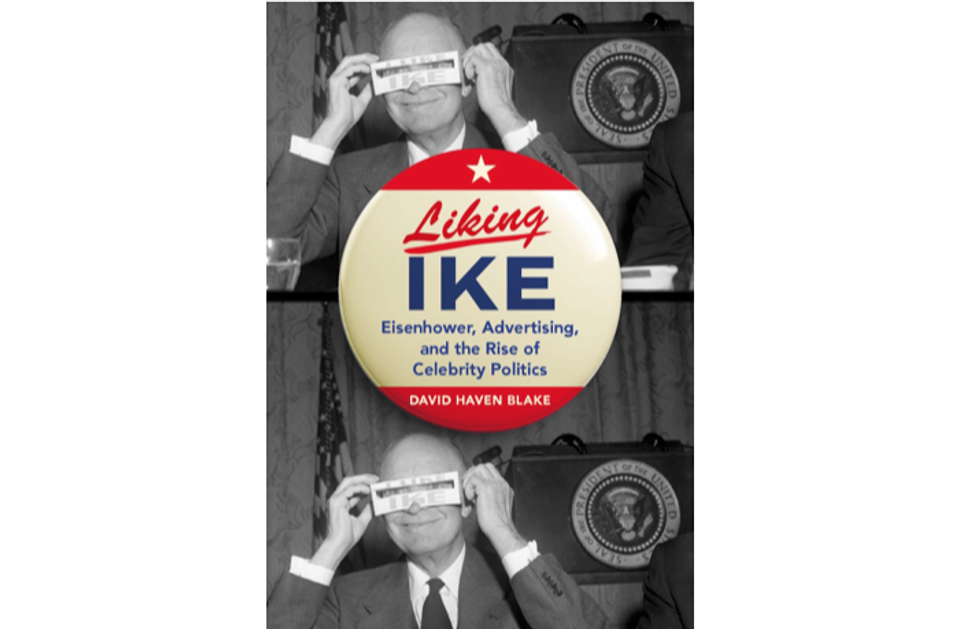

EXCERPT: ‘Liking Ike: Eisenhower, Advertising, and The Rise of Celebrity Politics’

A reality star is now a major party presidential candidate, but it turns out, celebrity politics are not a new thing.

In Liking Ike, author David Haven Blake explores the crucial and often overlooked role that celebrities and advertising agencies had in Dwight Eisenhower’s presidency. Even by today’s standards, many Americans will be surprised to learn that celebrities of the time were a constant presence in political strategies, and particularly in Eisenhower’s campaigns.

Using original interviews and archival material, Blake explains how Madison Avenue executives used celebrities as tools in politics as the age of Television began.

You may read an excerpt below, and you can purchase the book here.

__

In March of 2010, Frank Gehry unveiled his new plans for the Dwight D. Eisenhower Memorial across from the National Mall in Washington, DC. A bipartisan public commission had selected Gehry, one of the world’s most acclaimed architects, to memorialize the man who led the Allied Forces during World War II and then became the thirty-fourth president of the United States. From the outset, the commission sought a design that would both honor Eisenhower and “inspire generations with his devotion to public service, leadership, integrity, [and] life-long work ethic.” It was equally important, the commission stated, that the design reflect Eisenhower’s “total devotion to the values and processes of democracy,” the implication being that, of all his accomplishments, perhaps the greatest was his respect for the grassroots participation that makes up a democratic society.

Some memorials are made to commemorate, others to tell a story. Gehry’s proposal ignited controversy when the Eisenhower family publicly objected to the “romantic Horatio Alger notion” at the heart of his design. Although he would revise his plans multiple times, Gehry held fast to a narrative depiction of Ike’s life. In contrast to Abraham Lincoln and Thomas Jefferson, who heroically tower over the visitors to their memorials, Eisenhower appears in the most recent design as a young man sitting on a stone ledge with an image of the Kansas prairie behind him. From this informal perch, he looks upon two massive stone blocks, each one the backdrop for a sculpted scene from his adult life. In one, he is a general talking to troops before D-Day; in the other, he stands symbolically between representatives of the military and civilian needs of the country. From the beginning, the project design called for a digital component (called the E-Memorial) that would feature multiple images and video of Eisenhower and his times: cadets doing mathematics on a West Point blackboard, soldiers walking through the French countryside, the president waving to the crowds from a Cadillac El Dorado after his 1953 inauguration ceremony. With the aid of wireless electronics, these images would trace how this modest young man rose from the heartland to have an enormous impact on the twentieth century.

Among the ancillary images included in the E-memorial, a worthy addition would be an image of Eisenhower surrounded by celebrities. The designers could depict Eisenhower and a group of stars singing around a piano during the 1952 presidential campaign or Eisenhower’s filmed appearance on the Colgate Comedy Hour to kick off 1955’s Armed Forces Week. Then there is Eisenhower in white tie, grinning with Bob Hope, Jane Powell, and Pearl Bailey, or Eisenhower laughing with Arnold Palmer on the grounds of Augusta National Golf Club. In no way, of course, should these images rival the attention given to Eisenhower’s great achievements: the victory over European fascism, the peace in Korea, the booming postwar economy. However Eisenhower and his stars deserve their own commemorative treatment. Though the commission or his family might not agree, the images are as much a part of Eisenhower’s presidency as they are of the scrapbooks of these departed celebrities. As this book explains, they go hand-in-hand with Eisenhower’s commitment to the values and processes of democracy. They, too, should be engraved in our cultural memory.

To many, Dwight Eisenhower would be a surprising, even shocking, addition to the pantheon of celebrity-infused presidents and political campaigns. A humble plainsman, a soldier-citizen, a steadfast and grandfatherly head of state, he seems worlds away from such Hollywood-tinged presidents as John F. Kennedy, Ronald Reagan, and Bill Clinton. When we see Ike’s grainy black-and-white image reviewing American troops in London, when we recall his warnings about the military-industrial complex, we are inclined to see a model of integrity and foresight rather than theatrical charm. And yet, no matter how durable his accomplishments, no matter how penetrating his vision, Eisenhower gave celebrities a curious role in promoting him as a political candidate. Guided by television pioneers and Madison Avenue advertising executives whom insiders dubbed “Mad Men,” he cultivated scores of famous supporters as a way of building the kind of broad-based support that had eluded Republicans for twenty years.

Eisenhower’s presidential campaigns were so saturated with stardom that they would astonish many Americans today. Broadway stars performed at jam-packed Madison Square Garden rallies designed to drum up enthusiasm for his candidacy. Roy Disney created an animated television commercial, and Irving Berlin composed a campaign theme song, turning the phrase “I Like Ike” into the most memorable political slogan in American history. Popular figures from the world of sports appeared at fundraising dinners and in television commercials touting Eisenhower’s record. Working with Madison Avenue executives, actors and actresses gave press conferences extolling the benefits of an Eisenhower presidency. Critics complained that all the advertisements and endorsements risked turning Eisenhower into a commodity, as if he were a carton of Lucky Strike cigarettes being plugged by comedian Jack Benny. Far from objecting, Ike’s advisers invited such comparisons. As they described it, their job was to merchandise the man who was at once their client, their product, and their candidate. Television advertising, they explained, simply extended the reach of democracy.

During the same period, Eisenhower himself was developing into a congenial, media-savvy performer. Initially flustered by the tedium and distractions of being on camera, he grew to understand the demands of the presidency in the television age. He worked with Robert Montgomery, the former president of the Screen Actors Guild and the popular host of an eponymous hour-long drama series on NBC, to help improve his televised interviews and speeches. As producers, directors, and cameramen were figuring out how to maneuver their heavy equipment through the White House windows and hallways, Montgomery was teaching the president how to read from a teleprompter and appear more open and engaging. From his office in the West Wing, he developed camera angles and poses that would help Eisenhower seem youthful, invigorated, and authoritative on TV. Although he had been famous for well over a decade and had hired advisers to improve his communication skills, it was television that transformed Ike into a media celebrity. The Academy of Television Arts and Sciences awarded the president an honorary Emmy for his innovative use of the medium to communicate with the American people.

Liking Ike tells the story of how Eisenhower’s celebrity politics was developed on Madison Avenue, practiced in the White House, debated in the press, protested by his opponents, and then remade by subsequent generations of politicians and stars. It analyzes the ways that this most respected of leaders, a hero throughout much of the world, was drawn into the conflux of television, advertising, and political glamour that emerged in the 1950s. Not willing to stand purely on his credentials, Eisenhower agreed to the same set of promotional strategies that advertisers used to sell products like laundry detergent and shaving cream. Although they may seem obvious to us now, the systematic efforts to decorate a candidate with stardust were then perceived as being radically new, and the glitz surrounding Eisenhower’s campaigns aroused consternation and concern. To some at the time, the image-making seemed more appropriate for a movie star or talk show host than the Supreme Commander of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). “Get rid of the vaudeville, pretty-girl” embroidery, one editorialist advised, “and conduct the campaign on a level commensurate with the General’s intelligence and position.” But to leading Republicans and the advertising executives they hired, television made the power of celebrity endorsements appealing, and they were confident that this softer, glamorized version of politics would attract votes. The result was a vision of American politics in which publicity would become a principal site of democracy and voters would soon identify themselves as both an electorate and an audience. The rise of Eisenhower’s “star strategy” made for an odd historical juxtaposition. At the same time that Congress was investigating the influence of Communists in Hollywood and the film and broadcasting industries were blacklisting alleged subversives, advertising executives were seeking ways to bring conservative performers into the political spotlight. The irony did not trouble the advertising agencies that worked on Ike’s campaigns, for as they saw it, their task was not to politicize entertainment but to make politics more entertaining.

Reprinted from “Liking Ike: Eisenhower, Advertising, and The Rise of Celebrity Politics” by David Haven Blake with permission from Oxford University Press. © Oxford University Press 2016.

If you enjoyed this excerpt, purchase the full book here.

Want more updates on great books? Sign up for our daily email newsletter here.