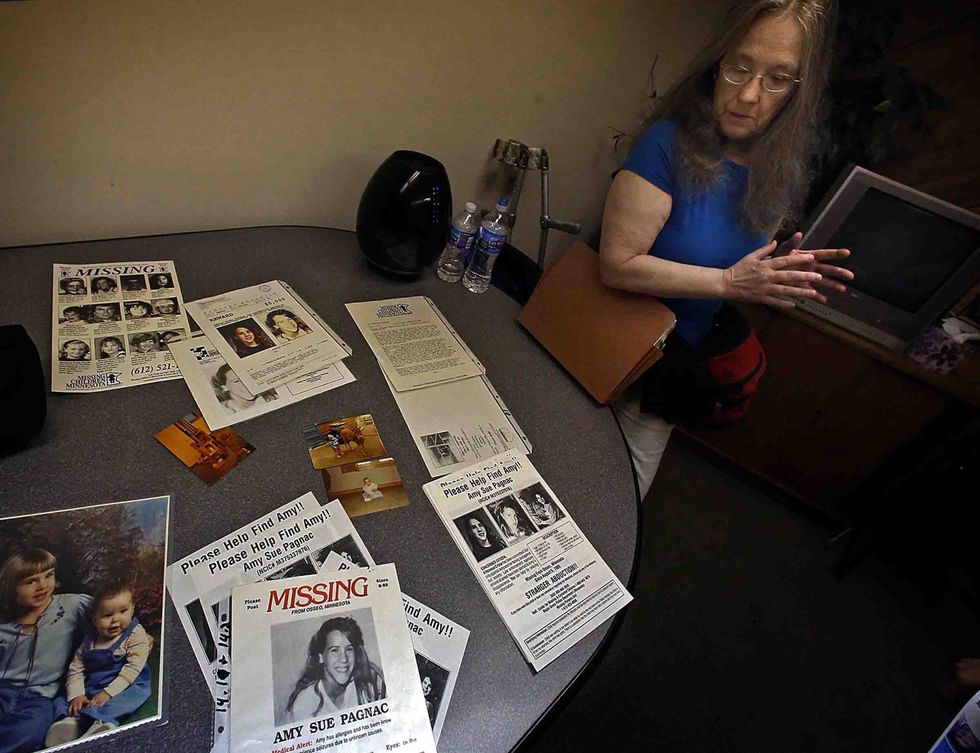

“It’s another year where she’s not present,” her mother, Susan Pagnac, said Friday while going through Amy’s childhood photos. “You focus on all the good memories — that’s all you have left.”

Two months after Amy disappeared, 11-year-old Jacob Wetterling was abducted by a masked gunman in St. Joseph, Minn., sparking national media coverage and drawing thousands of people to community searches. Jacob became the face of missing children in Minnesota and nationwide, and the search for him, which continues to this day, changed the way Americans look at missing-children cases.

But Amy’s case, without a suspect or evidence of a crime, was filed away quietly. When classmates started eighth grade, they found out she was gone when her smiling face showed up on their milk cartons. Years later, Amy wasn’t even mentioned at their 1994 high school commencement.

Now, the case is getting renewed interest statewide. On May 18, about 40 officers showed up at the family’s Maple Grove home with a sealed search warrant, conducting a six-day search and tearing up the backyard patio. On June 2 they did a four-day dig at the family’s wooded 140-acre Isanti County farm.

Police won’t say what prompted the searches or whether anything was found. No suspects have been named.

___

At 5:45 p.m. on Aug. 5, 1989, young police officer Jeff Garland was called to a two-story green house with purple siding in the 9700 block of Hemlock Lane N. It was a rather routine call for a juvenile runaway — a call police had responded to there several times that summer. Garland said Amy’s parents were frustrated with her running away repeatedly, suspecting she was wandering off to have sex or drink alcohol.

“They were upset with Amy, with her behavior; they thought she was promiscuous,” said Garland, now retired. “They didn’t know how to control her behavior … no different from a typical parent with a teenager.”

Susan Pagnac disputes that, saying that there was no family argument and nothing unusual about Amy’s behavior except for having a headache.

Pagnac’s husband, Marshall Midden, told police he and Amy went to tend crops at the farm at noon. The whole family was supposed to go, Pagnac said, but Amy’s sister had an event that day that she and her mother were supposed to attend. Midden and Amy were returning home about 5 p.m. when he stopped at an Osseo gas station 2 miles away. After he used the bathroom, he came outside to find the car empty, he said.

In a copy of the original police report, the couple told Garland that Amy had a cerebral medical problem that put pressure on the brain, creating headaches that caused her to wander off. Pagnac said recently that Amy had seizures and may have been bipolar, but she hadn’t been medically diagnosed or treated yet.

Police had responded to the house for several runaway reports that summer, according to a record of 65 calls to the address in the past 30 years. In the summer of 1989, police responded to a juvenile runaway report May 2. Then on June 28, there was a reported domestic assault, which Pagnac said was Amy having a seizure and accidentally flailing her arm up at her mother. Two juvenile runaway calls were reported June 29 followed by another the next day.

About a month later, Amy vanished.

Details about the calls may never be disclosed; the city said records not linked to the active investigation were purged in 1999, part of the city’s records retention policy.

Midden and Pagnac have clean criminal records.

Photo: Jim Gehrz/Minneapolis Star Tribune via MCT