To Protect Our Privacy, Make The FISA Court Act Like A Real Court

By Faiza Patel and Elizabeth Goitein, Los Angeles Times (TNS)

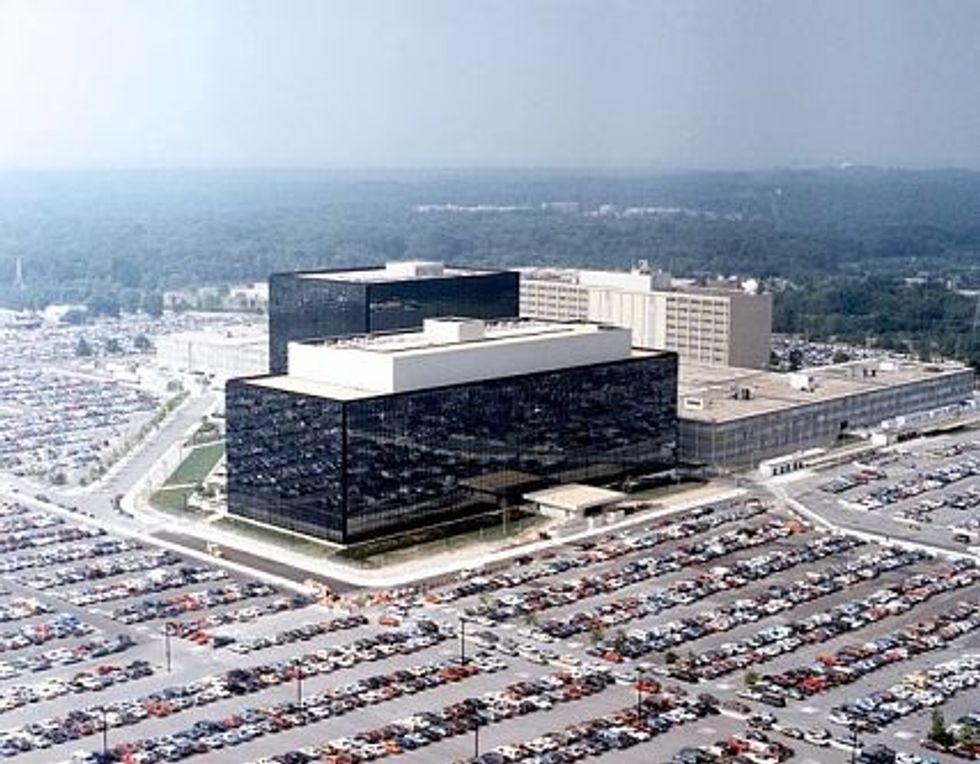

The expiration of key surveillance authorities this spring will force Congress to grapple with the sprawling spying activities exposed by Edward Snowden. Defenders of the status quo sound a familiar refrain: The National Security Agency’s programs are lawful and already subject to robust oversight. After all, they have been blessed not just by Congress but by the judges of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court, or FISA court.

When it comes to the NSA’s mass surveillance programs, however, the FISA court is not acting like a court at all. Originally created to provide a check on the executive branch, the court today behaves more like an adjunct to the intelligence establishment, giving its blanket blessing to mammoth covert programs. The court’s changed role undermines its constitutional underpinnings and raises questions about its ability to exercise meaningful oversight.

The FISA court was born of the spying scandals of the 1970s. After the Church Committee lifted the curtain on decades of abusive FBI and CIA spying on Americans, Congress enacted reforms, including the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978. The law established a special court to review government applications to intercept communications between Americans and foreigners overseas for the purpose of acquiring information about foreign threats.

Members of Congress debating the law were concerned about a court that would operate in secret and hear only the government’s side of the argument. The Constitution limits courts to resolving actual “cases or controversies.” This generally requires the presence of two parties with adverse interests, as well as a concrete dispute that allows the court to apply the law to the facts of the case.

Although even the Justice Department agreed it was a “difficult question,” Congress decided that the FISA court procedure was constitutional because of its similarity to regular criminal warrants. There, too, the court hears only from the government, yet constitutional requirements are satisfied because the subject of the search eventually must be notified and may mount a challenge at trial. (The analogy is imperfect, as subjects of FISA surveillance are notified only if legal proceedings result, which is rare in foreign intelligence cases.) And, like their counterparts reviewing criminal warrant applications, FISA judges would apply the law to the facts of a particular case.

Nearly four decades later, the core assumptions about what made the FISA court legal have been upended. Take the court’s role in approving the NSA’s bulk collection of Americans’ phone records. The Patriot Act allows the FBI to obtain business records if it demonstrates to the FISA court that they are “relevant” to a foreign intelligence investigation. As Snowden revealed, the FISA court accepted the government’s argument that all Americans’ records are “relevant” because some relevant records are buried within them. It allowed the NSA to create a massive database of highly personal information without any individualized offer of proof.

A similar abandonment of case-by-case adjudication resulted from the FISA Amendments Act of 2008. These amendments removed the law’s requirement that the government obtain an order from the FISA court each time it collects communications between a foreign target and an American.

Today, when collecting such communications, the government need only implement procedures to ensure the program adheres to broad statutory requirements. The FISA court’s role is limited to approving these procedures; it has no role in judging how the government applies them in individual cases. Given the explosion in global communications, this means that millions of Americans’ phone calls, emails and text messages are collected by the NSA, no individualized court order required.

These judicial activities look nothing like the granting of warrants in criminal investigations. Judges in criminal cases do not issue orders allowing police officers to search any and all houses, on the ground that some surely contain evidence of a crime. Nor do judges secretly approve general guidelines for searching homes, leaving the application of them to the discretion of police officers.

There are good reasons the Constitution charges courts with adjudicating disputes between parties rather than pre-approving broad government programs. It preserves the separate functions of the branches of governments. And it ensures that courts do not take on a role that they are ill-equipped to handle. Time and again, as the Snowden archives reveal, the FISA court was blindsided by how the NSA actually implemented the vast programs the court approved.

Lawmakers have introduced bills to require greater disclosure of FISA court decisions and to establish a public advocate to argue against the government in some cases. Though helpful, these measures would not fully address the fundamental problem: The FISA court simply does not act like a court anymore.

Congress can fix this when it tackles surveillance legislation. Judicial approval should be required each time the executive branch seeks to acquire an American’s business records or communications with a foreign target. Challenging surveillance after the fact should be made easier too. That would require more robust disclosure and a dismantling of the jurisdictional barriers that stymie legal challenges to surveillance.

By shoring up the court’s role as an independent check on the executive branch, these reforms will better safeguard Americans’ privacy and prevent abuse. That was Congress’ original purpose in creating the FISA court. After decades of drift, it’s time to return the court to its constitutional moorings.

Faiza Patel and Elizabeth Goitein are authors of What Went Wrong With the FISA Court and directors of the Liberty and National Security program at the Brennan Center for Justice. They wrote this for the Los Angeles Times.

Photo: Penn State via Flickr